American Journal of Hematology ( IF 10.1 ) Pub Date : 2024-12-09 , DOI: 10.1002/ajh.27542 Portia Smallbone, Mallika Sekhar, Samer A. Srour, Jeremy L. Ramdial, Crystal L. Carmicheal Kusy, Elizabeth J. Shpall, Uday R. Popat

|

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are associated with increased risk of splanchnic vein thrombosis (SVT), which contributes to morbidity and mortality. SVT, including portal, superior mesenteric, splenic, and hepatic vein thrombosis, disrupts portal pressures, leading to the development of portal hypertension (PHT) and complications such as varices, splenomegaly and liver failure, which increase the morbidity and mortality. The impact of prior SVT on outcomes of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) for myelofibrosis (MF) is not well understood. Although a small case series found a strong correlation between SVT and hyperbilirubinemia [1], the data is limited, making the optimal management of anticoagulation, hepatic comorbidities, and PHT sequelae challenging in this patient population. This study evaluates the impact of pre-existing SVT and its treatment on transplant outcomes.

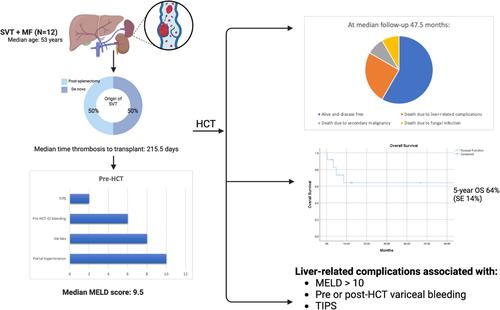

We screened 334 consecutive patients who underwent HCT for MF at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between January 2000 and August 2023 and identified 12 with pre-existing SVT. Patient characteristics, liver and thrombosis-related data, transplant details and outcomes were collected through retrospective review. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores were calculated using creatinine, bilirubin, INR, and sodium levels to stratify the degree of chronic liver dysfunction. Continuous variables are reported as median and range, while categorical variables as number and percentage. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

With regards to patient characteristics, the median age was 53 years (range: 39–73). Five patients had primary MF, four had post-essential thrombocythemia (PET-MF), and three had post-polycythaemia vera (PPV-MF). The majority (n = 8, 66.6%) were JAK2 V617F-positive. One patient was MPL positive. Patients received conditioning regimens based on institutional protocols, considering age and comorbidities. Individual characteristics and outcomes for all patients are summarized in Table 1. Other baseline characteristics are seen in Table S1.

| Patient | Age at transplant | Sex | JAK2 status | Additional mutations via NGS | Thrombosis type | Days SVT prior to transplant | Splenectomy prior to thrombosis | Yerdel classification | Anticoagulation | Date of transplant | Conditioning regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | F | Positive | No | Splenic vein thrombosis | 109 | No | NE | No | 3-Jul-23 | Bu/Cy |

| 2 | 70 | F | Positive | No | Portal vein, SMV and splenic vein thrombosis | 145 | Yes | 3 | Yes, 120 days | 14-Sep-22 | Flu/Mel |

| 3 | 72 | M | Positive | ASXL1, EZH2, GATA2, SF3B1 | Portal vein thrombosis | 74 | Yes | 1 | No | 29-Aug-22 | Flu/Bu |

| 4 | 52 | F | Positive | TP53 | Portal and SMV thrombosis | 503 | Yes | 2 | Yes, 180 days | 11-Sep-19 | Flu/Bu |

| 5 | 51 | F | Negative | MPL | Portal vein thrombosis | 234 | No | 2 | No | 9-Sep-19 | Flu/Bu |

| 6 | 39 | F | Positive | No | Portal vein thrombosis, splenic vein thrombus | 613 | No | 3 | Yes, 2 years | 30-Aug-16 | Flu/Mel/TBI |

