Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-07-01 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14361 Damaris Zurell 1 , Niklaus E. Zimmermann 2 , Philipp Brun 2

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Why do species occur at specific locations but not elsewhere? This is a central question in ecology and biogeography and has become ever more relevant as climate change is causing major species redistributions across the globe (Lenoir et al., 2020; Pecl et al., 2017). With the increasing availability of georeferenced species observations and gridded environmental data (Wüest et al., 2020), correlative species distribution models (SDMs) have become a powerful tool for understanding and predicting species distributions (Elith & Leathwick, 2009; Guisan et al., 2017; Guisan & Zimmermann, 2000). SDMs relate observed species occurrences to prevailing environmental conditions, using appropriate statistical and machine learning techniques. The fitted species–environment relationship can then be interpreted as the hypothesised species environmental preferences or can be used to predict the occurrence probability of a species for a given set of environmental conditions. Potential applications of SDMs are manifold, ranging from testing hypotheses about species' ecology and range determinants (Chauvier, Thuiller, et al., 2021; Normand et al., 2009; Zimmermann et al., 2009), biogeographic history (Normand et al., 2011), to informing protected area design (Albert et al., 2017; Chauvier et al., 2024), and predicting potential future distributions and threat status under scenarios of climate change (Brun et al., 2020; Zurell et al., 2018, 2023).

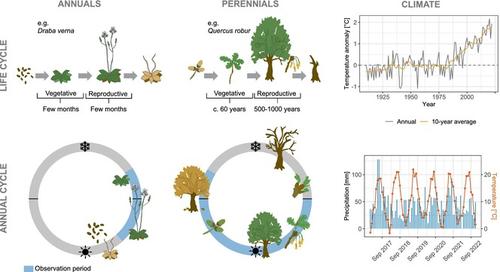

SDMs are tightly linked to the niche concept. The ecological niche comprises all environmental conditions that allow positive population growth and under which the species can persist indefinitely (usually characterised by successful reproduction and survival) (Hutchinson, 1957). As the interest in SDM applications grew immensely over the last three decades, much attention has been given to method development (Brun et al., 2020; Chauvier, Zimmermann, et al., 2021), method testing (Elith et al., 2006; Valavi et al., 2022) and definition and implementation of standards (Araújo et al., 2019; Zurell et al., 2020). Also, the role of spatial scale and scale dependency has been widely acknowledged (Guisan & Thuiller, 2005) and tested (Adde et al., 2023; König et al., 2021). It is generally accepted that (macro-)climate drives large-scale species distributions while factors related to habitat availability and soil resources but also topography and microclimate drive small-scale variations in species occurrence (Descombes et al., 2020; Guisan & Thuiller, 2005; Lembrechts et al., 2019; McGill, 2010). Thus, the components of the niche that can be identified by SDMs depend on the spatial resolution and extent of the data and analyses. By contrast, the role of time has been less often discussed in the context of SDMs (Ponti & Sannolo, 2023). Here, we argue that temporal components related to species' phenological and demographic stages can be highly relevant for fitting plant SDMs. Phenological events like budburst, flowering and seed set are related to specific environmental conditions that will determine successful reproduction and survival at any given location. Changes in plant phenology have been reported in response to climate change with potential effects cascading through entire food webs and ecosystems (Scheffers et al., 2016; Vitasse et al., 2022). Additionally, phenology may mediate the detection probability of species across space as some phenological stages might be more conspicuous than others. Demographic stages (or life stages) describe key phases in the life cycle of a species that may differ substantially in their environmental tolerance, for example in response to environmental conditions, such as frost, and limited availability of resources, such as water. For example, the juveniles of many tree species have been found to have narrower climatic niches than adults (Dobrowski et al., 2015; Ellenberg, 2009). Ignoring the relevance of phenological and demographic stages for detecting the species and for identifying range-limiting factors could lead to biased niche estimates in SDMs and to fallacious predictions into the future.

In this review, we aim to draw attention to temporal components of the niche and how they are typically considered (or not) in SDMs. We illuminate this topic with a systematic literature review and discuss conceptual and methodological perspectives. First, we identify relevant temporal components of species–environment relationships and conduct a Web of Science literature search to assess the current representation of temporal components in plant SDMs. Second, we discuss these temporal components in more detail and reflect on the niche concept in light of environmental seasonality and species' ontogeny and potential consequences for SDM calibration and inference. Last, we provide an overview of methods that can be used for considering phenology and demographic stages in SDMs and discuss opportunities and challenges for future research. Our review emphasises that explicitly considering temporal components of the niche in SDMs allows an improved mechanistic understanding of niche and range determinants and deeper insights into species spatial and temporal response to historic as well as contemporary climate change.

