Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-07-08 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14368 Mario B. Pesendorfer 1 , Michał Bogdziewicz 2 , Iris Oberklammer 1 , Ursula Nopp‐Mayr 3 , Jerzy Szwagrzyk 4 , Georg Gratzer 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

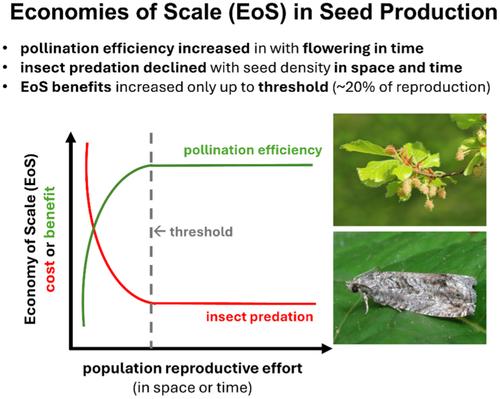

In temperate Europe, many stand-dominating tree species present considerable variation in interannual fruiting (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2017; Pesendorfer et al., 2020). Such temporally variable and spatially synchronized seed production in plant populations, called masting, is thought to provide individuals fitness benefits associated with economies of scale (hereafter “EOS”), which decrease the cost of reproduction per surviving offspring with increasing extent of seed production (Norton & Kelly, 1988; Pearse et al., 2016). On a proximate level, masting is thought to arise from the interplay between annual weather conditions and resource dynamics before and during flowering and fructification (Crone & Rapp, 2014; Pearse et al., 2016). In mast-seeding, two density-dependent mechanisms (hereafter “DD”) that result in EOS are reduced pollen limitation in years of extensive flowering and satiation of seed predators in years of bumper crops (Kelly & Sork, 2002). In species in which these mechanisms operate, recruitment of seedlings peaks after mast years, when higher pollination efficiency during mass flowering increases relative seed viability and pre- and post-dispersal seed predators are satiated (Clark et al., 1998; Crawley & Long, 1995; Zwolak et al., 2016, 2022). However, patterns of seed production are changing worldwide in response to climate change (Clark et al., 2021; Pearse et al., 2017; Shibata et al., 2020). For the many species that regenerate through masting, these changes include altered synchrony and interannual variation in seed production, which can all affect reproduction success if EOS determine plant regeneration, population dynamics and community structure (Bogdziewicz, Ascoli, et al., 2020; Pearse et al., 2017; Shibata et al., 2020). We thus need to understand whether mechanisms that result in EOS operate across plant species to assess how changes in reproductive patterns may affect plant fitness and regeneration. Despite rising interest in mast-seeding and its proximate and ultimate mechanisms (Koenig, 2021; Pesendorfer et al., 2021), the relative contributions of different EOS mechanisms and their potential interactions have received less attention (but see Zwolak et al., 2022). Here, we use a long-term dataset of high spatial resolution to investigate how pollen limitation and predispersal predation vary with spatiotemporal differences in seed production in Central Europe's few remaining old-growth montane forests.

The pollination efficiency hypothesis suggests that when pollen is limiting, for example due to low productivity or conspecific density, increased pollination success in high flowering years selects for mast-seeding (Kelly et al., 2001), providing the highest fitness to temporally variable and spatially synchronous trees (Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020). While the role of pollen limitation in driving reproduction of wind-pollinated plants was long underestimated (Koenig & Ashley, 2003), a series of studies mostly based in North America and New Zealand found that pollination efficiency correlated positively with flowering density, thus supporting the hypothesis (Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020; Houle, 1999; Kelly et al., 2001; Moreira et al., 2014; Norton & Kelly, 1988; Rapp et al., 2013; Smith et al., 1990). In European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), density-dependent pollen limitation was found when correlating the proportion of hollow, unpollinated seeds with stand size across a Swedish landscape; trees in larger stands had a higher proportion of viable seeds (Nilsson & Wastljung, 1987). Similarly, across England, F. sylvatica trees that are more responsive to temperature variation and thus more synchronous with their respective populations have lower proportions of unfertilized seeds (Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020). However, it is unclear to what extent the pollination-efficiency EOS occurs across European forest trees. While pollination dynamics are an important driver of fruiting dynamics in oaks where weather conditions during and after flowering play an important role in driving the extent of reproduction (Bogdziewicz et al., 2017; Fleurot et al., 2023; Koenig et al., 2012, 2015; Schermer et al., 2019), pollination efficiency is not always affected by masting. For example, pollen limitation was not affected by interannual variation in flowering in Sorbus aucuparia L. or in Aciphylla squarrosa J.R. Forst. & G. Forst, two insect-pollinated species where pollinators, rather than pollen, are likely limiting (Pías & Guitián, 2006; Brookes & Jesson, 2007). Similarly, in self-compatible species that do not rely on external pollen sources, masting has no effect on pollination efficiency (Kelly & Sullivan, 1997). Furthermore, intraspecific variation in masting behaviour and its underlying mechanisms has been observed in several species (Fleurot et al., 2023; Nussbaumer et al., 2018) and is therefore unclear whether pollination EOS occur across the ranges of species.