| 7 | 46 | M | Positive |

NE |

Portal vein, SMV and IVC thrombosis | 4018 | No | 3 | No | 13-Dec-13 | Flu/Mel |

| 8 | 54 | F | Positive | NE | Portal vein thrombosis | 4748 | No | 3 | No, portocaval shunt | 15-Dec-09 | Flu/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 9 | 54 | F | Positive | NE | Portal and splenic vein thrombosis | 41 | Yes | NE | Yes, 252 days | 14-Sep-06 | Flu/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 10 | 73 | M | NE | NE | Portal vein thrombosis | 46 | Yes | 3 | Yes, 95 days | 24-Oct-05 | Flu/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 11 | 62 | M | NE | NE | Portal and splenic vein thrombosis | 197 | Yes | 1 | Yes, 125 days and TIPS | 9-Apr-03 | Flu/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 12 | 49 | F | NE | NE | SMV and splenic vein thrombosis, acute hepatic vein thrombus post-HCT | 1397 | No | NE | Yes | 12-Dec-00 | Flu/Bu/Thiotepa |

| (Continues) | |||||||||||

| Patient | Donor type | MELD score | Portal hypertension | Ascites | Varices | Variceal bleeding pre-transplantation ± intervention | Beta blocker use | GI bleeding post transplantation | Liver outcome in first 100 days | Clinical course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haplo | 8 | Yes | Yes | Esophageal | No | Yes | Major GI bleed day 3, 4 and 11, requiring splenic artery embolization | NAD | Uncomplicated |

| 2 | MUD | 8 | Yes | No | Esophageal | No | No | No | NAD | Uncomplicated |

| 3 | MSD | 7 | Yes | Yes | Esophageal, gallbladder | No | No | No | NAD | Uncomplicated |

| 4 | MUD | 8 | No | No | No | No | No | No | NAD | Uncomplicated |

| 5 | Haplo | 15 | Yes | Yes | Esophageal, gastric | Hematemesis requiring multiple banding procedures | Yes | No | Severe hyperbilirubinemia and VOD (day 4) | Decompensated liver failure with resultant encephalopathy (VOD), platelet refractoriness and intracranial hemorrhage |

| 6 | MUD | 9 | Yes | Yes | Esophageal, gastric | No, pre-emptive banding | Yes | Minor GI bleed day 1386 | NAD | Increased esophageal, splenic and gastric varices and splenomegaly |

| 7 | MMUD | 17 | Yes | Multiple ascitic paracenteses | Esophageal | Yes, variceal banding | Yes | Recurrent major GI bleeding days 12, 68, 84, 105, 111 | Grade I hyperbilirubinemia, Moderate transaminitis | Pleural effusions requiring recurrent drainage, progressive renal failure and death due to fungal pneumonia |

| 8 | MSD | 13 | Yes | Yes, requiring paracentesis | Esophageal | Yes | Yes | Recurrent major GI bleeding day 14 and 3223 | Grade I hyperbilirubinemia | Decompensated cirrhosis requiring paracentesis, liver GVHD. Relapse day 254 |

| 9 | MSD | 9 | No | No | No | No | No | No | NAD | Lost to follow up 2009 |

| 10 | MSD | 11 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Grade I transaminitis | Died of secondary malignancy |

| 11 | MSD | 10 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes, variceal banding | No | No | NAD | Recurrent admissions with encephalopathy and ascites requiring TIPS revisions |

| 12 | MSD | 13 | Yes | Yes, requiring paracentesis | Esophageal, gastric | No | No | Yes, day 236 | NAD | Recurrent admissions with ascites and encephalopathy requiring TIPS, developed severe GI bleeding with coagulopathy, liver failure |

Half of the patients developed SVT following splenectomy, while the other half developed de novo SVT. Three developed SVT within 100 days pre-HCT, all post-splenectomy. The median time from thrombosis to transplant was 215.5 (range: 41–4748) days. The median Yerdel score, describing the extent of thrombosis and risk of complication, was 3 (range: 1–3). Six (50%) patients had chronic SVT and were not anticoagulated pre-HCT. The remaining six (50%) received anticoagulation (DOAC or enoxaparin) for acute thrombosis, with a median duration of 180 days (95–1950). Three (42.8%) continued anticoagulation peri-HCT after platelet recovery. Further information is seen in Table S2.

