Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-07-29 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14376 Inger K. de Jonge 1 , J. Hans C. Cornelissen 1 , Han Olff 2 , Matty P. Berg 1, 2 , Richard S. P. van Logtestijn 1 , Michiel P. Veldhuis 3

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Termites are ecologically significant organisms in tropical ecosystems, playing a crucial role in nutrient recycling and maintaining ecosystem functioning and productivity (Govorushko, 2019; Griffiths et al., 2019; Jouquet et al., 2006; Veldhuis et al., 2017). The subfamily Macrotermitinae, within the family Termitidae, comprises fungus-growing termites which have emerged as dominant decomposers of plant material throughout the savannas of the Old World (Aanen et al., 2002; Jones & Eggleton, 2011). These termites can harvest up to 30% of annual litter production in savanna ecosystems (Wood & Sands, 1978), paralleling the organic matter turnover by mammalian herbivores and fires that contribute roughly 20% of carbon mineralization in these ecosystems (Bignell & Eggleton, 2000). Besides their important roles in nutrient recycling and redistribution, fungus growers are considered soil physical engineers that improve soil fertility and aeration through bioturbation (Jouquet et al., 2011). However, human disturbance and land use changes are now affecting termite mound distribution, which can reduce the ecosystem services provided by fungus-growing termites in human-dominated areas (Davies et al., 2020). These activities, by intensifying herbivory and changing fire frequencies, also drive shifts in plant species composition, subsequently altering the availability and characteristics of litter that termites rely on.

Fungus-growing termites are commonly considered generalists, capable of exploiting various food resources, from wood to grass (da Costa et al., 2019; Krishna et al., 2013), potentially rendering them less sensitive to shifts in litter properties. However, this generalist view may oversimplify the complex feeding strategies and preferences underlying their success. The efficiency of fungus-growing termites in consuming low-quality and stoichiometrically imbalanced food sources stems from a specialized three-way symbiosis with their gut microbiome and a basidiomycete fungus (Brune, 2014; da Costa et al., 2019). Nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the gut enable these termites to utilize nitrogen efficiently, enhancing the nutritional quality of their diet (Sapountzis et al., 2016). Additionally, mechanisms such as selective respiration by the fungal comb help regulate the C:N ratio of collected substrates, demonstrating their specialized adaptations to thrive on poor-quality substrates (Higashi et al., 1992; Nobre et al., 2011). These adaptations suggest that selecting high-quality substrates (with low C:N ratios) might not be as critical for fungus-growing termites. Moreover, consuming substrates rich in sugars may lead to rapid fermentation in their gut, resulting in by-products that could harm their digestive system (Abe et al., 2000).

Contrary to the generalist label, experiments have shown that fungus-growing termites demonstrate a degree of selectivity (Smith et al., 2019) and indeed select low-nutrient substrates over high-nutrient substrates (Ouédraogo et al., 2004; Shanbhag et al., 2019; Sundsdal et al., 2020). Most studies on termite foraging patterns typically examined only two or three substrate types, for instance, contrasting elephant or cattle dung with straw. As a result, it is challenging to determine whether termites indeed favour lower-quality substrates or whether other chemical traits are important as well, and whether there is selectivity within the same type of organic substrate (e.g. among leaf litter differing in quality among species). Mammalian dung may not be the preferred substrate for fungus-growing termites due to the higher probability of encountering entomopathogenic fungi or bacteria in dung than in dry plant litter (Freymann et al., 2008). Termite nests are warm and humid, which should make them prone to infectious diseases. Interestingly, termite nests are exceptionally sterile environments (Otani et al., 2019), effectively protecting the Termitomyces monoculture termites rely on. This sterility is likely maintained through a range of behaviours aimed at reducing pathogen transmissions, such as grooming, nest cleaning, secretion of antibiotics, avoidance of substrates exposed to mycopathogens and colony relocation (Bodawatta et al., 2019; Roy et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2022). Consequently, it is plausible to suggest that termite substrate preferences may be influenced by factors beyond simple nutrient content, including the necessity to maintain nest sterility.