中文翻译:

随时间变化的生态位:考虑植物分布模型中的物候和人口阶段

1 简介

为什么物种出现在特定地点而不是其他地方?这是生态学和生物地理学的一个核心问题,随着气候变化导致全球主要物种重新分布,这一问题变得越来越重要(Lenoir 等, 2020 ;Pecl 等, 2017 )。随着地理参考物种观测和网格化环境数据的不断增加(Wüest 等, 2020 ),相关物种分布模型(SDM)已成为理解和预测物种分布的强大工具(Elith & Leathwick, 2009 ;Guisan 等,2020)。 , 2017 ;吉桑和齐默尔曼, 2000 )。 SDM 使用适当的统计和机器学习技术,将观察到的物种发生与普遍的环境条件联系起来。然后,拟合的物种-环境关系可以解释为假设的物种环境偏好,或者可以用于预测给定环境条件下物种的出现概率。 SDM 的潜在应用是多方面的,从测试有关物种生态和范围决定因素的假设(Chauvier, Thuiller, et al., 2021 ;Normand et al., 2009 ;Zimmermann et al., 2009 ),生物地理学历史(Normand et al., 2009) ., 2011 ),为保护区设计提供信息(Albert 等, 2017 ;Chauvier 等, 2024 ),并预测气候变化情景下潜在的未来分布和威胁状态(Brun 等, 2020 ;Zurell 等) ., 2018 , 2023 ).

SDM 与利基概念紧密相关。生态位包括允许种群积极增长并且物种可以无限期持续的所有环境条件(通常以成功繁殖和生存为特征)(Hutchinson, 1957 )。随着过去三十年对 SDM 应用的兴趣极大增长,方法开发(Brun 等人, 2020 ;Chauvier、Zimmermann 等人, 2021 )、方法测试(Elith 等人, 2006 )受到了极大的关注。 ;Valavi 等人, 2022 年)以及标准的定义和实施(Araújo 等人, 2019 年;Zurell 等人, 2020 年)。此外,空间尺度和尺度依赖性的作用已得到广泛认可(Guisan & Thuiller, 2005 )并经过测试(Adde 等人, 2023 ;König 等人, 2021 )。人们普遍认为,(宏观)气候驱动大规模物种分布,而与栖息地可用性和土壤资源相关的因素以及地形和小气候也驱动物种出现的小规模变化(Descombes 等, 2020 ;Guisan 和 Thuiller, 2005 ;伦布雷希特等人, 2019 ;麦吉尔, 2010 )。因此,SDM 可以识别的生态位组成部分取决于数据和分析的空间分辨率和范围。相比之下,在 SDM 的背景下,时间的作用很少被讨论(Ponti & Sannolo, 2023 )。在这里,我们认为与物种物候和人口统计阶段相关的时间成分可能与拟合植物 SDM 高度相关。 发芽、开花和结籽等物候事件与特定的环境条件有关,这些条件将决定在任何特定地点的成功繁殖和生存。据报道,植物物候的变化是为了应对气候变化,并可能对整个食物网和生态系统产生级联影响(Scheffers 等, 2016 ;Vitasse 等, 2022 )。此外,物候学可能会调节跨空间物种的检测概率,因为某些物候阶段可能比其他阶段更明显。人口阶段(或生命阶段)描述了物种生命周期中的关键阶段,这些阶段的环境耐受性可能存在很大差异,例如对霜冻等环境条件和水等有限可用资源的响应。例如,许多树种的幼树被发现比成树具有更窄的气候生态位(Dobrowski et al., 2015 ;Ellenberg, 2009 )。忽略物候和人口统计阶段在检测物种和识别范围限制因素方面的相关性可能会导致 SDM 中的生态位估计存在偏差,并对未来做出错误的预测。

在这篇综述中,我们的目的是引起人们对生态位的时间组成部分的关注,以及它们在 SDM 中通常如何被考虑(或不被考虑)。我们通过系统的文献综述来阐明这个主题,并讨论概念和方法论的观点。首先,我们确定了物种与环境关系的相关时间成分,并进行了 Web of Science 文献检索,以评估植物 SDM 中时间成分的当前表征。其次,我们更详细地讨论这些时间成分,并根据环境季节性和物种个体发育以及 SDM 校准和推理的潜在后果反思生态位概念。最后,我们概述了可用于考虑 SDM 中物候和人口阶段的方法,并讨论了未来研究的机遇和挑战。我们的综述强调,明确考虑 SDM 中生态位的时间组成部分可以改善对生态位和范围决定因素的机械理解,并更深入地了解物种对历史和当代气候变化的空间和时间响应。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号