With regards to liver-related characteristics, the median MELD score was 9.5 (range: 8–17). Most patients had radiologic evidence of PHT (n = 10; 83.3%) or varices (n = 8; 66.6%). Of those with varices, six (75%) had pre-HCT variceal bleeding. Two had pre-emptive banding of varices, and four received beta blocker prophylaxis. Two patients required pre-HCT intervention with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and portocaval shunt. No biopsy-proven cirrhosis or iron overload was found pre-HCT, though biopsies were only performed in 4/12 patients. No alternate causes of liver dysfunction were identified. Further information is seen in Table S3.

At Day 100, 11 (92%) patients were alive and disease-free. At a median follow up of 47.5 months, seven (66.6%) were alive and disease-free. Five-year overall survival was 64% (SE 14%). Five patients died: one from secondary malignancy (Day 2315), one from fungal infection related to poor graft function (Day 148), although recurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and ascites contributed to their decline, and three from direct liver-related complications (veno-occlusive disease [VOD] and intracranial hemorrhage, Day 12; liver failure on Day 103 and liver failure on 260).

For those patients who died from direct liver-related complications: the first patient (MELD 15, pre-HCT variceal bleeding requiring banding) developed severe VOD at Day 4 post-HCT and died of intracranial hemorrhage at Day 12. The second patient (MELD 10, pre-HCT variceal bleeding requiring banding) suffered liver failure following TIPS placement for portal and splenic vein thrombus at Day 62, leading to death on Day 103. The third patient (MELD 13) developed symptomatic ascites post-HCT with imaging revealing acute hepatic vein thrombus (BCS) and cavernous portal vein thrombus requiring TIPS placement on Day 95. She developed progressive liver failure and GI bleeding, dying at Day 260. Overall, liver-related complications were associated with pre-HCT MELD scores > 10, pre- or post-HCT variceal bleeding, TIPS placement, and failure of recanalization on post-HCT imaging.

Non-fatal liver-related complications included liver toxicity and progressive thrombosis. Grade 1 hyperbilirubinemia (n = 3; 25%) and Grade 1 transaminitis (n = 2; 17%) resolved without intervention by Day 100. Five patients (42%) developed long-term sequelae of PHT at a median of 146.5 days (range: 72–3304). These included decompensated ascites (n = 3; 33.3%), variceal bleeding requiring endoscopic management (n = 4; 33.3%), and encephalopathy in the setting of previous TIPS (n = 2; 16%). Median spleen size was 24 cm, and 75% had not undergone splenectomy. Recurrent GI bleeding post-HCT (median 76 days, range: 3–3323) occurred in patients with pre-HCT esophageal varices and no anticoagulation, despite beta blocker prophylaxis. New venous thromboembolism (VTE) was noted in four patients post-HCT, including three (75%) occurring while off anticoagulation. Three (75%) of these events occurred outside the splanchnic system (deep veins of the limbs and pulmonary embolism). Recanalization of SVT occurred in only 16% of patients.

Despite this, some patients had encouraging clinical outcomes at extended follow up. Patient 8 (MELD 8) experienced recurrent variceal bleeding and ascites requiring paracentesis up to 9 years post-HCT, but was alive and clinically stable at 12.5 years post-HCT with long-term hepatology follow-up and diuretic therapy. Patient 6 (MELD 9) developed increasing varices and splenomegaly post-HCT but remained disease-free with no liver toxicity 2577 days post-HCT.

