Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-06-17 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14350 Laurie Dupont‐Leduc 1 , Hugues Power 2 , Mathieu Fortin 3 , Robert Schneider 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

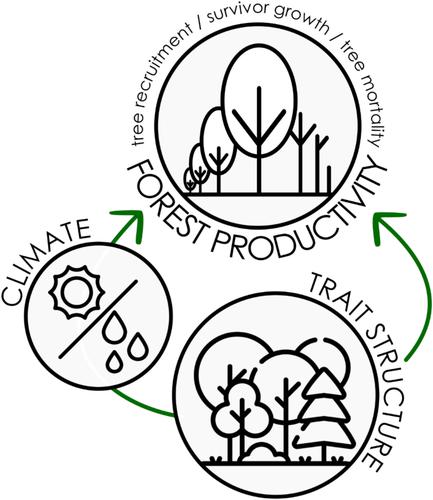

Diverse forests can be more productive than species-poor ones (Forrester, 2017; Liang et al., 2007, 2016; Paquette & Messier, 2011; Pretzsch, del Río, et al., 2015; Pretzsch, Forrester, et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2021). The positive mixing effects may reflect complementarity interactions, such as niche differentiation (i.e. where two or more species occupy distinct spatial niches enhancing collective performance) and facilitation (i.e. where one species positively influences another, directly or indirectly, by increasing its growth or survival) (Callaway, 1995; Loreau, 2000; Loreau & Hector, 2001). Competition between two species can be reduced if they differ in their use of a resource, for example one being adapted to the use of light found in the understorey, while another is specialized in the use of light higher up in the canopy (Man & Lieffers, 1999; Pretzsch, del Río, et al., 2015; Pretzsch, Forrester, et al., 2015) or one species can increase the amount of nitrogen available for another by increasing litter decomposition rates (del Río & Sterba, 2009; Man & Lieffers, 1999). The differential sensitivity of species to specific disturbance agents (e.g. diseases, pathogens, defoliation and climate) could also contribute to the positive mixing effect (Jucker et al., 2016; Pretzsch, 2005; Sousa-Silva et al., 2018). By studying the trait structure of communities, more attention is paid to the role of each organism in the ecosystem and to the attributes needed to maintain ecosystem functioning (Reiss et al., 2009). A trait can be defined as ‘a measurable characteristic (morphological, phenological, physiological, behavioural, or cultural) of an individual organism that is measured at either the individual or other relevant level of organizational’ (Dawson et al., 2021). One of the fundamental advantages of their use is that they can provide generalizations across species and taxa, revealing the different ecological strategies involved in species assemblages (Dawson et al., 2021; Kraft et al., 2015; Shipley et al., 2016), and as such, inferences are more generalizable beyond the immediate study system. Thus, this approach enables the study of the mechanisms underlying the diversity–ecosystem function relationships and recognizes that some mixtures can be more complementary than others (Lavorel et al., 2008). Forest productivity can be studied as a net value (i.e. net forest productivity, NFP), defined as the biomass remaining after subtracting the losses through tree mortality (i.e. trees that have died between two measurements) from the gain of survivor growth (i.e. growth of trees that survived between two consecutive plot measurements) and tree recruitment (i.e. trees that reach 9.1 cm DBH between two measurements) (Pretzsch, 2009). However, relatively few studies have examined the effect of the trait structure of tree communities on forest productivity in relation to demographic processes, namely survivor growth, recruitment and mortality, which all contribute to forest population dynamics (Condés & del Río, 2015; Liang et al., 2007; Looney et al., 2021).

Along with the trait structure, climate also represents a major determinant of forest productivity (Ammer, 2019). As reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global temperatures in the northern midlatitudes are projected to increase by 1.5–2°C and temperature extremes by 3–4°C, depending on the scenario (Allen et al., 2019; Ammer, 2019; Kirilenko & Sedjo, 2007), increases that will undoubtedly affect many forest ecosystems. As disturbances become more frequent or more intense (Dale et al., 2001), interactions among species will be altered. These changes will affect population dynamics and, therefore, ecosystem functions and services, of which productivity is a key feature (Ammer, 2019; Silva Pedro et al., 2016).