While the significance of variation in litter traits across species in decomposability is well-established (Canessa et al., 2021; Cornwell et al., 2008; Freschet et al., 2012; Makkonen et al., 2012), a current imperative lies in understanding how dominant groups of macrodetritivores, such as fungus-growing termites, contribute to the mass loss of different litter substrates. Macrodetritivore effects generally increase with aridity (Sagi & Hawlena, 2023). For example, fungus-growing termites can accelerate recycling rates by as much as 123% under water-limited conditions (Veldhuis et al., 2017), highlighting the need to investigate how specific litter traits influence their foraging activities.

Here, we performed a litter decomposition experiment in an African savanna that included 46 different substrate types (23 grass species, both leaf and stem litter), in litter bags, to understand how litter traits predict litter turnover, both through non-termite-assisted decomposition and through substrate removal by fungus-growing termites. We focus on two measures: relative mass loss of litter substrates and the phenomenon of ‘sheeting’. Sheeting, a behaviour commonly associated with fungus-growing termites in African savannas, involves creating a covering over litter substrates made from a mix of soil particles, saliva, and organic materials (Sileshi et al., 2010). This covering serves dual purposes: it acts as a protective barrier against UV radiation and modifies the microclimatic conditions around the litter, facilitating termite activity (Sileshi et al., 2010). It is crucial to note that while the presence of sheeting is a reliable indicator of termite presence, it does not directly equate to active termite foraging. Active foraging and litter removal is inferred from the observed changes in the mass loss of litter substrates. Therefore, in cases where sheeting is observed, any significant difference in mass loss between litter bags accessible to termites and those that are not can be confidently attributed to termite foraging activity. This distinction is important for understanding the termites' ecological role, particularly in how they select and process different litter substrates based on their traits.

Termite activity in litter decomposition may thus operate in two distinct phases: initial selection of the litter based on its traits, evident from the rates of sheeting, followed by the impact of these traits on the extent of mass loss post-colonization. Our research questions are therefore as follows: (1) What is the effect of litter traits on the percentage of sheeted litter bags (a measure of termite presence)? (2) How do litter traits affect mass loss of leaf and stem litter, both with and without the presence of fungus-growing termites? (3) How do litter traits influence the overall contribution of fungus-growing termites to litter mass loss, considering the combined effects of sheeting rates and differential mass loss between sheeted and unsheeted litter bags?

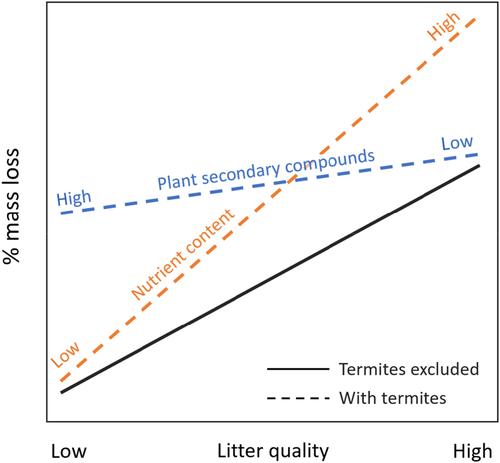

Based on our conceptual model (Figure 1), we propose three alternative hypotheses concerning the selectivity of fungus-growing termites in terms of interspecific variation in litter quality: (A) Fungus-growing termites do not preferentially select litter with high- or low-litter quality (with quality representing both nutrient content and plant secondary compounds). The added effect of termites on the mass loss of plant litter (on top of the effect of other soil-based decomposers on mass loss) is, therefore, equal across litter trait spectra. (B) Fungus-growing termites select litter with low quality, thereby ameliorating the well-established constraint of litter quality on decomposition by free-living soil microorganisms. (C) Fungus-growing termites select high-quality litter and thereby amplify the positive effects of nutrient-rich litter on mass loss.

