Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-10-18 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14434 Saara Luukkonen, Jani Heino, Jan Hjort, Aveliina Helm, Janne Alahuhta

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Freshwater environments are among those most affected by human influence in the world, facing a more severe biodiversity loss compared to terrestrial or marine realms (Harrison et al., 2018; Tickner et al., 2020). With an area of less than 1% of Earth's surface, freshwater environments host 10% of all species and notably high levels of endemic species (Strayer & Dudgeon, 2010). Threats such as water pollution, overexploitation, habitat degradation and climate change have affected and are expected to continue adversely affecting freshwater species and ecosystems (Albert et al., 2020; Dudgeon et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2019). These factors, among others, account for the exceptionally high extinction rates among freshwater organisms (Reid et al., 2019). Despite the excessive loss of biodiversity they have already experienced, freshwater systems have received little attention in conservation strategies compared to terrestrial systems (Higgins et al., 2021). Although freshwater systems are dependent on the surrounding terrestrial environments, biodiversity protection based only on terrestrial conservation planning may not sufficiently benefit freshwater biodiversity (Leal et al., 2020). To halt further decreases in freshwater biodiversity, conservation planning also requires consideration at scales from local to global and supporting research on several aspects of freshwater biodiversity (Albert et al., 2020). A useful starting point is to examine spatial variation in biodiversity across equal-area grid cells at continental scale, which pinpoints areas that may require direct fine-scale assessments of freshwater biodiversity.

Understanding the patterning of biodiversity in space is one of the key issues in conservation science (Socolar et al., 2016). This can be addressed, for example, by the concept of beta diversity, or the spatial variation of species composition between different species assemblages (Legendre et al., 2005). A particularly promising measure for conservation associated with beta diversity is the local contribution to beta diversity (LCBD), in which the total beta diversity is partitioned into additive components (Legendre & De Cáceres, 2013). In brief, LCBD values represent the ecological uniqueness of separate species assemblages and how they contribute to the total beta diversity in the area examined. Thus, high LCBD values indicate assemblages with exceptional species compositions and hence potential conservation value compared to other assemblages in a study area (Legendre & De Cáceres, 2013). Based on ecological uniqueness values, even species-poor assemblages may be important targets for conservation, which advocates preserving not only sites with high taxonomic richness but also sites with high ecological uniqueness (Heino et al., 2022; Hill et al., 2021).

Ecological uniqueness patterns in freshwater ecosystems have been under increasing interest in recent years (e.g. Heino & Grönroos, 2017: insects; Vilmi et al., 2017: diatoms; Gavioli et al., 2019: fish; Schneck et al., 2022: diatoms and insects). Here, we apply the approach to freshwater macrophytes, a basal group in freshwater ecosystems. Macrophytes serve as ecosystem engineers, influencing the structure and functioning of freshwater ecosystems (Chambers et al., 2008). For example, they provide keystone structures for other organisms, such as sheltering and microhabitats for zooplankton (Cazzanelli et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2014). They also influence water hydrology, sedimentation and nutrient cycling (Thomaz, 2023) and provide food for other organisms (Wood et al., 2017). Like the majority of previous ecological uniqueness studies (e.g. D'Antraccoli et al., 2020; Niskanen et al., 2017; Xia et al., 2022), most studies on ecological uniqueness of macrophyte assemblages have focused on small spatial extents with comparatively few sites sampled from lakes or rivers (e.g. Bomfim et al., 2023; Dey et al., 2024; Heino et al., 2022; Pozzobom et al., 2020). Studies of ecological uniqueness at continental scales have rarely been conducted (but see Dansereau et al., 2022) and, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to do so for freshwater macrophytes.

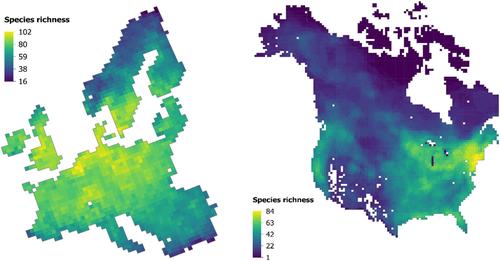

This study examined the factors affecting variation in the ecological uniqueness of freshwater macrophytes in North America and Europe and compared the ecological uniqueness patterns between the two continents. We studied the correlation between freshwater macrophyte species richness and ecological uniqueness separately in Europe and North America, adding new knowledge on species richness patterns compared to previous studies (Alahuhta et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2019). In addition, we investigated the variation in ecological uniqueness in relation to environmental characteristics in both continents. We hypothesized (H1) that ecological uniqueness would be negatively correlated with species richness in both study areas, as in many previous studies (e.g. Hill et al., 2021; Legendre & De Cáceres, 2013; Vilmi et al., 2017), including across a broad spatial extent for North American warblers (Dansereau et al., 2022). We presumed (H2) current climate to be a driver of ecological uniqueness of macrophytes at a continental scale, since it has also been found to affect species richness and mean range size of aquatic plants (Alahuhta et al., 2020). We also expected (H3) that LCBD values would be higher in areas with uncommon environmental conditions compared with other areas surveyed and that patterns would be similar in Europe and North America. This is supported by the idea that fewer species are adapted to harsh environments (Tan et al., 2019).

