Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-08-29 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14399 Erica Rievrs Borges 1, 2 , Maxime Réjou‐Méchain 1 , Sylvie Gourlet‐Fleury 3 , Grégoire Vincent 1 , Frédéric Mortier 3, 4 , Xaxier Bry 5 , Guillaume Cornu 3 , Fidèle Baya 6 , Félix Allah‐Barem 7 , Raphaël Pélissier 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Biodiversity ecosystem function (BEF) relationships aim to elucidate the ecological mechanisms underlying the impact of diversity on ecosystem functioning, such as productivity, stability and nutrient dynamics (Tilman et al., 2014). Specifically, understanding the importance of biodiversity in supporting biomass dynamics is critical for anticipating the impacts of biodiversity loss on the terrestrial carbon balance (Pan et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2017) and assessing potential co-benefits in conservation planning (Mori et al., 2021; Osuri et al., 2020). However, the causal link between these two ecosystem components has not yet been completely resolved for a range of ecosystems (van der Plas, 2019), such as hyper-diverse tropical forests, which constitute an ideal study case given their outstanding diversity and biomass stock.

Initial BEF models proposed the existence of a positive correlation between diversity and resource-use intensity (Loreau, 1998; Tilman et al., 1997). These theoretical studies were validated by experimental research conducted in simplified systems, where multispecies polycultures were shown to have higher biomass productivity than monocultures (Cadotte, 2013, 2017; Loreau & Hector, 2001). Despite the great contributions of these pioneering studies, the strength and direction of BEF relationships were found to vary strongly among natural communities (van der Plas, 2019). In particular, observational (non-manipulative) studies examining the direct influence of diversity on productivity and biomass accumulation have reported divergent results in forested ecosystems (Borges et al., 2021; Lasky et al., 2014; Morin, 2015; Morin et al., 2011; Satdichanh et al., 2018). Different ecological mechanisms are expected to generate positive associations between diversity and productivity. One important class of studies explores species niche differences and predicts that plant communities consisting of multiple species that occupy different niches can partition limited resources more efficiently, providing greater productivity than that expected from monocultures (Hector et al., 1999; Hooper & Dukes, 2004; Van de Peer et al., 2018). For instance, light is the main limiting resource in forests (Terborgh, 1985; Wright & van Schaik, 1994) and diverse communities are expected to better occupy different forest strata, leading to improved light interception, reduced competition and increased stand volume and productivity (Duarte et al., 2021; Guillemot et al., 2020). This more efficient use of the canopy space modifies the forest structure, allowing trees to pack more densely (Jucker et al., 2015) and is therefore hereafter referred to as ‘tree-packing effects’. Another type of biodiversity effect on productivity is that hyper-diverse communities have a greater chance of containing species with high-performance traits that could become dominant (due to large fitness differences) and drive ecosystem functioning (Hector et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2020; Loreau & Hector, 2001) through the mass-ratio effect (i.e., biomass productivity driven by the functional identity of the most dominant species; Grime, 1998). This biodiversity effect is hereafter referred to as ‘sampling effect’ (previously also referred to as selection probability effects; Huston, 1997). However, the relative importance of the ecological mechanisms driving BEF relationships in natural communities remains largely unknown (Cavanaugh et al., 2014; Finegan et al., 2015; Grace et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2019).

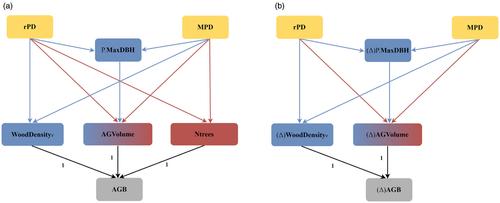

Here, we assumed that diversity acts in forest biomass and productivity through different pathways and that their joint effects can be disentangled by disaggregating forest biomass into its components: the number of trees, the tree volume and the wood density. Most BEF studies indeed ignored the fact that there are several ways to build forest biomass at the stand level, that is, with a higher number of trees, with larger trees or with higher wood density. Because diversity may act separately and simultaneously on each of the biomass components through different ecological mechanisms, these different effects may add up to each other, potentially leading to confounding effects.

Previous studies conducted on forest ecosystems have suggested that the effect of diversity on biomass and productivity is context-dependent, because of differences in environmental and historical contexts (Van de Peer et al., 2018). In particular, forest disturbances cause shifts in species diversity and composition and generally reduce the mean wood density and volume in the short term, which alters competitive interactions between individuals and allows competitors to coexist where they would normally be excluded (Carreño-Rocabado et al., 2012; Slik et al., 2008). These shifts are mainly caused by increased light availability in the understory following forest structure modifications (Yamamoto, 1992), which may alter the BEF relationship observed in undisturbed communities. Given the rapid erosion of biodiversity (IPBES, 2019) and loss of undisturbed tropical forests (Vancutsem et al., 2021), it is important to understand if and how the relationship between diversity and ecosystem functioning is altered in second-growth tropical forests, which are currently estimated to represent half of the global tropical forests (FAO, 2020).