中文翻译:

次要化合物可增加白蚁清除 23 种稀树草原草种的垃圾的能力

1 简介

白蚁是热带生态系统中具有重要生态意义的生物,在养分循环以及维持生态系统功能和生产力方面发挥着至关重要的作用(Govorushko, 2019 ;Griffiths等, 2019 ;Jouquet等, 2006 ;Veldhuis等, 2017 )。大白蚁亚科属于白蚁科,由生长真菌的白蚁组成,这些白蚁已成为整个旧世界稀树草原植物材料的主要分解者(Aanen 等人, 2002 年;Jones 和 Eggleton, 2011 年)。这些白蚁可以收获热带稀树草原生态系统中每年垃圾产量的 30%(Wood & Sands, 1978 ),与哺乳动物食草动物和火灾的有机物周转量相当,而火灾贡献了这些生态系统中约 20% 的碳矿化(Bignell & Eggleton, 2000) )。除了在养分循环和再分配方面发挥重要作用外,真菌种植者还被认为是土壤物理工程师,可以通过生物扰动提高土壤肥力和通气性(Jouquet et al., 2011 )。然而,人类干扰和土地利用变化现在正在影响白蚁丘的分布,这会减少人类主导地区真菌生长白蚁提供的生态系统服务(Davies et al., 2020 )。这些活动通过强化食草和改变火灾频率,也推动了植物物种组成的变化,从而改变了白蚁所依赖的垃圾的可用性和特征。

真菌生长的白蚁通常被认为是多面手,能够利用从木材到草的各种食物资源(da Costa 等人, 2019 年;Krishna 等人, 2013 年),这可能使它们对凋落物特性的变化不太敏感。然而,这种通才观点可能过于简单化了其成功背后的复杂喂养策略和偏好。真菌生长的白蚁消耗低质量和化学计量不平衡食物来源的效率源于其肠道微生物组和担子菌的特殊三向共生(Brune, 2014 ;da Costa 等, 2019 )。肠道中的固氮细菌使这些白蚁能够有效地利用氮,从而提高其饮食的营养质量(Sapountzis 等, 2016 )。此外,真菌梳的选择性呼吸等机制有助于调节所收集底物的碳氮比,证明它们能够在劣质底物上茁壮成长(Higashi 等人, 1992 ;Nobre 等人, 2011 )。这些适应性表明,选择高质量的基质(具有低碳氮比)对于真菌生长的白蚁来说可能并不那么重要。此外,食用富含糖的底物可能会导致肠道内快速发酵,产生可能损害消化系统的副产物(Abe et al., 2000 )。

与通才标签相反,实验表明,真菌生长的白蚁表现出一定程度的选择性(Smith 等, 2019 ),并且确实选择低营养基质而不是高营养基质(Ouédraogo 等, 2004 ;Shanbhag 等) ., 2019 ;Sundsdal 等人, 2020 )。大多数关于白蚁觅食模式的研究通常只检查两种或三种基质类型,例如,将大象或牛粪与稻草进行对比。因此,确定白蚁是否确实喜欢低质量基质或其他化学特性是否也很重要,以及同一类型的有机基质内是否存在选择性(例如,不同物种之间质量不同的落叶层)具有挑战性。 。哺乳动物粪便可能不是真菌白蚁生长的首选基质,因为与干燥植物垃圾相比,在粪便中遇到昆虫病原真菌或细菌的可能性更高(Freymann 等, 2008 )。白蚁巢穴温暖潮湿,这使得它们容易感染传染病。有趣的是,白蚁巢穴是异常无菌的环境(Otani et al., 2019 ),有效地保护了白蚁所依赖的单一栽培的Termitomyces 。这种不育性可能是通过一系列旨在减少病原体传播的行为来维持的,例如梳理、清理巢穴、分泌抗生素、避免暴露于真菌病原体的底物以及菌落迁移(Bodawatta等人, 2019年;Roy等人, 2006年)施密特等人, 2022 )。 因此,有理由认为,白蚁对基质的偏好可能受到简单营养成分以外的因素的影响,包括保持巢穴无菌的必要性。

