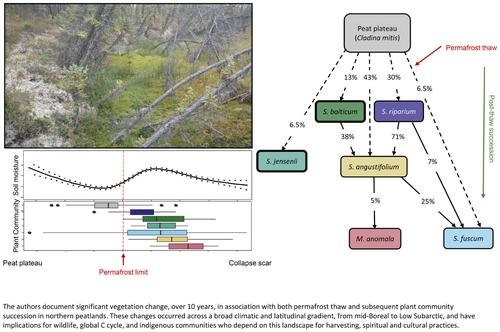

Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2024-06-14 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14339 Ruth C. Errington 1, 2 , S. Ellen Macdonald 2 , Jagtar S. Bhatti 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Climate change is a global issue, with observed and predicted warming being markedly pronounced in northern regions (Gulev et al., 2021; IPCC, 2023). There is, therefore, a critical need to understand how warming climate conditions are directly and indirectly affecting northern plant communities. The Mackenzie Valley region of the Northwest Territories (NWT) has been identified as one of the most sensitive areas to climate warming in Canada (Kettles & Tarnocai, 1999; Tarnocai, 2006) due to the prevalence of ice-rich permafrost, coupled with the magnitude of both realized (Zhang et al., 2000) and projected (Plummer et al., 2006; Price et al., 2011) climate change. In the boreal and subarctic forests of the Mackenzie Valley, much of this ice-rich permafrost occurs as peat plateau landforms, which are raised approximately 1 m above the surrounding, unfrozen peat landscape; these have relatively flat surfaces and can extend for several square kilometres (Vitt et al., 1994). Due to the insulating properties of dry surface peat layers, discontinuous permafrost is preferentially found in peatlands, with the most southerly limit of permafrost in Canada located almost exclusively within ombrotrophic peatland environments (Beilman et al., 2001; Halsey et al., 1995; Vitt et al., 1994).

Within peat plateaux, aggradation and degradation of permafrost is known to be a cyclic phenomenon (Zoltai, 1993). A slight increase in soil temperature, often resulting from disturbance of insulating vegetation or peat layers due to fire (Gibson et al., 2018; Zoltai, 1993), can result in permafrost thaw. This is particularly the case in the more southerly sporadic discontinuous permafrost zone, where ground ice temperatures are close to zero degrees (Smith et al., 2010). Recent climatic warming has been associated with higher rates of permafrost degradation than aggradation, for example in the southern Mackenzie Valley losses of 10%–51% of permafrost area have been detected (Beilman & Robinson, 2003; Quinton et al., 2011). Many of the effects of permafrost thaw propagate through the landscape, via changes to the regional hydrology (Quinton et al., 2009). For northern communities that depend on these forested landscapes for spiritual and cultural practices, as well as for subsistence harvesting (Guyot et al., 2006; Parlee et al., 2005), it is particularly important to understand how northern forest and peatland ecosystems are changing and how they may continue to change under warming climate conditions.

As permafrost thaws within a peat plateau, the loss of ice volume causes the ground surface to subside approximately 1 m, forming collapse scar features, in which the water table is commonly within 10 cm of the ground surface. This results in a transition from lichen-dominated ground vegetation to very wet, moss and sedge-dominated collapse scar features (Camill, 1999a, 1999b) affecting plant community composition and diversity (Beilman, 2001). This is followed by a classic autogenic successional sequence driven by Sphagnum species and regulated by species-driven changes in water chemistry and water table depth. As peat accumulation raises the ground surface above the minerotrophic ground water table, the surface water conditions increasingly reflect the more acidic, ombrotrophic conditions associated with precipitation-derived surface water (Rydin & Jeglum, 2006; Vitt, 1994). This acidification is further encouraged by Sphagnum species (Clymo, 1963; Rydin et al., 2006; Spearing, 1972) and autogenic successional sequences are observed as peat accumulation increases the height above water table (HAWT), lessening the influence of minerotrophic groundwater (e.g. Arlen-Pouliot & Bhiry, 2005; Errington, 2006; Horton et al., 1979). With post-collapse succession causing the growing moss surface to be raised successively higher above the water table (Robinson & Moore, 2000; Zoltai, 1993) dry surface peat will, once again, allow for the process of permafrost aggradation to begin if climatic conditions are favourable (Zoltai, 1993). However, relict permafrost, occurring in areas where the climate is no longer conducive to permafrost formation, will disappear from the landscape (Beilman et al., 2001; Halsey et al., 1995). Estimates from peat cores in Manitoba, Canada indicate that succession from aquatic to hummock Sphagnum species can occur in as little as 50–80 years following permafrost collapse (Camill, 1999b). However, Zoltai (1993) determined that it took a minimum of 600 years for permafrost to re-establish in peat plateaux of northeastern Alberta, Canada.