Quantitative information on species traits and phylogeny is known to better predict ecosystem functions than more commonly used metrics of diversity such as species richness (Potter & Woodall, 2014). Indeed, communities with functionally dissimilar species tend to have greater resource-use complementarity and reduced competition (van der Plas, 2019). In this regard, evolutionary distances are known to correlate with multidimensional phenotypic differences among species, because phylogenetic diversity encapsulates a wide range of information about species complementarity across space and time (Faith, 1992). Evolutionary diversity was even shown to be a better predictor of productivity than some easily measured, or ‘soft’, functional traits (e.g. specific leaf area, seed weight and height). This suggests that unmeasured traits that are significantly related to phylogenetic relationships, such as root architecture, root morphology, resource requirements or other critical physiological differences, could contribute to maximizing productivity (Cadotte et al., 2009; Tucker et al., 2018). Besides, experimental evidence also suggests that the effect of phylogenetic diversity on productivity is likely to be a result of increased functional complementarity among lineages (Cadotte, 2013; Huang et al., 2020). Indeed, many studies have revealed that phylogenetic diversity can explain ecosystem function (biomass accumulation), stability and community biomass productivity better than measures of species richness (Coelho de Souza et al., 2019; Lasky et al., 2014; Paquette et al., 2015; Potter & Woodall, 2014; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2021; Satdichanh et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2020) and better than functional diversity (Flynn et al., 2011; Larkin et al., 2015) based on the hypothesis that relevant traits are phylogenetically conserved (Coelho de Souza et al., 2016; Srivastava et al., 2012).

Here, we used an experimental site established in 1982 in the Central African Republic to assess the effect of evolutionary diversity on forest biomass and productivity in different disturbance contexts. We specifically aimed to (1) disentangle the effects of diversity on different biomass components to better understand if and how different ecological mechanisms jointly determine the diversity-productivity relationship in natural tropical forests and (2) test whether historical disturbances influence the effect of diversity on biomass and biomass productivity. We predicted that the effect of diversity on biomass productivity varies between undisturbed and disturbed forests. In disturbed forests, overwhelming fitness differences could prevent complementarity due to the dominance of a few resource-acquisitive and highly productive species (Jucker et al., 2020; Reich et al., 2012; Tobner et al., 2016) while undisturbed forests are often characterized by more diverse tree communities that compete under resource-limiting conditions (Lohbeck, Poorter, et al., 2015; Pacala & Tilman, 2001).

中文翻译:

进化多样性通过干扰介导的生态途径影响热带森林的生物量和生产力

1 引言

生物多样性生态系统功能 (BEF) 关系旨在阐明多样性对生态系统功能(如生产力、稳定性和营养动态)影响的潜在生态机制(Tilman et al., 2014)。具体来说,了解生物多样性在支持生物量动态方面的重要性对于预测生物多样性丧失对陆地碳平衡的影响至关重要(Pan et al., 2011;Sullivan et al., 2017) 和评估保护规划中的潜在协同效益(Mori et al., 2021;Osuri et al., 2020)。然而,对于一系列生态系统,这两个生态系统组成部分之间的因果关系尚未完全解决(van der Plas,2019),例如高度多样化的热带森林,鉴于其出色的多样性和生物量存量,这些生态系统构成了一个理想的研究案例。

最初的 BEF 模型表明多样性与资源利用强度之间存在正相关关系(Loreau,1998 年;Tilman et al., 1997)。这些理论研究通过在简化系统中进行的实验研究得到验证,其中多物种混养被证明比单一栽培具有更高的生物量生产力(Cadotte,2013,2017; Loreau和Hector,2001年)。尽管这些开创性研究做出了巨大贡献,但发现 BEF 关系的强度和方向在自然群落之间差异很大(van der Plas,2019 年)。特别是,考察多样性对生产力和生物量积累的直接影响的观察性(非操纵性)研究报告了森林生态系统的不同结果(Borges 等人,2021 年;Lasky等人,2014 年;Morin, 2015;Morin et al., 2011;Satdichanh et al., 2018)。预计不同的生态机制将在多样性和生产力之间产生积极的关联。一类重要的研究探讨了物种生态位的差异,并预测由占据不同生态位的多个物种组成的植物群落可以更有效地分配有限的资源,从而提供比单一栽培预期的更高的生产力(Hector et al., 1999;Hooper & Dukes, 2004;Van de Peer等人,2018 年)。 例如,光是森林中的主要限制资源(Terborgh, 1985;Wright & van Schaik,1994年)和多样化的社区有望更好地占据不同的森林层,从而提高光拦截,减少竞争,增加林分体积和生产力(Duarte等人,2021年;Guillemot et al., 2020)。这种对树冠空间的更有效利用改变了森林结构,使树木能够更密集地聚集(Jucker et al., 2015),因此在下文中被称为“树木聚集效应”。生物多样性对生产力的另一种影响是,高度多样化的群落更有可能包含具有高性能特征的物种,这些物种可能成为主导物种(由于巨大的适应性差异)并驱动生态系统功能(Hector 等人,2002 年;Huang et al., 2020;Loreau & Hector,2001年)通过质量比效应(即,由最主要物种的功能特性驱动的生物质生产力;Grime,1998 年)。这种生物多样性效应在下文中被称为“抽样效应”(以前也称为选择概率效应;Huston,1997 年)。然而,驱动自然群落中 BEF 关系的生态机制的相对重要性在很大程度上仍然未知(Cavanaugh 等人,2014 年;Finegan 等人,2015 年;Grace et al., 2016;Luo等人,2019 年)。