This case series indicates that MF patients with pre-existing SVT can successfully undergo HCT, although they face liver and thrombosis-associated morbidity and mortality. Optimal management of SVT, particularly in the peri-HCT period, is not well studied. However, the rate of recurrent thrombosis in this setting is increased [2]. While anticoagulation in acute thrombosis improves recanalization and reduces PHT, it may increase bleeding, particularly in the setting of varices. Consideration of beta blockade or preemptive banding may mitigate this risk, although this has not been validated in MF. Chronic SVT rarely recanalizes, so life-long anticoagulation is generally recommended to reduce risk of recurrence. In our cohort, long-term anticoagulation, including peri-HCT, was not associated with bleeding, though the decision to continue anticoagulation peri-HCT should be individualized. Results with interventions such as TIPS, thrombolysis, and liver transplantation are variable in non-HCT patients. Portosystemic shunting shows a survival benefit in BCS patients, but its benefits in SVT remain unclear [3].

Management of splenomegaly pre- and peri-HCT is challenging. Splenectomy is often used in an attempt to reverse PHT and improve engraftment, however post-operative SVT rates are as high as 55% with laparoscopic approaches [4]. Morbidity may be significant, including intestinal ischemia and even death. Risk factors for SVT development include splenic weight, co-existent MPN, splenic/portal vein diameter, low white blood counts, and anatomic variation [5]. Half of the patients in our cohort developed SVT following splenectomy, but splenectomy itself did not appear to be associated with long-term morbidity.

MF patients are at risk of post-HCT hepatotoxicity due to iron overload, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and pre-existing PHT. Wong et al. found an increased risk of VOD in patients undergoing HCT for MF, with an association between SVT and hyperbilirubinemia [1]. In contrast, our data showed no persistent liver dysfunction after Day 100, suggesting that with appropriate patient selection, hepatic function is not compromised. One patient died due to complications of VOD, indicating the need for careful surveillance in the post-HCT period.

PHT is a common complication of MF, with potential etiologies including splenomegaly, PVT, extramedullary hematopoiesis and recently, sinusoidal fibrosis [1]. Resultant varices increase the risk of hemorrhage and ascites, leading to long-term morbidity. Thrombosis often contributes, with nearly half of non-HCT patients with JAK2 V617F-associated non-cirrhotic PVT developing PHT during follow-up [6]. In our cohort, sequelae of PHT were evident at Day 100, with persistent morbidity evident even after 12 years in some patients. Liver-related variables such as bilirubin, albumin, and INR, MELD score (> 10) and non-recanalization pre-HCT were key prognostic indicators in this cohort. Other high-risk clinical characteristics, including pre-HCT variceal bleeding, appear to predict similar bleeding post-HCT, regardless of intervention. Pre-HCT optimization, such as variceal banding, may improve outcomes, although this is unclear. All patients undergoing HCT workup should have dedicated imaging for PHT, endoscopic evaluation for variceal treatment and long-term multidisciplinary follow up.

Our study, although limited by its small patient cohort, retrospective design, and the lack of representation of BCS or hepatic vein thrombus, suggests that HCT is feasible and curative for selected patients with SVT with low early and overall mortality. However, the long-term sequelae of PHT remain a concern. Factors such as variceal bleeding and MELD score > 10 appear to increase the risk of future morbidity and mortality related to PHT. Multidisciplinary pre-HCT evaluation including dedicated imaging for PHT, screening and pre-emptive treatment of varices, and long-term follow up contribute to successful outcomes in this patient population. Larger studies are needed to validate these results and refine risk stratification for patients with SVT undergoing HCT.

