Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-12-09 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14462 Mark A. K. Gillespie, Stein Joar Hegland

|

1 INTRODUCTION

In response to recent climate change, many plants have altered the timing of life-history stages (phenology), with events such as budburst, flowering and fruiting occurring much earlier than pre-industrial records (CaraDonna et al., 2014; Parmesan, 2006). Although the magnitude and direction of responses may be species specific (CaraDonna et al., 2014; Collins et al., 2021), the overwhelming pattern is cause for concern due to the unprecedented rate at which organisms at all trophic levels are changing. Differential responses may lead to asynchrony between interacting species (Both et al., 2009; Burkle et al., 2013; Hegland et al., 2009), and more research is required to enhance our understanding of the demographic impacts, such as those on reproductive success (CaraDonna et al., 2014; Forrest & Miller-Rushing, 2010; Iler et al., 2021). Furthermore, while phenological changes are typically linked in studies to bottom-up factors, such as genetics or climatic cues (Forrest & Miller-Rushing, 2010), plant vegetative and flowering phenology can be advanced or delayed by top-down stressors such as herbivory (Poveda et al., 2003; Tadey, 2020; Zhu et al., 2016). As increased herbivory and more frequent insect outbreaks have been hypothesised as consequences of a warming world (Hamann et al., 2021; Tylianakis et al., 2008), more experimental studies are needed to explore the combined effects of abiotic and biotic stressors.

Typically, research focusses on well-established climatic cues of phenological change. The accumulation of heat (e.g. degree days) is well documented as a predictor of flowering (Jackson, 1966; Miller-Rushing et al., 2007), and many temperate plants also have a winter chilling requirement that restricts emergence to springtime (Morin et al., 2009). In alpine conditions and at high latitudes, snow cover and snow melt dates provide important abiotic controls to winter survival and emergence phenology (CaraDonna et al., 2014; Iler et al., 2013). By contrast, herbivory is often considered to impact plant performance directly by reducing biomass, removing photosynthetic and/or reproductive tissue and negatively affecting fitness (Barrio et al., 2017; Bustos-Segura et al., 2021; Moreira et al., 2019; Rasmussen & Yang, 2023), although compensatory responses are also common (e.g. Lemoine et al., 2017; Poveda et al., 2003). However, additional impacts of herbivory also occur when plants under attack redirect resources from growth and reproduction to defence in an effort to improve herbivory ‘resistance’ (Benevenuto et al., 2020), and the altered physiology can substantially change both vegetative and flowering phenology (Forkner, 2014; Freeman et al., 2003; Ru & Fortune, 1999; Young et al., 1994).

Despite the top-down role of herbivory on phenology, the exact mechanism is unclear. In some studies, herbivory is considered to have an indirect effect on phenology, via physical modifications to microclimate, community composition and interspecific competition (Han et al., 2016). For example, some species-specific delays to vegetative and flowering phenology under intense large herbivore grazing (Tadey, 2020) or in controlled grazing experiments (Han et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016), were attributed to the impact of large herbivore presence on soil moisture. Studies investigating the impact of herbivory by insects have identified more direct phenological impacts, such as shortening flowering duration (Poveda et al., 2003; Schat & Blossey, 2005), delayed flowering (Agrawal et al., 1999; Freeman et al., 2003; Lemoine et al., 2017) and advanced flowering due to resource allocation changes (Bustos-Segura et al., 2021; Pak et al., 2009). Others have used the organic compound methyl jasmonate (MeJA) to induce defence responses similar to those exhibited during insect herbivore attack and found that the enhanced herbivory resistance caused delayed (Agrawal et al., 1999; Zhai et al., 2015), advanced (Pak et al., 2009) and neutral (Thaler, 1999) phenological effects. These conflicting results have raised questions about the role of herbivory in phenology, particularly as they either failed to disentangle the impacts of large herbivore grazing on plant physiology, or are based on laboratory conditions, annual plants and laboratory-reared insects.

Few studies have explored the combined impact of bottom-up and top-down drivers, such as warming and herbivory, on plant phenology (Lemoine et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2023). With a lack of consensus on the impact of herbivory, combined effects may counterbalance each other in the case of an herbivory-induced delay and warming advance (Lemoine et al., 2017), or lead to additive effects with responses in the same direction (Sun et al., 2023). Similarly, species effects may depend on climatic context, such as elevation, with suboptimal and relatively stressful conditions exacerbating some responses (Gimenez-Benavides et al., 2011; Hegland & Gillespie, 2024). To address these uncertainties, we conducted the first study of combined warming and herbivory resistance effects on the phenology of two long-lived dwarf shrubs in field conditions, at three elevations in open boreal forests in Western Norway. We used MeJA to simulate plants' physiological resistance responses to a single year of insect outbreaks (top-down effect) and open top chambers (OTCs) to simulate continuous summer warming (bottom-up effect). We then followed two plant species that are responsive to both treatments in different ways depending on elevation and optimal growing conditions. Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry), an early-flowering deciduous species that thrives at mid-elevations in Norway (ca. 450 m.a.s.l.), shows typical induced defence responses to MeJA (reduced growth and herbivore damage; Benevenuto et al., 2020), although conflicting phenological responses to warming by OTCs have been reported (Anadon-Rosell et al., 2014; Prieto et al., 2009). The later-flowering and smaller evergreen shrub V. vitis-idaea (lingonberry), which is drought tolerant and performs well at low and warmer elevations, not only appears less responsive to induced defences (Hegland & Gillespie, 2024), but also advances phenology under artificial warming (Rosa et al., 2015). Of the two species, bilberry naturally tends to suffer more herbivore damage than lingonberry (e.g. Kozlov et al., 2015).