在这里,我们假设多样性通过不同的途径影响森林生物量和生产力,并且可以通过将森林生物量分解为其组成部分来解开它们的联合效应:树木数量、树木体积和木材密度。大多数 BEF 研究确实忽略了这样一个事实,即有几种方法可以在林分水平上建立森林生物量,即使用更多的树木、更大的树木或更高的木材密度。由于多样性可能通过不同的生态机制单独和同时作用于每个生物质成分,因此这些不同的影响可能会相互叠加,从而可能导致混杂效应。

先前对森林生态系统进行的研究表明,由于环境和历史背景的差异,多样性对生物量和生产力的影响取决于环境(Van de Peer 等,2018)。特别是,森林干扰会导致物种多样性和组成发生变化,通常会在短期内降低平均木材密度和体积,从而改变个体之间的竞争互动,并允许竞争者在通常被排除在外的地方共存(Carreño-Rocabado 等人,2012 年;Slik et al., 2008)。这些变化主要是由于森林结构修改后林下光照可用性增加引起的(Yamamoto, 1992),这可能会改变在未受干扰的群落中观察到的 BEF 关系。鉴于生物多样性的快速侵蚀(IPBES,2019 年)和未受干扰的热带森林的丧失(Vancutsem 等人,2021 年),重要的是要了解次生热带森林的多样性与生态系统功能之间的关系是否以及如何发生变化,目前估计次生热带森林占全球热带森林的一半(粮农组织,2020 年)。

众所周知,关于物种特征和系统发育的定量信息比更常用的多样性指标(如物种丰富度)更能预测生态系统功能(Potter & Woodall, 2014)。事实上,具有功能差异物种的群落往往具有更大的资源利用互补性和更少的竞争(van der Plas,2019)。在这方面,已知进化距离与物种之间的多维表型差异相关,因为系统发育多样性囊括了有关跨空间和时间物种互补性的广泛信息(Faith,1992)。进化多样性甚至被证明比一些易于测量或“软”的功能性状(例如比叶面积、种子重量和高度)更能预测生产力。这表明与系统发育关系显着相关的未测量性状,例如根结构、根形态、资源需求或其他关键的生理差异,可能有助于最大限度地提高生产力(Cadotte 等人,2009 年;Tucker et al., 2018)。此外,实验证据还表明,系统发育多样性对生产力的影响可能是谱系之间功能互补性增加的结果(Cadotte,2013 年;Huang等人,2020 年)。事实上,许多研究表明,系统发育多样性比物种丰富度的衡量标准更能解释生态系统功能(生物量积累)、稳定性和群落生物量生产力(Coelho de Souza et al., 2019;Lasky等人,2014 年;Paquette et al., 2015;Potter & Woodall, 2014;Rodríguez-Hernández 等人。,2021 年;Satdichanh et al., 2018;Yuan等人,2020 年)并且优于功能多样性(Flynn et al., 2011;Larkin et al., 2015),基于相关性状在系统发育上是保守的假设(Coelho de Souza et al., 2016;Srivastava et al., 2012)。

在这里,我们使用了 1982 年在中非共和国建立的实验点来评估进化多样性在不同干扰背景下对森林生物量和生产力的影响。我们特别旨在 (1) 理清多样性对不同生物量成分的影响,以更好地了解不同的生态机制是否以及如何共同决定天然热带森林的多样性-生产力关系,以及 (2) 测试历史干扰是否影响多样性对生物量和生物量生产力的影响。我们预测了多样性对生物量生产力的影响在未受干扰的森林和受干扰的森林之间有所不同。在受干扰的森林中,由于少数资源获取和高效物种占据主导地位,压倒性的适应性差异可能会阻止互补性(Jucker et al., 2020;Reich et al., 2012;Tobner et al., 2016),而未受干扰的森林通常以更多样化的树木群落为特征,这些树木群落在资源有限的条件下竞争(Lohbeck, Poorter, et al., 2015;Pacala & Tilman,2001 年)。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号