Because vegetation succession post-collapse is very closely associated with peat accumulation above the water table, the timing of this successional sequence has direct relevance to the global C cycle and climate warming feedbacks. Permafrost thaw results in an initial loss of carbon (Jones et al., 2017) and collapse scars are associated with greater methane (CH4) emissions (Johnston et al., 2014; Liblik et al., 1997). However, collapse scars also have increased rates of carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration (Startsev et al., 2016), and greater apparent rates of peat carbon (C) accumulation (Robinson & Moore, 2000) such that they become net C sinks approximately one-decade post-collapse (Jones et al., 2017). Both CH4 emissions and CO2 sequestration rates vary with time since collapse (Estop-Aragonés et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2014), with CH4 emissions largely controlled by water table depth, soil temperature and vegetation composition (Olefeldt et al., 2013). Peatland bryophytes are highly sensitive to changes in local hydrologic conditions, with the niche spaces of individual Sphagnum species tightly constrained by water table depth (Gignac et al., 1991; Nicholson & Gignac, 1995). Thus, peatland bryophytes can be used to generate localized predictions of CH4 emissions from boreal and subarctic peatlands (Bubier, Moore, & Juggins, 1995).

Our first objective was to quantify the lateral thaw rate of collapse scar margins, and to determine if this rate of thaw was greater in warmer, more southerly regions. We hypothesized that lateral rates of collapse scar expansion would range from 0 to 50 cm year−1 and that this would be higher in regions with warmer climate conditions as permafrost would be at a warmer temperature and more susceptible to thaw (Camill, 2005; Camill & Clark, 1998). Our second objective was to describe the sequence and rate of successional change of vegetation communities following thaw, and subsequent collapse of the peat plateau permafrost, and how this related to local environmental conditions. We hypothesized that permafrost collapse would be associated with a dramatic loss of almost all species from the system with initial colonization by a floating mat of Sphagnum mosses and rhizomatous sedges. This would be followed by an autogenic successional sequence similar to that observed in non-permafrost peatlands, characterized by a series of Sphagnum species replacing one another as the peat surface grows above the water table. We further predict that species richness and diversity will increase, with greater representation of forb and shrub species, as the peat surface grows above the water table, increasing the oxygenated rooting zone, and hummock formation increases the topographic complexity.

中文翻译:

加拿大西北部泥炭地永久冻土融化速度及相关植物群落动态

1 简介

气候变化是一个全球性问题,观测到和预测的北部地区变暖现象明显(Gulev 等,2021;IPCC,2023)。因此,迫切需要了解气候变暖如何直接和间接影响北方植物群落。由于普遍存在富含冰的永久冻土,加上西北地区(NWT)的麦肯齐谷地区被认为是加拿大对气候变暖最敏感的地区之一(Kettles & Tarnocai,1999;Tarnocai,2006)。实际(Zhang 等,2000)和预计(Plummer 等,2006;Price 等,2011)气候变化的幅度。在麦肯齐山谷的北方和亚北极森林中,大部分富含冰的永久冻土都是泥炭高原地貌,比周围未冻泥炭地貌高出约 1 m;它们具有相对平坦的表面,可以延伸几平方公里(Vitt et al., 1994)。由于干燥表面泥炭层的绝缘特性,不连续的永久冻土优先在泥炭地中发现,加拿大永久冻土的最南端几乎完全位于营养泥炭地环境中(Beilman等人,2001年;Halsey等人,1995年;维特等人,1994)。

在泥炭高原内,永久冻土的加剧和退化是一种循环现象(Zoltai,1993)。土壤温度的轻微升高通常是由于火灾对绝缘植被或泥炭层的干扰造成的(Gibson 等人,2018 年;Zoltai,1993 年),可能会导致永久冻土融化。在更南边的零星不连续永久冻土区尤其如此,那里的地面冰温接近零度(Smith 等,2010)。最近的气候变暖与永久冻土退化率高于退化率有关,例如,在麦肯齐山谷南部,已发现永久冻土面积损失了 10%–51%(Beilman & Robinson,2003 年;Quinton 等人,2011 年)。永久冻土融化的许多影响通过区域水文的变化而在整个景观中传播(Quinton 等,2009)。对于依赖这些森林景观进行精神和文化实践以及维持生计的采伐的北方社区来说(Guyot 等人,2006 年;Parlee 等人,2005 年),了解北方森林和泥炭地生态系统的状况尤为重要。变化以及在气候变暖的条件下它们将如何继续变化。