The predator satiation hypothesis proposes that seed predators are satiated by bumper crops (“mast years”) so that seeds show higher survival than in years of lower reproduction (Kelly & Sork, 2002; Zwolak et al., 2022). Predator satiation is thought to be particularly effective when the mast year is preceded by a low-reproduction year, and the demographic response by the predator reduces the population (Kelly & Sullivan, 1997; Zwolak et al., 2022). Mast seeding has been shown to reduce proportional insect seed predation in several temperate European forest trees, including Fagus sylvatica (Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020; Nilsson & Wastljung, 1987), Quercus robur L. (Crawley & Long, 1995; Gurnell, 1993), Larix decidua Mill. (Poncet et al., 2009) and Sorbus aucuparia (Kobro et al., 2003; Seget et al., 2022). However, insect predators are not always satiated by mast seeding. For example, large seed crops can result in a bottom-up, aggregative effect on the insect population that effectively cancels predator satiation (Bogdziewicz, Espelta, et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2001). Similar responses were found for small mammals with fast increases of rodent densities largely driven by seed availability in mast years (Sachser et al., 2021), leading to low seed survival at experimental dishes and in natural populations (Nopp-Mayr et al., 2012).

Moreover, masting does not satiate insects if they synchronize their life cycle with periodical seed production (Kelly et al., 2000; Maeto & Ozaki, 2003). Mobile predators may even be attracted to large seed crops and consume relatively more seeds than they would otherwise, thereby selecting against masting (Curran & Leighton, 2000; Koenig et al., 2003). Some species can also sustain themselves on alternate food sources during low seed years, avoiding starvation and numerical reduction, and return to seeds of interest as they become increasingly available (Bogdziewicz, Marino, et al., 2018; Fletcher et al., 2010). Predator satiation benefits of EOS may therefore not be universal, but rather context- and species-dependent (Zwolak et al., 2022).

While a majority of EOS research in masting addresses the effects of population-wide interannual variation of reproduction, spatial variation within a year can also affect seed viability and fate. The classic study by Nilsson and Wastljung (1987), for example, shows that low local abundance of European beech conspecifics can result in pollen limitation and increased seed predation. Similarly, Pesendorfer and Koenig (Pesendorfer & Koenig, 2016) found that valley oaks (Quercus lobata) with larger seed crops attracted more avian seed dispersers, which also distributed seeds at higher per-capita rates than from trees with small acorn crops in the same year. Positive density-dependence may therefore operate both on spatial and temporal variation in reproduction, depending on the underlying biological mechanism which would ultimately also select for reproductive synchrony and variability (Ascoli et al., 2021). Even at small scales, spatial variation in seed rain can affect tree recruitment of seedlings and saplings (Gratzer et al., 2022). Therefore, a concurrent investigation of spatial and temporal density-dependence in pollination efficiency and predator satiation will provide new insights into their effects on seed viability and fate (Beck et al., 2024).

We investigated the effect of temporal and spatial variation in reproductive effort on EOS mediated by density-dependent mechanisms in three species, European beech (Fagus sylvatica), Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst) and silver fir (Abies alba Mill.), that co-occur in a montane old-growth forest. Specifically, we explored how pollen limitation and predispersal predation vary in time and space using a 14-year, high-resolution dataset on seed production, seed predation and pollen limitation for two study plots with different relative densities of the three species. Based on these differences, we hypothesized that pollen limitation would vary systematically with temporal but not spatial variation in reproduction in the species with high density (beech), while it would vary in both dimension in the two species that occur at low density, particularly in the “JO” study plot where both conifers are scarce. In contrast, we hypothesized that predispersal predation of seeds by insects would correlate negatively with seed abundance in both time and space, and that this effect would increase with the abundance of the species, due to larger seed predator populations. Therefore, we predicted stronger effects in beech than in spruce and fir.