虽然不同物种的凋落物性状在可分解性方面的差异的重要性已得到充分证实(Canessa 等人, 2021 年;Cornwell 等人, 2008 年;Freschet 等人, 2012 年;Makkonen 等人, 2012 年),但当前的当务之急是了解大型食腐动物的优势群体(例如生长真菌的白蚁)如何导致不同垫料基质的质量损失。大型食腐动物的影响通常会随着干旱而增加(Sagi & Hawlena, 2023 )。例如,在水资源有限的条件下,生长真菌的白蚁可以将回收率提高高达 123%(Veldhuis 等, 2017 ),这凸显了研究特定垃圾特征如何影响其觅食活动的必要性。

在这里,我们在非洲大草原上进行了一次凋落物分解实验,其中包括装在凋落物袋中的 46 种不同基质类型(23 种草类,包括叶和茎凋落物),以了解凋落物特征如何通过非白蚁辅助来预测凋落物周转。分解并通过生长真菌的白蚁去除基质。我们关注两个指标:垫料的相对质量损失和“片状”现象。覆盖是一种通常与非洲稀树草原真菌生长白蚁相关的行为,涉及在由土壤颗粒、唾液和有机材料的混合物制成的垃圾基质上形成覆盖物(Sileshi 等, 2010 )。这种覆盖物有双重用途:它充当紫外线辐射的保护屏障,并改变垃圾周围的小气候条件,促进白蚁活动(Sileshi 等人, 2010 )。值得注意的是,虽然白蚁的存在是白蚁存在的可靠指标,但它并不直接等同于活跃的白蚁觅食。从观察到的垫料质量损失的变化推断出主动觅食和垫料清除。因此,在观察到结片的情况下,白蚁可触及的垃圾袋与不可触及的垃圾袋之间质量损失的任何显着差异都可以确信归因于白蚁的觅食活动。这种区别对于理解白蚁的生态作用非常重要,特别是它们如何根据其特征选择和处理不同的垫料。

因此,枯枝落叶分解中的白蚁活动可能分两个不同的阶段进行:根据其特征(从片状覆盖率可以明显看出)对枯枝落叶进行初始选择,然后是这些特征对定殖后质量损失程度的影响。因此,我们的研究问题如下:(1)垃圾特征对片状垃圾袋的百分比(白蚁存在的衡量标准)有什么影响? (2) 无论是否存在真菌白蚁,凋落物性状如何影响叶和茎凋落物的质量损失? (3) 考虑到覆膜率和覆膜垃圾袋与未覆膜垃圾袋之间质量损失差异的综合影响,凋落物性状如何影响真菌生长白蚁对凋落物质量损失的总体贡献?

基于我们的概念模型(图 1),我们提出了关于真菌生长白蚁在垫料质量的种间变异方面的选择性的三种替代假设:(A)真菌生长白蚁不会优先选择具有高或低的垫料。凋落物质量(质量代表养分含量和植物次生化合物)。因此,白蚁对植物凋落物质量损失的附加影响(除了其他土壤分解剂对质量损失的影响之外)在凋落物性状谱中是相等的。 (B) 生长真菌的白蚁选择低质量的垫料,从而改善了垫料质量对自由生活的土壤微生物分解的既定限制。 (C) 生长真菌的白蚁选择高质量的垫料,从而放大营养丰富的垫料对质量损失的积极影响。

在图查看器PowerPoint中打开

显示真菌生长的白蚁如何导致质量或其他垃圾特征不同的垃圾大量损失的概念模型。答:除了通过自由生活的土壤微生物组的分解活动(黑色实线)造成质量损失的影响之外,白蚁还同样加速了所有垃圾类型的质量损失(黑色虚线)。 B:白蚁选择低质量的垫料,从而解除了低质量垫料对质量损失的限制(蓝色虚线)。 C:白蚁选择高质量的垫料,从而放大高质量垫料对质量损失的积极影响(橙色虚线)。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号