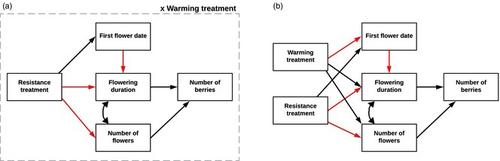

Using our combined treatments and study species, we aimed to quantify vegetative and reproductive phenological responses, and to establish consequences to plant fitness in the form of reproductive output. Our first research question was (1) What impact does the combined treatment of experimental warming and induced herbivory resistance have on vegetative and reproduction phenology in bilberry and lingonberry at three different elevations? Based on previous responses of these plants, we expected (a) advances under warming with the largest advances at higher altitudes where temperature is limiting, (b) delays due to induced resistance, with stronger responses in the year following MeJA application and (c) the combination of treatments would cancel each other out in the year after MeJA application, although warming at our highest alpine site may make plants more resistant to herbivory (Hegland & Gillespie, 2024). We also expected bilberry to be more responsive to treatments, as it is more susceptible to drought stress and insect outbreaks (Taulavuori et al., 2013). As the consequences of changing phenology to plant fitness and variables related to demography are rarely studied (Iler et al., 2021), we further posed the question (2) To what extent do shifts in phenology impact the reproductive output of bilberry and lingonberry? We answered this question with structural equation modelling and built our models on the assumption that alterations to phenology would negatively impact reproductive output due to mismatches with pollinators (Moreira et al., 2019; Schat & Blossey, 2005), but that the positive effect of warming on phenology and plant development would cancel these effects out (Lemoine et al., 2017).

中文翻译:

矮灌木的食草抗性与模拟变暖相结合,以改变物候并减少繁殖

1 引言

为了应对最近的气候变化,许多植物改变了生活史阶段(物候学)的时间,发芽、开花和结果等事件比工业化前的记录发生得早得多(CaraDonna et al., 2014;Parmesan, 2006)。尽管反应的大小和方向可能是物种特异性的(CaraDonna等人,2014 年;Collins et al., 2021),但由于所有营养级生物体的变化速度前所未有,这种压倒性的模式引起了人们的关注。不同的反应可能导致相互作用的物种之间的异步(Both et al., 2009;Burkle et al., 2013;Hegland et al., 2009),并且需要更多的研究来增强我们对人口影响的理解,例如对生殖成功的影响(CaraDonna et al., 2014;Forrest & Miller-Rushing, 2010;Iler et al., 2021)。此外,虽然物候变化在研究中通常与自下而上的因素有关,如遗传学或气候线索(Forrest & Miller-Rushing,2010),但植物营养和开花物候可能会因自上而下的压力因素如食草性而提前或延迟(Poveda等人,2003年;Tadey,2020 年;Zhu et al., 2016)。随着食草动物的增加和更频繁的昆虫爆发被假设为世界变暖的后果(Hamann 等人,2021 年;Tylianakis et al., 2008),需要更多的实验研究来探索非生物和生物压力源的综合影响。

Typically, research focusses on well-established climatic cues of phenological change. The accumulation of heat (e.g. degree days) is well documented as a predictor of flowering (Jackson, 1966; Miller-Rushing et al., 2007), and many temperate plants also have a winter chilling requirement that restricts emergence to springtime (Morin et al., 2009). In alpine conditions and at high latitudes, snow cover and snow melt dates provide important abiotic controls to winter survival and emergence phenology (CaraDonna et al., 2014; Iler et al., 2013). By contrast, herbivory is often considered to impact plant performance directly by reducing biomass, removing photosynthetic and/or reproductive tissue and negatively affecting fitness (Barrio et al., 2017; Bustos-Segura et al., 2021; Moreira et al., 2019; Rasmussen & Yang, 2023), although compensatory responses are also common (e.g. Lemoine et al., 2017; Poveda et al., 2003). However, additional impacts of herbivory also occur when plants under attack redirect resources from growth and reproduction to defence in an effort to improve herbivory ‘resistance’ (Benevenuto et al., 2020), and the altered physiology can substantially change both vegetative and flowering phenology (Forkner, 2014; Freeman et al., 2003; Ru & Fortune, 1999; Young et al., 1994).