中文翻译:

骨髓纤维化和内脏静脉血栓形成患者的造血干细胞移植:病例系列

骨髓增生性肿瘤 (MPN) 与内脏静脉血栓形成 (SVT) 风险增加有关,这导致发病率和死亡率。SVT,包括门静脉、肠系膜上静脉、脾静脉和肝静脉血栓形成,破坏门静脉压,导致门静脉高压症 (PHT) 和静脉曲张、脾肿大和肝功能衰竭等并发症的发展,从而增加发病率和死亡率。既往 SVT 对接受同种异体造血干细胞移植 (HCT) 治疗骨髓纤维化 (MF) 的患者结局的影响尚不清楚。尽管一项小型病例系列研究发现 SVT 与高胆红素血症之间存在很强的相关性 [1],但数据有限,这使得该患者群体的抗凝治疗、肝脏合并症和 PHT 后遗症的最佳管理具有挑战性。本研究评估了先前存在的 SVT 及其治疗对移植结果的影响。

我们筛选了 2000 年 1 月至 2023 年 8 月期间在德克萨斯大学 MD 安德森癌症中心连续接受 334 例 CFT 的患者,并确定了 12 例既往存在 SVT。通过回顾性评价收集患者特征、肝脏和血栓形成相关资料、移植细节和结局。使用肌酐、胆红素、 INR 和钠水平计算终末期肝病模型 (MELD) 评分,以对慢性肝功能障碍的程度进行分层。连续变量报告为中位数和范围,而分类变量报告为数字和百分比。使用 Kaplan-Meier 方法估计总生存期。

关于患者特征,中位年龄为 53 岁 (范围: 39-73)。5 例患者为原发性 MF,4 例为原发性血小板增多症后 (PET-MF),3 例为真性红细胞增多症后 (PPV-MF)。大多数 (n = 8, 66.6%) 为 JAK2 V617F 阳性。1 例患者为 MPL 阳性。患者接受基于机构方案的预处理方案,考虑年龄和合并症。表 1 总结了所有患者的个体特征和结果。其他基线特征见表 S1。

表 1. 详细的患者特征。

| 病人 | 移植年龄 | 性 | JAK2 状态 | 通过 NGS 进行其他突变 |

血栓形成类型 | 移植前 SVT 天数 |

血栓形成前的脾切除术 |

Yerdel 分类 | 抗凝 | 移植日期 | 预处理方案 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | F | 阳性 | 不 | 脾静脉血栓形成 | 109 | 不 | NE | 不 | 3-七月-23 | Bu/Cy |

| 2 | 70 | F | 阳性 | 不 | 门静脉、SMV 和脾静脉血栓形成 |

145 | 是的 | 3 | 是的,120 天 | 14-九月-22 | 流感/梅尔 |

| 3 | 72 | M | 阳性 | ASXL1、EZH2、GATA2、SF3B1 |

门静脉血栓形成 | 74 | 是的 | 1 | 不 | 29-八月-22 | 流感/Bu |

| 4 | 52 | F | 阳性 | TP53 | 门静脉血栓形成和 SMV 血栓形成 |

503 | 是的 | 2 | 是的,180 天 | 11-九月-19 | 流感/Bu |

| 5 | 51 | F | 阴性 | MPL | 门静脉血栓形成 | 234 | 不 | 2 | 不 | 9-九月-19 | 流感/Bu |

| 6 | 39 | F | 阳性 | 不 | 门静脉血栓形成、脾静脉血栓 |

613 | 不 | 3 | 是的,2 年 | 30-八月-16 | 流感/梅尔/TBI |

| 7 | 46 | M | 阳性 |

NE |

门静脉、SMV 和 IVC 血栓形成 |

4018 | 不 | 3 | 不 | 13 年 12 月 13 日 | 流感/梅尔 |

| 8 | 54 | F | 阳性 | NE | 门静脉血栓形成 | 4748 | 不 | 3 | 否,门腔静脉分流术 | 15-十二月-09 | 流感/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 9 | 54 | F | 阳性 | NE | 门静脉和脾静脉血栓形成 |

41 | 是的 | NE | 是的,252 天 | 06 年 9 月 14 日 | 流感/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 10 | 73 | M | NE | NE | 门静脉血栓形成 | 46 | 是的 | 3 | 是的,95 天 | 05 年 10 月 24 日 | 流感/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 11 | 62 | M | NE | NE | 门静脉和脾静脉血栓形成 |

