Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-07-04 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14365 Felipe E. Albornoz 1, 2, 3 , Suzanne M. Prober 3, 4 , Andrew Bissett 5 , Mark Tibbett 3, 6 , Rachel J. Standish 2

|

1 INTRODUCTION

To help reverse the rapid decline in biodiversity and ecosystems world-wide, the Convention on Biological Diversity adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, aiming to ‘ensure that by 2030 at least 30% of areas of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and marine and coastal ecosystems are under effective restoration’ (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022). To optimise restoration outcomes, we must first understand the mechanisms impeding recovery. Exotic plants and nutrient enrichment are often important limits to recovery (Corbin & D'Antonio, 2012), and these are often inter-related (Standish et al., 2006). Thus, restoration efforts that address plant–soil feedbacks between exotic plants and abiotic and biotic soil legacies may increase chances of success (Eviner & Hawkes, 2008).

Biotic soil legacies can include changes in the abundance and composition of beneficial soil microorganisms such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are plant mutualists that can increase plant phosphorus (P) and water uptake (Smith & Read, 2010), offer pathogen defence (Veresoglou & Rillig, 2012), improve soil physicochemical properties (Willis et al., 2013) and contribute to nutrient cycling (Powell & Rillig, 2018). They are a key component of ecosystem health, and the re-introduction of native AMF has been shown to promote vegetation recovery after degradation (Neuenkamp et al., 2019).

Nutrient enrichment is a form of degradation in native ecosystems, whereby soils become nutrient-enriched compared with their inherent levels. This can occur, for example, through fertilisation, global nitrogen (N) deposition or release of nutrients from disturbed vegetation, often leading to exotic plant invasions and loss of native diversity (Prober & Wiehl, 2012). These changes can be associated with the loss of key AMF or the arrival of ‘weedy’ AMF, both of which in turn may impede ecosystem recovery (Albornoz et al., 2023). We define ‘weedy AMF’ as those that arrive and persist in, or are promoted in degraded ecosystems, regardless of whether they are native or exotic.

It has been proposed that soil and plant N:P stoichiometry could determine the effect of nutrient enrichment on AMF (Johnson et al., 2013), based on Liebig's law of the minimum (von Liebig 1840). If native ecosystems are naturally P-limited or P and N co-limited, N enrichment is expected to exacerbate P limitation, potentially increasing the reliance of plants on their symbionts and promoting AMF. Alternatively, in ecosystems where P is readily available and N is limiting, N enrichment should alleviate plant nutrient co-limitation, potentially decreasing the plant's need to allocate carbon (C) to AMF (Johnson et al., 2013). Accordingly, in a global study of 25 grasslands, Leff et al. (2015) showed that N and P fertilisation decreased AMF relative abundance. Under high levels of N and P availability, plant diversity also decreases (Seabloom et al., 2021), potentially further limiting AMF due to low host diversity.

In extremely P-poor ecosystems, the proportion of non-AMF plant species tends to be higher due to the competitive advantage of other P-acquisition strategies that have evolved on these infertile soils (Lambers et al., 2011), potentially reducing host diversity and abundance for AMF. Hence, plant invasions, promoted by N enrichment, can increase host availability, further promoting AMF. In a recent study, for example, we showed that N enrichment indirectly increased the richness of AMF via increased exotic plant cover in P-limited eucalypt woodlands (Albornoz et al., 2023). These findings suggest that soil N enrichment (as a form of ecosystem degradation) and plant invasions could be synergistically linked to the promotion of weedy AMF. We expand on Johnson et al. (2013) to propose that an interaction between soil nutrient availability and changes in plant provenance (i.e. native vs. exotic) could determine the trajectory of AMF associated with nutrient enrichment.

