Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-07-21 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14373 Julia Dieskau 1, 2 , Isabell Hensen 1, 2 , Nico Eisenhauer 2, 3 , Ingmar Gaberle 1 , Walter Durka 2, 4 , Susanne Lachmuth 1, 5 , Harald Auge 2, 4

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Intraspecific and interspecific plant–plant interactions affect the assembly of plant communities in complex and diverse ways (Chase, 2003a; Fukami, 2015; Götzenberger et al., 2012; HilleRisLambers et al., 2012; Larson & Funk, 2016; Rolhauser & Pucheta, 2017). Among other factors, the timing and order of species arrival appears to play a significant role in the outcome of community assembly processes and previous studies investigated these so-called ‘priority effects’ in a wide range of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (Chase, 2003b; Dunck et al., 2021; Fukami et al., 2010; Klingbeil & Willig, 2016; Toju et al., 2018). However, despite a strongly increasing interest in priority effects, they continue to be an underrepresented topic in community assembly research (Fukami, 2015). In this study, we follow a broad definition of priority effects as the impact of an early-arriving species on a late-arriving species, occasionally referred to as historical contingency (Fukami, 2015; Zou & Rudolf, 2023). However, we are aware of other, narrower definitions according to Modern Coexistence Theory, which reserves the term for cases in which the outcome of species interactions depends on the order of arrival (Grainger et al., 2019; Ke & Letten, 2018).

The net effect of the early-arriving plant on the late-arriving plant can be positive, neutral or negative and is based on a variety of mechanisms. First, early-arriving species can change the biotic and abiotic environmental conditions (Connell & Slatyer, 1977; Debray et al., 2022), for example, through the microclimate they create or through plant–soil feedbacks, where one plant species alters the soil conditions in a way that induces feedback on the performance of the species itself and/or on other species (Delory et al., 2021; Grman & Suding, 2010; Heinen et al., 2020). Second, the previous reduction of shared resources by the early-arriving species (space, nutrients, light, water, etc.) can lead to asymmetric competition, both above-ground and below-ground (Körner et al., 2008; Weidlich et al., 2017) and hamper the establishment, survival, productivity and reproduction of the late-arriving species.

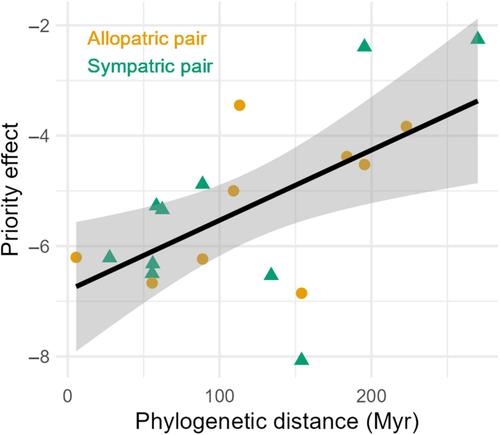

As evolutionary relationships have been generally shown to play an important role in the outcome of species interactions, they might be a helpful predictor of the strength of priority effects. The competition relatedness hypothesis (Cahill et al., 2008) states that closely related species compete more intensely with each other than with distantly related competitors and goes back to Darwin's observation that ‘the struggle will generally be more severe between species of the same genus, when they come into competition with each other than between species of distinct genera’ (Darwin, 1859). This assumption has been supported by many studies (reviewed by Dayan & Simberloff, 2005). One mechanism behind this phenomenon may be that closely related species are ecologically more similar and therefore have more similar niches, resulting in stronger priority effects among species with higher resource use overlap (Vannette & Fukami, 2014). Considering Chase and Leibold's (2003, p. 15) definition of a niche, the strength of competition for resources should increase with niche similarity, ultimately decreasing the probability of closely related species to coexist, as predicted by the limiting similarity hypothesis (MacArthur & Levins, 1967). As ecologically relevant traits have been shown to often be phylogenetically conserved (Prinzing et al., 2001; Wiens et al., 2018), phylogenetic distances (PDs) between higher plants can indicate their ecological differences and allow predictions about their interactions. However, although many studies found a clear association between PD and the outcome of species interactions (Cadotte, 2013; Germain et al., 2016; Sheppard et al., 2018; Verdú et al., 2012; Violle et al., 2011), others did not (Cahill et al., 2008; Fitzpatrick et al., 2017; Fritschie et al., 2014; Godoy et al., 2014; Narwani et al., 2013). These contradictory results might be caused by a number of biological and methodological factors such as inappropriate phylogenies, skewed distributions of PDs, absence of sufficient niche spaces or ignoring models of trait evolution (reviewed in Cadotte et al., 2017).