197 | 是的 | 1 | 是的,125 天和 TIPS |

4月 9, 03 | 流感/Bu/Thiotepa |

| 12 | 49 | F | NE | NE | SMV 和脾静脉血栓形成,HCT 后急性肝静脉血栓 |

1397 | 不 | NE | 是的 | 12月 12, Dec-00 | 流感/Bu/Thiotepa |

| (续) | |||||||||||

| 病人 | 供体类型 | MELD 评分 | 门静脉高压症 | 腹水 | 静脉曲张 | 移植前静脉曲张出血 ± 干预 |

β 受体阻滞剂的使用 | 移植后胃肠道出血 |

前 100 天的肝脏结局 |

临床病程 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 单倍体 | 8 | 是的 | 是的 | 食管 | 不 | 是的 | 第 3 天、第 4 天和第 11 天严重胃肠道出血,需要脾动脉栓塞术 |

NAD | 简单 |

| 2 | MUD | 8 | 是的 | 不 | 食管 | 不 | 不 | 不 | NAD | 简单 |

| 3 | MSD | 7 | 是的 | 是的 | 食管、胆囊 | 不 | 不 | 不 | NAD | 简单 |

| 4 | MUD | 8 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | NAD | 简单 |

| 5 | 单倍体 | 15 | 是的 | 是的 | 食管、胃 | 需要多次束扎手术的呕血 |

是的 | 不 | 严重高胆红素血症和 VOD(第 4 天) |

失代偿性肝功能衰竭伴导致的脑病 (VOD)、血小板难治性和颅内出血 |

| 6 | MUD | 9 | 是的 | 是的 | 食管、胃 | 否,抢占式带状 | 是的 | 轻微胃肠道出血第 1386 天 |

NAD | 食管、脾和胃底静脉曲张和脾肿大增加 |

| 7 | MMUD | 17 | 是的 | 多发性腹水腹腔穿刺术 |

食管 | 是的,静脉曲张束扎术 | 是的 | 复发性大消化道出血第 12、68、84、105、111 天 |

I 级高胆红素血症,中度转氨酶 |

需要反复引流的胸腔积液、进行性肾功能衰竭和真菌性肺炎导致的死亡 |

| 8 | MSD | 13 | 是的 | 是的,需要穿刺术 |

食管 | 是的 | 是的 | 复发性大消化道出血第 14 天和第 3223 天 |

I 级高胆红素血症 |

需要穿刺术的失代偿期肝硬化、肝脏 GVHD。复发日 254 |

| 9 | MSD | 9 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | 不 | NAD | 2009 年失踪 |

| 10 | MSD | 11 | 是的 | 是的 | 不 | 是的 | 不 | 不 | I 级转氨酶 | 死于继发性恶性肿瘤 |

| 11 | MSD | 10 | 是的 | 是的 | 不 | 是的,静脉曲张束扎术 | 不 | 不 | NAD | 因脑病和腹水需要修订 TIPS 的反复入院 |

| 12 | MSD | 13 | 是的 | 是的,需要穿刺术 |

食管、胃 | 不 | 不 | 是的,第 236 天 | NAD | 因腹水和脑病需要 TIPS 的反复入院,发展为严重的胃肠道出血伴凝血功能障碍,肝功能衰竭 |

一半的患者在脾切除术后发生 SVT,而另一半患者发生新发 SVT。3 例在 HCT 前 100 天内发生 SVT,均在脾切除术后发生。从血栓形成到移植的中位时间为 215.5 (范围: 41-4748) 天。描述血栓形成程度和并发症风险的中位 Yerdel 评分为 3 分(范围:1-3)。6 例 (50%) 患者患有慢性 SVT,HCT 前未接受抗凝治疗。其余 6 例 (50%) 接受抗凝治疗 (DOAC 或依诺肝素) 治疗急性血栓形成,中位持续时间为 180 天 (95-1950)。3 例 (42.8%) 在血小板恢复后 HCT 围期继续抗凝治疗。更多信息见表 S2。