Currently, promoting tree diversity is seen as a promising avenue to adapt to climate change in current forestry practices (Ammer, 2019; Kolström et al., 2011; Looney et al., 2021; Pretzsch, del Río, et al., 2015; Pretzsch, Forrester, et al., 2015). A combination of different approaches can be used to help an ecosystem to functionally recover after changes (Thompson et al., 2009), either through resistance (i.e. the absence of change), resilience (i.e. the return to the initial state after a disturbance) or response (i.e. strengthening the capacity of forests respond to change) (Hörl et al., 2020; Malmsheimer et al., 2008; Millar et al., 2007). However, recent studies have shown contrasting patterns concerning the effect of tree diversity on the ability of some stands to maintain their productivity when subjected to climate change (CC) (Jucker et al., 2016; Paquette et al., 2017). Mitigating the effects of CC on forests requires identifying and understanding the circumstances under which tree species diversity has the utmost potential to positively influence forest productivity and its components, information that has important implications for forest management and forest conservation.

Our study had two goals. The first one was to understand how the structure of traits within tree communities influences the different components of forest productivity (survivor growth, recruitment of new trees and mortality) over a wide latitudinal and longitudinal gradient in northeastern North America. We proposed to address this question by using trait values from the literature to analyse the trait structure of tree communities within a large network of periodically measured permanent sample plots (PSP). It can be assumed that the trait structure of communities affects each component of forest productivity differently. Indeed, it is expected that (i) leaf traits are associated with survivor growth because they are important for overall plant functioning, whereas (ii) traits related to resource acquisition have the largest impact on tree recruitment, and (iii) those related to competition and survival strategies play a more notable role in tree mortality. Our second goal was related to the effects of CC on forest productivity and motivated by this question: Does the trait structure of a community influence its ability to respond to climatic variations? We hypothesized that (iv) forests with the highest functional diversity have better adaptive capacity to an altered climate than those with the lowest diversity. To do this, we used annual temperature and precipitation to investigate how tree communities responded to a range of climatic conditions. The relationships between trait structure, productivity and climate may provide insights to evaluate under which circumstances tree species diversity can enhance forest productivity under CC.

中文翻译:

气候与树木群落性状结构相互作用,影响森林生产力

1 简介

多样化的森林比物种贫乏的森林生产力更高(Forrester,2017;Liang 等,2007、2016;Paquette & Messier,2011;Pretzsch、del Río 等,2015;Pretzsch、Forrester 等, 2015;张等人,2012;郑等人,2021)。积极的混合效应可能反映了互补性相互作用,例如生态位分化(即两个或多个物种占据不同的空间生态位,从而增强集体表现)和促进作用(即一个物种通过增加其生长或生存,直接或间接地积极影响另一个物种) (卡拉威,1995 年;洛罗,2000 年;洛罗和赫克托,2001 年)。如果两个物种对资源的使用不同,则可以减少它们之间的竞争,例如,一个物种适应使用下层植物中的光,而另一种则专门使用树冠较高处的光(Man & Lieffers) ,1999;Pretzsch,del Río,et al.,2015;Pretzsch,Forrester,et al.,2015)或一个物种可以通过提高凋落物分解率来增加另一种物种可用的氮量(del Río&Sterba,2009;Man)和利弗斯,1999)。物种对特定干扰因素(例如疾病、病原体、落叶和气候)的不同敏感性也可能有助于产生积极的混合效应(Jucker et al., 2016;Pretzsch, 2005;Sousa-Silva et al., 2018)。通过研究群落的性状结构,人们更加关注生态系统中每种生物的作用以及维持生态系统功能所需的属性(Reiss等,2009)。 特征可以定义为“在个体或其他相关组织层面上测量的个体有机体的可测量特征(形态、物候、生理、行为或文化)”(Dawson 等人,2021)。使用它们的基本优势之一是它们可以提供跨物种和类群的概括,揭示物种组合中涉及的不同生态策略(Dawson 等人,2021;Kraft 等人,2015;Shipley 等人,2016) ,因此,推论在直接研究系统之外更具普遍性。因此,这种方法能够研究多样性与生态系统功能关系背后的机制,并认识到某些混合物可能比其他混合物更具互补性(Lavorel 等,2008)。森林生产力可以作为净值(即净森林生产力,NFP)来研究,定义为从幸存者生长的增益(即树木的生长)中减去树木死亡率造成的损失(即两次测量之间死亡的树木)后剩余的生物量。两次连续地块测量之间存活的树木)和树木补充(即两次测量之间胸径达到 9.1 厘米的树木)(Pretzsch,2009)。然而,相对较少的研究考察了树木群落特征结构对与人口过程相关的森林生产力的影响,即幸存者的生长、补充和死亡率,这些都有助于森林种群动态(Condés&del Río,2015;Liang等人)卢尼等人,2007 年;卢尼等人,2021 年)。