Studies testing the importance of phylogenetic relationships in priority effects are rare, and so far show no clear trend either. Although studies involving other organisms, such as yeast species in the floral nectar of shrubs (Peay et al., 2011) or bacteria (Tan et al., 2012), have often found that priority effects are stronger between closer relatives, the results of studies in plants are less clear. Castro et al. (2014), for example, carried out a set of manipulative experiments in which they controlled the PD of a colonising species (Lactuca sativa) with five assemblages of plants (the recipient communities) and found that neither the mean PD between Lactuca and the members of each assemblage nor the mean PD to the nearest neighbour affected the performance of the late-arriving plants (germination, growth, flowering, survival and Lactuca recruitment). Sheppard et al. (2018) found that the success of the establishment of recently introduced species in permanent grasslands throughout France was positively affected by the phylogenetic relatedness to native species and previous invaders.

One reason why phylogenies do not always predict ecological differences among species is that sympatric species may have evolved trait differences fostering coexistence, which can override phylogenetic effects (Cadotte et al., 2017). Thus, the effect of PD on priority effects might depend on the biogeographic history (BH) of early- and late-arriving species. While allopatric species did not have the opportunity to interact with each other because of geographic or habitat barriers, co-occurring sympatric species may have competed for the same resources in the past. Such interspecific competition can influence evolutionary trajectories through selection for greater niche divergence (Brown & Wilson, 1956; Schluter, 2000; Silvertown, 2004; Symonds & Elgar, 2004; Tobias et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2016) and, as a consequence, even closely related species can differ substantially and show larger niche difference than expected based on their phylogeny (Davies et al., 2007; Nuismer & Harmon, 2015; Schluter, 1994; Staples et al., 2016). How a history of sympatry can lead to evolutionary changes in species traits that increase niche differentiation has been previously discussed on an intraspecific level (e.g. Aarssen & Turkington, 1985; Hart et al., 2019; Sakarchi & Germain, 2023) as well as on an interspecific level (e.g. Germain et al., 2016; Thorpe et al., 2011).

Furthermore, the role of PD for the strength of priority effects could also differ for different life cycle components of the late-arriving plants (for simplicity, referred to as life stage hereafter). Unfortunately, the seedling stage is often ignored in trait-based analyses (Larson & Funk, 2016), and evidence for phylogenetic signal in seedling traits is not unequivocal (Husáková et al., 2018). However, seedlings may have environmental requirements and thus niches distinct from those of conspecific adults due to ontogenetic niche shifts (Lyons & Barnes, 1998; Miriti, 2006; Müller et al., 2018; Parish & Bazzaz, 1985). Therefore, the importance of phylogeny for the priority effect should increase as late-arriving species mature from the seedling stage to the adult stage, whereby closely related species become ecologically more similar to the adult early-arriving species.

However, we are not aware of any studies investigating the influence of BH and the life stage (LS) of late-arriving species on the impact of PD on priority effects. To address this critical knowledge gap, we conducted a greenhouse study that investigated the role of PD for the priority effect of an early-arriving species on the establishment and performance of a late-arriving species. To analyse the influence of BH, we used interactions with 10 allopatric pairs (i.e. early-arriving species exotic and late-arriving species native to Germany) and 10 sympatric pairs (i.e. early- and late-arriving species native to Germany) of biennial and perennial European grassland species of different families and functional groups, spanning a gradient of PD. We tested the following hypotheses: (1) The priority effect of an early-arriving plant on a late-arriving plant of another species increases with decreasing PD between them due to higher ecological similarity. (2) The importance of PD for priority effects is more pronounced in allopatric than in sympatric species pairs as co-occurring closely related species have evolved niche differences which reduce competition. (3) The significance of PD for priority effects increases, as closely related late-arriving plants age, and become more ecologically similar to early-arriving adult plants.