关于肝脏相关特征,中位 MELD 评分为 9.5 (范围:8-17)。大多数患者有 PHT (n = 10;83.3%) 或静脉曲张 (n = 8;66.6%) 的放射学证据。在静脉曲张患者中,6 例 (75%) 有 HCT 前静脉曲张出血。2 例有先发性静脉曲张带,4 例接受 β 受体阻滞剂预防。2 例患者需要经颈静脉肝内门体分流术 (TIPS) 和门腔静脉分流术的 HCT 前干预。HCT 前未发现活检证实的肝硬化或铁过载,但仅在 4/12 例患者中进行了活检。未发现肝功能障碍的其他原因。更多信息见表 S3。

第 100 天,11 例 (92%) 患者存活且无病。在中位随访 47.5 个月时,7 例 (66.6%) 存活且无病。五年总生存率为 64% (SE 14%)。5 例患者死亡:1 例死于继发性恶性肿瘤(第 2315 天),1 例死于与移植物功能不良相关的真菌感染(第 148 天),尽管复发性胃肠道 (GI) 出血和腹水导致其下降,3 例死于直接肝脏相关并发症(静脉闭塞性疾病 [VOD] 和颅内出血,第 12 天;第 103 天肝功能衰竭,第 260 天肝功能衰竭)。

对于那些死于直接肝脏相关并发症的患者:首例患者 (MELD 15,需要束带术的 HCT 前静脉曲张出血) 在 HCT 后第 4 天出现严重的 VOD,并在第 12 天死于颅内出血。第二名患者 (MELD 10,需要束扎术的 HCT 前静脉曲张出血) 在第 62 天放置门静脉和脾静脉血栓后出现肝功能衰竭,导致第 103 天死亡。第 3 例患者 (MELD 13) 在 HCT 后出现症状性腹水,影像学显示急性肝静脉血栓 (BCS) 和海绵状门静脉血栓,需要在第 95 天放置 TIPS。她出现进行性肝衰竭和胃肠道出血,在第 260 天死亡。总体而言,肝脏相关并发症与 HCT 前 MELD 评分 > 10、HCT 前后静脉曲张出血、TIPS 放置以及 HCT 后影像学再通失败相关。

非致死性肝脏相关并发症包括肝毒性和进行性血栓形成。到第 100 天,1 级高胆红素血症 (n = 3; 25%) 和 1 级转氨酶炎 (n = 2; 17%) 无需干预即可消退。5 例患者 (42%) 在中位 146.5 天 (范围: 72-3304) 时出现 PHT 的长期后遗症。这些包括失代偿性腹水 (n = 3; 33.3%)、需要内窥镜治疗的静脉曲张出血 (n = 4; 33.3%) 和既往 TIPS 情况下的脑病 (n = 2; 16%)。中位脾大为 24 cm,75% 未接受脾切除术。尽管接受了 β 受体阻滞剂预防,但 HCT 后食管静脉曲张患者(中位 76 天,范围:3-3323)发生复发性胃肠道出血。4 例 HCT 后患者出现新发静脉血栓栓塞 (VTE),其中 3 例 (75%) 发生在停用抗凝治疗期间。其中 3 例 (75%) 发生在内脏系统之外 (四肢深静脉和肺栓塞)。仅 16% 的患者发生 SVT 再通。

尽管如此,一些患者在长期随访中取得了令人鼓舞的临床结局。患者 8 (MELD 8) 在 HCT 后长达 9 年内出现复发性静脉曲张出血和需要穿刺术的腹水,但在 HCT 后 12.5 年存活且临床稳定,并接受长期肝病随访和利尿剂治疗。患者 6 (MELD 9) 在 HCT 后出现静脉曲张增加和脾肿大,但在 HCT 后 2577 天仍无病,无肝毒性。