中文翻译:

积极的空间和时间密度依赖性驱动欧洲古老森林群落中肥大的早期繁殖规模经济效应

1 简介

在欧洲温带,许多林分优势树种的年际结果存在相当大的差异(Fernández-Martínez 等, 2017 ;Pesendorfer 等, 2020 )。植物种群中这种时间上可变且空间上同步的种子生产(称为肥育)被认为可以为个体提供与规模经济(以下简称“EOS”)相关的适应性效益,随着种子生产范围的增加,每个幸存后代的繁殖成本会降低。诺顿和凯利, 1988 ;皮尔斯等人, 2016 )。在近似水平上,肥大被认为是由开花和结果之前和期间的年度天气条件和资源动态之间的相互作用引起的(Crone&Rapp, 2014 ;Pearse等人, 2016 )。在肥大播种中,导致 EOS 的两种密度依赖机制(以下简称“DD”)是在大面积开花年份减少花粉限制,以及在丰收年份种子捕食者饱足(Kelly & Sork, 2002 )。在这些机制发挥作用的物种中,幼苗的补充在肥大年之后达到高峰,此时大量开花期间较高的授粉效率增加了种子的相对活力,并且传播前和传播后的种子捕食者得到了满足(Clark 等人, 1998 ;Crawley 和 Long, 1995 ;兹沃拉克等人,2016,2022 ) 。然而,为了应对气候变化,全球种子生产模式正在发生变化(Clark 等人, 2021 ;Pearse 等人, 2017 ;Shibata 等人, 2020 )。 对于通过肥大再生的许多物种来说,这些变化包括种子生产的同步性改变和年际变化,如果 EOS 决定植物再生、种群动态和群落结构,这些变化都会影响繁殖成功(Bogdziewicz、Ascoli 等, 2020 ;Pearse)等人, 2017 ;柴田等人, 2020 )。因此,我们需要了解导致 EOS 的机制是否在植物物种中发挥作用,以评估繁殖模式的变化如何影响植物的适应性和再生。尽管人们对桅杆播种及其近似和最终机制的兴趣日益浓厚(Koenig, 2021 ;Pesendorfer 等人, 2021 ),但不同 EOS 机制的相对贡献及其潜在相互作用受到的关注较少(但参见 Zwolak 等人, 2022 ) )。在这里,我们使用高空间分辨率的长期数据集来研究中欧仅存的少数古老山地森林中花粉限制和传播前捕食如何随种子生产的时空差异而变化。

授粉效率假说表明,当花粉受到限制时,例如由于生产力低或同种密度,在高开花年份增加授粉成功率会选择肥大播种(Kelly等人, 2001 ),为时间变化和同种密度提供最高的适应性。空间同步树(Bogdziewicz、Kelly 等人, 2020 )。虽然花粉限制在驱动风授粉植物繁殖中的作用长期以来被低估(Koenig & Ashley, 2003 ),但主要基于北美和新西兰的一系列研究发现,授粉效率与开花密度呈正相关,从而支持了假设(Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020 ;Houle, 1999 ;Kelly et al., 2001 ;Moreira et al., 2014 ;Norton & Kelly, 1988 ;Rapp et al., 2013 ;Smith et al., 1990 ) 。在欧洲山毛榉( Fagus sylvatica L.)中,当将瑞典景观中空心、未授粉种子的比例与林分大小相关联时,发现了密度依赖性花粉限制;林分较大的树木具有较高比例的可存活种子(Nilsson & Wastljung, 1987 )。同样,在英格兰各地,对温度变化更敏感的F. sylvatica树,因此与其各自的种群更加同步,未受精种子的比例较低(Bogdziewicz、Kelly 等人, 2020 )。然而,目前尚不清楚欧洲森林树木的授粉效率 EOS 在多大程度上发生。 虽然授粉动态是橡树结果动态的重要驱动因素,但开花期间和开花后的天气条件在驱动繁殖程度方面发挥着重要作用(Bogdziewicz 等人, 2017 年;Fleurot 等人, 2023 年;Koenig 等人, 2012 年) , 2015 ;Schermer 等人, 2019 ),授粉效率并不总是受到桅杆的影响。例如,花粉限制不受Sorbus aucuparia L. 或Aciphylla squarrosa JR Forst 开花年际变化的影响。 & G. Forst,两种昆虫授粉的物种,其中传粉媒介而不是花粉可能会受到限制(Pías & Guitián, 2006 ;Brookes & Jesson, 2007 )。同样,在不依赖外部花粉源的自交亲和物种中,肥大对授粉效率没有影响(Kelly&Sullivan, 1997 )。此外,在多个物种中观察到了肥大行为及其潜在机制的种内变异(Fleurot et al., 2023 ;Nussbaumer et al., 2018 ),因此尚不清楚授粉 EOS 是否发生在整个物种范围内。