中文翻译:

系统发育关系和植物生命阶段而不是生物地理学历史介导欧洲草原植物的优先效应

1 简介

种内和种间植物间相互作用以复杂多样的方式影响植物群落的组装(Chase, 2003a ;Fukami, 2015 ;Götzenberger 等, 2012 ;HilleRisLambers 等, 2012 ;Larson & Funk, 2016 ;Rolhauser & Pucheta) , 2017 )。除其他因素外,物种到达的时间和顺序似乎对群落组装过程的结果起着重要作用,之前的研究调查了广泛的陆地和水生生态系统中的这些所谓的“优先效应”(Chase, 2003b ; Dunck 等人, 2021 ;Fukami 等人, 2010 ;Toju 等人, 2018 ;然而,尽管人们对优先效应的兴趣日益浓厚,但它们仍然是社区集会研究中代表性不足的主题(Fukami, 2015 )。在本研究中,我们遵循优先效应的广泛定义,即早到物种对晚到物种的影响,有时称为历史偶然事件(Fukami, 2015 ;Zou&Rudolf, 2023 )。然而,我们知道根据现代共存理论还有其他更狭义的定义,该理论保留了物种相互作用的结果取决于到达顺序的情况的术语(Grainger 等人, 2019 年;Ke & Letten, 2018 年)。

早到植物对晚到植物的净影响可以是积极的、中性的或消极的,并且基于多种机制。首先,早期到达的物种可以改变生物和非生物环境条件(Connell & Slatyer, 1977 ;Debray et al., 2022 ),例如,通过它们创造的小气候或通过植物-土壤反馈,其中一种植物物种改变了生物和非生物环境条件。以某种方式诱导对物种本身和/或其他物种的表现的反馈(Delory 等人, 2021 ;Grman 和 Suding, 2010 ;Heinen 等人, 2020 )。其次,先前到达的物种(空间、养分、光、水等)共享资源的减少可能导致地上和地下的不对称竞争(Körner等人, 2008年;Weidlich等人) al., 2017 )并阻碍了晚到物种的建立、生存、生产力和繁殖。

由于进化关系通常被证明在物种相互作用的结果中发挥着重要作用,因此它们可能有助于预测优先效应的强度。竞争相关性假说(Cahill et al., 2008 )指出,亲缘关系密切的物种之间的竞争比亲缘关系较远的竞争者之间的竞争更加激烈,这可以追溯到达尔文的观察,即“同一属的物种之间的竞争通常会更加激烈,当它们相互竞争而不是不同属的物种之间竞争时”(达尔文, 1859 )。这一假设得到了许多研究的支持(由 Dayan 和 Simberloff 审查, 2005 年)。这种现象背后的一个机制可能是密切相关的物种在生态上更加相似,因此具有更多相似的生态位,从而导致资源利用重叠程度较高的物种之间的优先效应更强(Vannette&Fukami, 2014 )。考虑到 Chase 和 Leibold( 2003 年,第 15 页)对生态位的定义,对资源的竞争强度应该随着生态位的相似性而增加,最终降低密切相关的物种共存的可能性,正如极限相似性假设所预测的那样(麦克阿瑟和莱文斯) , 1967 )。由于生态相关性状已被证明通常在系统发育上是保守的(Prinzing et al., 2001 ;Wiens et al., 2018 ),高等植物之间的系统发育距离(PD)可以表明它们的生态差异并允许预测它们的相互作用。 然而,尽管许多研究发现PD与物种相互作用的结果之间存在明显的关联(Cadotte, 2013 ;Germain等, 2016 ;Sheppard等, 2018 ;Verdú等, 2012 ;Violle等, 2011 ) ,其他人则没有(Cahill 等人, 2008 ;Fitzpatrick 等人, 2017 ;Fritschie 等人, 2014 ;Godoy 等人, 2014 ;Narwani 等人, 2013 )。这些矛盾的结果可能是由许多生物学和方法学因素引起的,例如不适当的系统发育、PD分布不均、缺乏足够的生态位空间或忽略性状进化模型(Cadotte等人综述, 2017 )。