中文翻译:

欧洲和北美淡水大型植物组合生态独特性的宏观生态学分析

1 引言

Freshwater environments are among those most affected by human influence in the world, facing a more severe biodiversity loss compared to terrestrial or marine realms (Harrison et al., 2018; Tickner et al., 2020). With an area of less than 1% of Earth's surface, freshwater environments host 10% of all species and notably high levels of endemic species (Strayer & Dudgeon, 2010). Threats such as water pollution, overexploitation, habitat degradation and climate change have affected and are expected to continue adversely affecting freshwater species and ecosystems (Albert et al., 2020; Dudgeon et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2019). These factors, among others, account for the exceptionally high extinction rates among freshwater organisms (Reid et al., 2019). Despite the excessive loss of biodiversity they have already experienced, freshwater systems have received little attention in conservation strategies compared to terrestrial systems (Higgins et al., 2021). Although freshwater systems are dependent on the surrounding terrestrial environments, biodiversity protection based only on terrestrial conservation planning may not sufficiently benefit freshwater biodiversity (Leal et al., 2020). To halt further decreases in freshwater biodiversity, conservation planning also requires consideration at scales from local to global and supporting research on several aspects of freshwater biodiversity (Albert et al., 2020). A useful starting point is to examine spatial variation in biodiversity across equal-area grid cells at continental scale, which pinpoints areas that may require direct fine-scale assessments of freshwater biodiversity.

了解太空生物多样性的模式是保护科学的关键问题之一(Socolar et al., 2016)。例如,这可以通过 β 多样性的概念或不同物种组合之间物种组成的空间变化来解决(Legendre et al., 2005)。与β多样性相关的一个特别有前途的保护措施是对β多样性的本地贡献(LCBD),其中总β多样性被划分为加性成分(Legendre & De Cáceres,2013)。简而言之,LCBD 值代表了不同物种组合的生态独特性以及它们如何影响所研究区域的总 beta 多样性。因此,高LCBD值表明组合具有特殊的物种组成,因此与研究区域中的其他组合相比具有潜在的保护价值(Legendre & De Cáceres, 2013)。基于生态独特性值,即使是物种贫乏的组合也可能成为保护的重要目标,这主张不仅要保护分类丰富度高的地点,还要保护生态独特性高的地点(Heino 等人,2022 年;Hill et al., 2021)。

近年来,淡水生态系统中的生态独特性模式受到了越来越多的关注(例如Heino & Grönroos,2017年:昆虫;Vilmi et al., 2017: 硅藻;Gavioli et al., 2019: 鱼;Schneck 等人,2022 年:硅藻和昆虫)。在这里,我们将该方法应用于淡水大型植物,淡水生态系统中的一个基底类群。大型植物充当生态系统工程师,影响淡水生态系统的结构和功能(Chambers et al., 2008)。例如,它们为其他生物提供了关键结构,例如浮游动物的庇护所和微栖息地(Cazzanelli et al., 2008;Choi et al., 2014)。它们还影响水文、沉积和营养循环(Thomaz,2023 年),并为其他生物提供食物(Wood 等人,2017 年)。与之前的大多数生态独特性研究一样(例如 D'Antraccoli 等人,2020 年;Niskanen et al., 2017;Xia et al., 2022),大多数关于大型植物组合生态独特性的研究都集中在较小的空间范围内,从湖泊或河流中采样的地点相对较少(例如 Bomfim et al., 2023;Dey 等人,2024 年;Heino et al., 2022;Pozzobom et al., 2020)。很少对大陆尺度的生态独特性进行研究(但参见 Dansereau 等人,2022 年),据我们所知,本研究是第一个对淡水大型植物进行研究的研究。

本研究考察了影响北美和欧洲淡水大型植物生态独特性变化的因素,并比较了两大洲的生态独特性模式。我们分别研究了欧洲和北美淡水大型植物物种丰富度与生态独特性之间的相关性,与以前的研究相比,增加了关于物种丰富度模式的新知识(Alahuhta et al., 2020;Murphy等人,2019 年)。此外,我们还调查了两大洲生态独特性与环境特征相关的变化。我们假设 (H1) 生态独特性与两个研究领域的物种丰富度呈负相关,就像之前的许多研究一样(例如 Hill 等人,2021 年;勒让德和德卡塞雷斯,2013 年;Vilmi et al., 2017),包括北美莺的广泛空间范围(Dansereau et al., 2022)。我们假设 (H2) 当前气候是大陆尺度上大型植物生态独特性的驱动因素,因为它也被发现会影响水生植物的物种丰富度和平均范围大小(Alahuhta et al., 2020)。我们还预计 (H3) 与调查的其他地区相比,环境条件不常见的地区的 LCBD 值会更高,并且欧洲和北美的模式会相似。适应恶劣环境的物种较少的观点支持了这一点(Tan et al., 2019)。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号