The hypothesised responses of AMF to nutrient enrichment proposed by Johnson et al. (2013) relate to C allocation and AMF abundance. Plant C allocation can mediate competitive interactions among AMF species, with repercussions for their diversity (Knegt et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2015). Hence, consistent with Albornoz et al. (2023), we propose that this hypothesised dependence on N versus P limitation could also apply to AMF species richness. Other nutrients such as potassium (K) could also influence AMF, as they can increase K uptake, potentially for osmotic adjustments as a counter-ion for P uptake (Garcia & Zimmermann, 2014). However, the effects of K or other micronutrients on AMF communities remain unresolved.

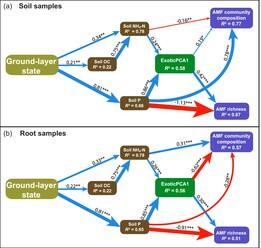

Here, we evaluate the effects of different types of nutrient enrichment and associated plant invasions on AMF in forb-rich York gum (Eucalyptus loxophleba subsp. loxophleba)—Jam (Acacia acuminata) woodlands, an extensive but threatened ecological community of the south-western Australian wheatbelt that is in widespread need of ecological restoration. Soil P is naturally extremely limited, and N is limited, in these woodlands (Prober & Wiehl, 2012). We used a state-and-transition approach to compare York gum woodland ground layers in a close-to-reference (near-natural) state with three modified states: (1) weakly invaded by exotic annuals and weakly enriched in N and P (hereafter ‘weakly invaded/enriched’), (2) moderately invaded by exotic annuals and enriched in N (hereafter ‘moderately invaded/N-enriched’), and (3) highly invaded by exotic annuals and enriched in P, N and other nutrients (hereafter ‘highly invaded/NP-enriched’). We hypothesised:

H1.AMF richness is highest where N enrichment promotes exotic plant invaders and exacerbates P limitation. In contrast, AMF richness is lowest where N- and P enrichment reduces host reliance on AMF for nutrient acquisition.

H2.AMF richness and colonisation are higher in exotic than in native plant species due to exotics' reliance on AMF for nutrient acquisition.

H3.Changes in AMF communities reflect changes in soil nutrients and shift from native-dominated to exotic-dominated vegetation.

中文翻译:

磷限制桉树林地中丛枝菌根群落对养分富集和植物入侵的反应

1 简介

为了帮助扭转全球生物多样性和生态系统的迅速衰退,《生物多样性公约》通过了《昆明-蒙特利尔全球生物多样性框架》,旨在“确保到2030年至少30%的陆地、内陆水域和海洋退化地区”沿海生态系统得到有效恢复”(《生物多样性公约》, 2022 )。为了优化恢复结果,我们必须首先了解阻碍恢复的机制。外来植物和营养富集通常是恢复的重要限制(Corbin & D'Antonio, 2012 ),并且这些通常是相互关联的(Standish 等, 2006 )。因此,解决外来植物与非生物和生物土壤遗产之间的植物-土壤反馈的恢复工作可能会增加成功的机会(Eviner&Hawkes, 2008 )。

生物土壤遗产可能包括有益土壤微生物(例如丛枝菌根真菌(AMF))丰度和组成的变化。丛枝菌根真菌是植物互利共生体,可以增加植物磷(P)和水的吸收(Smith&Read, 2010 ),提供病原体防御(Veresoglou&Rillig, 2012 ),改善土壤理化性质(Willis等, 2013 )并有助于养分循环(Powell & Rillig, 2018 )。它们是生态系统健康的关键组成部分,重新引入原生 AMF 已被证明可以促进退化后的植被恢复(Neuenkamp 等人, 2019 )。

养分富集是原生生态系统退化的一种形式,即土壤的养分与其固有水平相比变得富集。例如,这种情况可能通过施肥、全球氮 (N) 沉积或受干扰植被释放养分而发生,通常导致外来植物入侵和本土多样性丧失(Prober & Wiehl, 2012 )。这些变化可能与关键 AMF 的丧失或“杂草”AMF 的到来有关,这两者反过来可能会阻碍生态系统的恢复(Albornoz 等, 2023 )。我们将“杂草 AMF”定义为那些到达并持续存在于退化生态系统中或在退化生态系统中得到推广的生物,无论它们是本地的还是外来的。