除了性状结构之外,气候也是森林生产力的主要决定因素(Ammer,2019)。据政府间气候变化专门委员会 (IPCC) 报告,根据具体情况,北部中纬度地区的全球气温预计将上升 1.5–2°C,极端气温将上升 3–4°C(Allen 等,2019) ;Ammer,2019;Kirilenko & Sedjo,2007),这无疑会影响许多森林生态系统。随着干扰变得更加频繁或更加强烈(Dale 等,2001),物种之间的相互作用将会改变。这些变化将影响人口动态,从而影响生态系统功能和服务,其中生产力是一个关键特征(Ammer,2019;Silva Pedro 等,2016)。

目前,促进树木多样性被视为当前林业实践中适应气候变化的一个有前途的途径(Ammer,2019;Kolström 等,2011;Looney 等,2021;Pretzsch,del Río 等,2015; Pretzsch、Forrester 等,2015)。可以使用不同方法的组合来帮助生态系统在变化后功能恢复(Thompson et al., 2009),可以通过抵抗(即没有变化)、恢复力(即在干扰后恢复到初始状态)或响应(即加强森林应对变化的能力)(Hörl 等人,2020 年;Malmsheimer 等人,2008 年;Millar 等人,2007 年)。然而,最近的研究表明,树木多样性对某些林分在遭受气候变化(CC)时保持生产力的能力的影响存在着对比模式(Jucker等人,2016年;Paquette等人,2017年)。减轻CC对森林的影响需要确定和了解树种多样性最有可能对森林生产力及其组成部分产生积极影响的情况,这些信息对森林管理和森林保护具有重要影响。

我们的研究有两个目标。第一个是了解北美东北部广泛的纬度和经度梯度上树木群落内的性状结构如何影响森林生产力的不同组成部分(幸存者生长、新树补充和死亡率)。我们建议通过使用文献中的性状值来分析定期测量的永久样地(PSP)的大型网络中树木群落的性状结构来解决这个问题。可以假设群落的性状结构对森林生产力的各个组成部分的影响不同。事实上,预计 (i) 叶子性状与存活者生长相关,因为它们对植物的整体功能很重要,而 (ii) 与资源获取相关的性状对树木补充影响最大,以及 (iii) 与竞争相关的性状生存策略在树木死亡率中发挥着更显着的作用。我们的第二个目标与 CC 对森林生产力的影响有关,并受到以下问题的启发:群落的特征结构是否影响其应对气候变化的能力?我们假设(iv)功能多样性最高的森林比多样性最低的森林对气候变化有更好的适应能力。为此,我们利用年气温和降水量来调查树木群落对一系列气候条件的反应。性状结构、生产力和气候之间的关系可以为评估在何种情况下树种多样性可以提高 CC 下的森林生产力提供见解。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号