测试系统发育关系在优先效应中的重要性的研究很少,而且迄今为止也没有显示出明显的趋势。尽管涉及其他生物体的研究,例如灌木花蜜中的酵母物种(Peay等, 2011 )或细菌(Tan等, 2012 ),经常发现近亲之间的优先效应更强,但对植物的研究还不太清楚。卡斯特罗等人。例如,( 2014 )进行了一系列操作性实验,其中他们控制了具有五个植物组合(接收群落)的定殖物种( Lactuca sativa )的PD,发现Lactuca和成员之间的平均PD每个组合的平均PD或到最近邻居的平均PD都会影响晚到植物的性能(发芽、生长、开花、存活和莴苣补充)。谢泼德等人。 ( 2018 )发现,最近引进的物种在法国各地永久草原上的成功建立受到与本地物种和先前入侵者的系统发育相关性的积极影响。

系统发育并不总能预测物种之间的生态差异的原因之一是,同域物种可能进化出了促进共存的性状差异,这可以克服系统发育效应(Cadotte et al., 2017 )。因此,PD对优先效应的影响可能取决于早期和晚期到达物种的生物地理历史(BH)。虽然异域物种由于地理或栖息地障碍而没有机会相互影响,但共生的同域物种在过去可能会竞争相同的资源。这种种间竞争可以通过选择更大的生态位分歧来影响进化轨迹(Brown & Wilson, 1956 ;Schluter, 2000 ;Silvertown, 2004 ;Symonds & Elgar, 2004 ;Tobias et al., 2014 ;Weber et al., 2016 ),因此,即使是密切相关的物种也可能存在很大差异,并且根据其系统发育表现出比预期更大的生态位差异(Davies et al., 2007 ;Nuismer & Harmon, 2015 ;Schluter, 1994 ;Staples et al., 2016 )。同源历史如何导致物种性状的进化变化,从而增加生态位分化,之前已经在种内水平上进行了讨论(例如Aarssen&Turkington, 1985 ;Hart等人, 2019 ;Sakarchi&Germain, 2023 )以及种间水平(例如 Germain 等人, 2016 ;Thorpe 等人, 2011 )。

此外,对于晚到植物的不同生命周期组成部分(为简单起见,以下称为生命阶段),PD 对优先效应强度的作用也可能有所不同。不幸的是,在基于性状的分析中,幼苗阶段经常被忽视(Larson & Funk, 2016 ),并且幼苗性状中系统发育信号的证据并不明确(Husáková et al., 2018 )。然而,幼苗可能有环境要求,因此由于个体发育生态位的变化,其生态位不同于同种成虫的生态位(Lyons & Barnes, 1998 ;Miriti, 2006 ;Müller et al., 2018 ;Parish & Bazzaz, 1985 )。因此,随着晚到物种从幼苗阶段成熟到成虫阶段,系统发育对于优先效应的重要性应该增加,从而密切相关的物种在生态上变得与成虫早到物种更加相似。

然而,我们不知道有任何研究调查 BH 和晚到物种的生命阶段 (LS) 对 PD 对优先效应的影响。为了解决这一关键的知识差距,我们进行了一项温室研究,调查了 PD 对早到达物种的优先影响对晚到达物种的建立和表现的作用。为了分析 BH 的影响,我们使用了 10 个异域对(即早到的外来物种和晚到的德国本土物种)和 10 个同域对(即早到和晚到的德国本土物种)的相互作用。多年生欧洲草原物种的不同科和功能类群,跨越PD梯度。我们测试了以下假设:(1)由于生态相似性较高,早到植物对另一物种晚到植物的优先效应随着它们之间的 PD 降低而增加。 (2) PD 对优先效应的重要性在异域物种对中比在同域物种对中更为明显,因为共生的密切相关物种已经进化出生态位差异,从而减少了竞争。 (3)随着晚到植物年龄密切相关,并且在生态上与早到成年植物更加相似,PD对优先效应的重要性增加。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号