有人提出,基于李比希最小值定律(von Liebig 1840),土壤和植物 N:P 化学计量可以确定养分富集对 AMF 的影响(Johnson 等, 2013 )。如果原生生态系统天然受到磷限制或磷和氮共同限制,则氮富集预计会加剧磷限制,可能会增加植物对其共生体的依赖并促进 AMF。或者,在磷容易获得而氮受到限制的生态系统中,氮富集应该减轻植物养分的共同限制,潜在地减少植物将碳(C)分配给AMF的需要(Johnson等, 2013 )。因此,Leff 等人在对 25 个草原进行的全球研究中。 ( 2015 )表明施氮和磷肥降低了AMF的相对丰度。在高水平的氮和磷可用性下,植物多样性也会降低(Seabloom et al., 2021 ),由于寄主多样性低,可能会进一步限制 AMF。

在磷极度贫乏的生态系统中,由于在这些贫瘠土壤上进化的其他磷获取策略的竞争优势,非 AMF 植物物种的比例往往较高(Lambers 等, 2011 ),可能会降低宿主多样性和丰富的AMF。因此,富氮促进的植物入侵可以增加宿主的可用性,进一步促进 AMF。例如,在最近的一项研究中,我们表明,氮富集通过增加磷限制桉树林地中的外来植物覆盖来间接增加 AMF 的丰富度(Albornoz 等人, 2023 )。这些发现表明,土壤氮富集(作为生态系统退化的一种形式)和植物入侵可能与杂草 AMF 的促进存在协同联系。我们对约翰逊等人进行了扩展。 ( 2013 ) 提出土壤养分有效性和植物来源变化(即本地与外来)之间的相互作用可以决定与养分富集相关的 AMF 轨迹。

Johnson 等人提出的 AMF 对营养富集的假设反应。 ( 2013 )与C分配和AMF丰度有关。植物碳分配可以介导 AMF 物种之间的竞争性相互作用,对其多样性产生影响(Knegt 等, 2016 ;Liu 等, 2015 )。因此,与 Albornoz 等人的观点一致。 ( 2023 ),我们提出这种对氮与磷限制的假设依赖性也适用于 AMF 物种丰富度。其他营养物质如钾 (K) 也可能影响 AMF,因为它们可以增加 K 的吸收,可能作为 P 吸收的反离子进行渗透压调节(Garcia & Zimmermann, 2014 )。然而,钾或其他微量营养素对 AMF 群落的影响仍未解决。

在这里,我们评估了不同类型的营养富集和相关植物入侵对富含福尔博的约克胶( Eucalyptus loxophleba subsp. loxophleba )-果酱( Acacia acuminata )林地中AMF的影响,这是西南地区一个广泛但受到威胁的生态群落澳大利亚小麦带普遍需要生态恢复。在这些林地中,土壤 P 自然极其有限,N 也有限(Prober & Wiehl, 2012 )。我们使用状态和转变方法将接近参考(接近自然)状态的约克胶林地地层与三种修改状态进行比较:(1)受外来一年生植物微弱入侵且 N 和 P 微弱富集( (下文中称为“弱入侵/富集”),(2) 受到外来一年生植物中度入侵,并富含 N(下文中称为“中度入侵/富氮”),以及 (3) 受到外来一年生植物高度入侵,并富含 P、N 和其他元素营养物质(以下简称“高度侵入/富含 NP”)。我们假设:

H1。当氮富集促进外来植物入侵并加剧磷限制时,AMF 丰富度最高。相比之下,当氮和磷富集减少宿主对 AMF 获取养分的依赖时,AMF 丰富度最低。

H2。由于外来植物依赖 AMF 获取养分,因此外来植物的 AMF 丰富度和定植率高于本地植物。

H3。 AMF 群落的变化反映了土壤养分的变化以及从本地植被为主向外来植被为主的转变。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号