当泥炭高原内的永久冻土融化时,冰量的损失导致地表下沉约1 m,形成塌陷疤痕特征,其中地下水位通常在距地表10 cm以内。这导致从地衣为主的地面植被转变为非常潮湿、苔藓和莎草为主的塌陷疤痕特征(Camill,1999a,1999b),影响植物群落组成和多样性(Beilman,2001)。接下来是由泥炭藓物种驱动的经典自生演替序列,并受物种驱动的水化学和地下水位深度变化的调节。随着泥炭的积累使地表升高到矿营养地下水位以上,地表水状况日益反映出与降水产生的地表水相关的酸性更强的反营养状况(Rydin & Jeglum,2006;Vitt,1994)。泥炭藓物种进一步促进了这种酸化(Clymo,1963;Rydin 等,2006;Spearing,1972),并且随着泥炭积累增加了地下水位以上高度(HAWT),观察到自生演替序列,从而减轻了矿营养地下水的影响(例如,Arlen-Pouliot 和 Bhiry,2005;Errington 等人,1979 年。随着塌陷后的演替,导致生长的苔藓表面逐渐升高到地下水位以上(Robinson & Moore,2000;Zoltai,1993),如果气候条件允许,干燥的地表泥炭将再次允许永久冻土加积的过程开始。是有利的(Zoltai,1993)。然而,在气候不再有利于永久冻土形成的地区出现的残余永久冻土将从景观中消失(Beilman等人,2001年;Halsey等人,1995年)。 对加拿大马尼托巴省泥炭岩芯的估计表明,在永久冻土崩塌后短短 50-80 年内,水生泥炭藓物种就会演变成丘状泥炭藓物种(Camill,1999b)。然而,Zoltai(1993)确定,加拿大阿尔伯塔省东北部的泥炭高原至少需要 600 年才能重新形成永久冻土。

由于塌陷后的植被演替与地下水位以上的泥炭积累密切相关,因此这种演替顺序的时间与全球碳循环和气候变暖反馈直接相关。永久冻土融化会导致碳的初始损失(Jones 等人,2017 年),塌陷疤痕与更多的甲烷 (CH 4 ) 排放有关(Johnston 等人,2014 年;Liblik 等人,1997 年) )。然而,塌陷疤痕也增加了二氧化碳 (CO 2 ) 封存率 (Startsev et al., 2016),并且泥炭碳 (C) 积累率也更高 (Robinson & Moore, 2000),例如大约在崩溃后十年,它们就会成为净碳汇(Jones et al., 2017)。 CH 4 排放量和 CO 2 封存率均随塌陷后的时间而变化(Estop-Aragonés 等人,2018 年;Johnston 等人,2014 年),其中 CH 4 排放的局部预测(Bubier、Moore 和 Juggins,1995)。

我们的第一个目标是量化塌陷疤痕边缘的横向解冻速率,并确定该解冻速率在更温暖、更靠南的地区是否更大。我们假设塌陷疤痕横向扩展速度范围为 0 至 50 厘米/年 −1 ,并且在气候条件较温暖的地区,该速度会更高,因为永久冻土的温度较高,更容易融化(卡米尔,2005;卡米尔和克拉克,1998)。我们的第二个目标是描述解冻后植被群落连续变化的顺序和速率,以及随后泥炭高原永久冻土的塌陷,以及这与当地环境条件的关系。我们假设,永久冻土崩塌与系统中几乎所有物种的急剧丧失有关,这些物种最初被泥炭藓和根茎莎草的漂浮垫定殖。随后将出现类似于在非永久冻土泥炭地中观察到的自生演替序列,其特征是随着泥炭表面生长到地下水位以上,一系列泥炭藓物种相互替换。我们进一步预测,随着泥炭表面生长到地下水位以上,增加含氧生根区,以及小丘的形成增加了地形的复杂性,物种丰富度和多样性将会增加,杂草和灌木物种的代表性会更大。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号