该病例系列表明,已有 SVT 的 MF 患者可以成功接受 HCT,尽管他们面临与肝脏和血栓形成相关的发病率和死亡率。SVT 的最佳管理,尤其是在 HCT 围期,尚未得到很好的研究。然而,在这种情况下,血栓复发的发生率会增加[2]。虽然急性血栓形成的抗凝治疗可改善再通并减少 PHT,但它可能会增加出血,尤其是在静脉曲张的情况下。考虑 β 受体阻滞或先发制人条带可能会减轻这种风险,尽管这尚未在 MF 中得到验证。慢性 SVT 很少再通,因此通常建议终身抗凝治疗以降低复发风险。在我们的队列中,长期抗凝治疗(包括 HCT 围期)与出血无关,但继续抗凝围 HCT 的决定应个体化。非 HCT 患者使用 TIPS、溶栓和肝移植等干预措施的结果存在差异。门体分流术在 BCS 患者中显示出生存获益,但其在 SVT 中的获益仍不清楚 [3]。

HCT 前和周围脾肿大的管理具有挑战性。脾切除术通常用于逆转 PHT 和改善植入,但腹腔镜入路的术后 SVT 发生率高达 55% [4]。并发症发生率可能很高,包括肠缺血甚至死亡。发生 SVT 的危险因素包括脾重量、共存 MPN、脾/门静脉直径、白细胞计数低和解剖变异 [5]。我们队列中一半的患者在脾切除术后发生 SVT,但脾切除术本身似乎与长期发病率无关。

由于铁超负荷、髓外造血和预先存在的 PHT,MF 患者有发生 HCT 后肝毒性的风险。Wong 等人发现,接受 HCT 治疗 MF 的患者发生 VOD 的风险增加,SVT 与高胆红素血症之间存在关联 [1]。相比之下,我们的数据显示第 100 天后没有持续的肝功能障碍,这表明通过适当的患者选择,肝功能不会受到影响。1 例患者死于 VOD 并发症,表明需要在 HCT 后进行仔细监测。

PHT 是 MF 的常见并发症,潜在病因包括脾肿大、PVT、髓外造血和最近的窦状纤维化 [1]。由此产生的静脉曲张会增加出血和腹水的风险,导致长期并发症。血栓形成常是原因,近半数的 JAK2 V617F 相关非肝硬化 PVT 的非 HCT 患者在随访期间发生 PHT [6]。在我们的队列中,PHT 的后遗症在第 100 天很明显,一些患者即使在 12 年后也存在持续的并发症。肝脏相关变量如胆红素、白蛋白和 INR、MELD 评分 (> 10) 和非再通前 HCT 是该队列的关键预后指标。其他高危临床特征,包括 HCT 前静脉曲张出血,似乎可以预测 HCT 后类似的出血,无论是否干预。HCT 前优化,例如静脉曲张束扎术,可能会改善结局,但尚不清楚。所有接受 HCT 病情检查的患者都应进行专门的 PHT 影像学检查、静脉曲张治疗的内窥镜评估和长期多学科随访。

我们的研究虽然受到患者队列小、回顾性设计以及缺乏 BCS 或肝静脉血栓代表的限制,但表明 HCT 对于早期和总体死亡率低的特定 SVT 患者是可行的和治愈的。然而,PHT 的长期后遗症仍然令人担忧。静脉曲张出血和 MELD 评分 > 10 等因素似乎会增加与 PHT 相关的未来发病率和死亡率的风险。多学科 HCT 前评估,包括 PHT 的专用成像、静脉曲张的筛查和先发制人治疗以及长期随访,有助于该患者群体的成功结局。需要更大规模的研究来验证这些结果并改进接受 HCT 的 SVT 患者的风险分层。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号