尽管食草性在物候学中自上而下的作用,但确切的机制尚不清楚。在一些研究中,食草性被认为通过对小气候、群落组成和种间竞争的物理改变对物候产生间接影响(Han et al., 2016)。例如,在密集的大型食草动物放牧(Tadey,2020 年)或受控放牧实验(Han et al., 2016;Zhu et al., 2016) 归因于大型食草动物的存在对土壤水分的影响。调查昆虫食草影响的研究已经确定了更直接的物候影响,例如缩短开花时间(Poveda 等人,2003 年;Schat & Blossey,2005),延迟开花(Agrawal等人,1999;Freeman et al., 2003;Lemoine等人,2017 年)和由于资源分配变化而导致的提前开花(Bustos-Segura等人,2021 年;Pak et al., 2009)。其他人使用有机化合物茉莉酸甲酯 (MeJA) 来诱导类似于昆虫食草动物攻击期间表现出的防御反应,并发现增强的食草抵抗力导致延迟(Agrawal 等人,1999 年;Zhai et al., 2015)、高级 (Pak et al., 2009) 和中性 (Thaler, 1999) 物候效应。这些相互矛盾的结果引发了人们对食草动物在物候学中的作用的质疑,特别是因为它们要么未能理清大型食草动物放牧对植物生理学的影响,要么基于实验室条件、一年生植物和实验室饲养的昆虫。

很少有研究探讨自下而上和自上而下的驱动因素(如变暖和食草)对植物物候的综合影响(Lemoine et al., 2017;Sun等人,2023 年)。由于对食草活动的影响缺乏共识,在食草动物诱导的延迟和变暖提前的情况下,综合效应可能会相互抵消(Lemoine et al., 2017),或者导致反应方向相同的加性效应(Sun et al., 2023)。同样,物种效应可能取决于气候环境,例如海拔高度,次优和相对紧张的条件会加剧一些反应(Gimenez-Benavides 等人,2011 年;Hegland & Gillespie,2024 年)。为了解决这些不确定性,我们在挪威西部开阔的北方森林的三个海拔高度,对两种长寿矮灌木在田间条件下对两种长寿矮灌木物候的影响进行了首次研究。我们使用 MeJA 模拟植物对一年昆虫爆发的生理抵抗反应(自上而下效应),并使用开顶室 (OTC) 来模拟持续的夏季变暖(自下而上效应)。然后,我们跟踪了两种植物物种,它们根据海拔和最佳生长条件以不同的方式对两种处理做出反应。越桔(越橘)是一种早开花的落叶树种,在挪威的中海拔地区(约 450 m.a.s.l.)茁壮成长,对 MeJA 表现出典型的诱导防御反应(生长减少和食草动物损伤;Benevenuto等人,2020 年),尽管已经报道了非处方药对变暖的相互矛盾的物候反应(Anadon-Rosell 等人,2014 年;Prieto et al., 2009)。 晚开花且体型较小的常绿灌木V. vitis-idaea(越橘)耐旱,在低海拔和温暖的海拔地区表现良好,不仅对诱导防御的反应较弱(Hegland & Gillespie,2024),而且在人工变暖下也促进了物候学的发展(Rosa等人,2015)。在这两个物种中,越橘自然比越橘更容易受到食草动物的伤害(例如 Kozlov 等人,2015 年)。

使用我们的联合处理和研究物种,我们旨在量化营养和生殖物候反应,并以繁殖输出的形式确定对植物适应性的影响。我们的第一个研究问题是 (1) 实验性变暖和诱导食草抗性的联合处理对三个不同海拔的越橘和越橘的营养和繁殖物候有什么影响?根据这些植物以前的反应,我们预计 (a) 在变暖下的进展,在温度受限的高海拔地区进展最大,(b) 由于诱导抗性而导致的延迟,在施用 MeJA 后的一年内反应更强,以及 (c) 处理组合将在施用 MeJA 后的一年内相互抵消, 尽管我们最高的阿尔卑斯山地点的变暖可能会使植物对食草更具抵抗力(Hegland & Gillespie, 2024)。我们还预计越橘对治疗更敏感,因为它更容易受到干旱胁迫和昆虫爆发的影响(Taulavuori et al., 2013)。由于很少研究改变物候对植物适应性的影响以及与人口学相关的变量(Iler et al., 2021),我们进一步提出了问题 (2) 物候的变化在多大程度上影响了越橘和越橘的繁殖输出?我们用结构方程模型回答了这个问题,并假设物候的改变会因与传粉媒介的不匹配而对繁殖输出产生负面影响(Moreira等人,2019 年;Schat & Blossey,2005),但变暖对物候和植物发育的积极影响会抵消这些影响(Lemoine等人。,2017 年)。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号