捕食者饱和假说提出,种子捕食者会因丰收(“肥大年份”)而得到满足,因此种子比繁殖率较低的年份表现出更高的存活率(Kelly & Sork, 2002 ;Zwolak 等, 2022 )。当肥大年之前是低繁殖年时,捕食者的饱足感被认为特别有效,并且捕食者的人口反应会减少种群数量(Kelly&Sullivan, 1997 ;Zwolak等人, 2022 )。肥大播种已被证明可以减少欧洲几种温带林木中昆虫种子的捕食比例,包括水青冈(Bogdziewicz, Kelly, et al., 2020 ; Nilsson & Wastljung, 1987 )、 Quercus robur L. (Crawley & Long, 1995 ; Gurnell, 1993 ),落叶松落叶磨机。 (Poncet 等人, 2009 )和Sorbus aucuparia (Kobro 等人, 2003 ;Seget 等人, 2022 )。然而,昆虫捕食者并不总是满足于肥大播种。例如,大种子作物会对昆虫种群产生自下而上的聚合效应,从而有效地消除捕食者的饱足感(Bogdziewicz、Espelta 等人, 2018 年;Kelly 等人, 2001 年)。对于小型哺乳动物也发现了类似的反应,啮齿动物密度快速增加主要是由肥大年份的种子可用性驱动的(Sachser 等人, 2021),导致实验培养皿和自然种群中的种子存活率较低(Nopp-Mayr 等人,2021 )。 2012 )。

此外,如果昆虫将其生命周期与定期种子生产同步,则肥大不会使昆虫感到满足(Kelly 等人, 2000 年;Maeto 和 Ozaki, 2003 年)。移动捕食者甚至可能被大型种子作物所吸引,并比其他情况下消耗相对更多的种子,从而选择不进行捕食(Curran & Leighton, 2000 ;Koenig 等, 2003 )。一些物种还可以在种子匮乏的年份依靠替代食物来源维持生存,避免饥饿和数量减少,并随着种子变得越来越容易获得而返回到感兴趣的种子(Bogdziewicz、Marino 等人, 2018 年;Fletcher 等人, 2010 年) 。因此,EOS 的捕食者饱足益处可能不是普遍的,而是取决于环境和物种(Zwolak 等人, 2022 )。

虽然大多数关于肥大的 EOS 研究都解决了种群繁殖的年际变化的影响,但一年内的空间变化也会影响种子的活力和命运。例如,Nilsson 和 Wastljung( 1987 )的经典研究表明,欧洲山毛榉同种物种的局部丰度较低会导致花粉限制和种子捕食增加。同样,Pesendorfer 和 Koenig (Pesendorfer & Koenig, 2016 ) 发现,种子作物较大的山谷橡树 ( Quercus lobata ) 吸引了更多的鸟类种子传播者,其人均种子传播率也高于相同地区种子作物较小的树木。年。因此,正密度依赖性可能对生殖的空间和时间变化起作用,这取决于最终也会选择生殖同步性和变异性的潜在生物机制(Ascoli et al., 2021 )。即使在小尺度上,种子雨的空间变化也会影响幼苗和树苗的树木补充(Gratzer et al., 2022 )。因此,同时研究授粉效率和捕食者饱足感的空间和时间密度依赖性将为它们对种子活力和命运的影响提供新的见解(Beck等人, 2024 )。

我们研究了欧洲山毛榉 ( Fagus sylvatica )、挪威云杉 ( Picea abies (L.) H. Karst) 和银杉 ( Abies alba)三个物种中繁殖努力的时间和空间变化对由密度依赖机制介导的 EOS 的影响。 Mill.),共同出现在山地原始森林中。具体来说,我们使用 14 年高分辨率的种子生产、种子捕食和花粉限制数据集,针对三个物种具有不同相对密度的两个研究地块,探讨了花粉限制和传播前捕食如何随时间和空间变化。基于这些差异,我们假设花粉限制会随着高密度物种(山毛榉)繁殖的时间变化而不是空间变化而系统性地变化,而在低密度物种中,花粉限制会在两个维度上发生变化,特别是在“JO”研究样地,两种针叶树均稀少。相反,我们假设昆虫对种子的传播前捕食与时间和空间上的种子丰度呈负相关,并且由于种子捕食者种群规模较大,这种效应将随着物种的丰度而增加。因此,我们预测山毛榉的影响比云杉和冷杉的影响更强。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号