Mammal Review ( IF 4.3 ) Pub Date : 2022-07-13 , DOI: 10.1111/mam.12302 Peter A. Seeber 1 , Laura S. Epp 1

|

INTRODUCTION

With approximately 6000 recognised species, mammals are important taxa of almost every known ecosystem and, particularly, of all terrestrial biomes (Jones & Safi 2011). Terrestrial mammals typically exert crucial effects on primary producers through nutrient cycling, energy flow, pollination, seed dispersion, and other bottom-up and top-down processes (Lacher et al. 2019). These functions have marked effects on community structures of primary producers, which again affect communities of primary consumers. However, the current rapid decline in abundances as well as extirpation and extinction of numerous mammal species raise conservation concerns, not only with respect to the taxa in question, but also regarding ecosystem functioning (Lacher et al. 2019). Comprehensive assessment of presence, abundance, and ecological functions of terrestrial mammals requires comprehensive monitoring, preferably with data covering long periods of time. The specific mammal community assemblage, that is taxonomic diversity, relative abundance, and genetic diversity, can be an important indicator of ecosystem functioning and ecosystem changes over time (Lundgren et al. 2020). Thus, monitoring present mammal populations and understanding population changes in the past are important components of terrestrial ecosystem assessments (Morellet et al. 2007).

Extant species assemblages and relative abundances are conventionally assessed by direct observation, live trapping, or camera trapping. However, these methods may be problematic due to considerable logistic effort, the need for long temporal and spatial coverage, and labour-intensive data processing. Moreover, taxonomical resolution by visual identification may in some cases be insufficient where closely related (or phenotypically similar) species are concerned. Such problems are amplified in poorly studied ecosystems that are remote from human infrastructure. Terrestrial mammals continuously shed genetic material into their environment through substances such as faeces, mucus, saliva, aerosol, hair, gametes, epithelial cells, and decomposition of tissue. As such, environmental DNA (eDNA; see Box 1) contains a plethora of information which cannot be captured using traditional methods. Currently, the most common application of eDNA is detecting the presence of a particular taxon in a given habitat (Rees et al. 2014, Ruppert et al. 2019); in this regard, eDNA allows accurate taxonomic resolution to the species level, including cryptic intraspecific genetic diversity (Thomsen & Willerslev 2015), which may reveal unknown biodiversity and can even be used for individual identification (Seeber et al. 2017). In some cases, eDNA-based survey methods can outperform traditional survey approaches to determine species presence (Civade et al. 2016, Deiner et al. 2016). At the genomic level, eDNA can deliver a vast amount of information on wildlife populations, which can offer insights in aspects ranging from individual genetics to evolutionary adaption. The function of mammals as pathogen hosts or vectors is of particular interest regarding the spread of diseases between populations and interspecies transmission. Investigating host genomics and eDNA of pathogens can help elucidate disease transmission patterns (Lang & Blanchong 2012, Dayaram et al. 2021), which may be crucial for conclusions and management measures regarding pathogen dispersal in wild mammals and at the interface of wild and domestic animals.

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) | DNA isolated from environmental samples (such as water or sediment), that was shed from the original live organism, either as extracellular molecule or within cellular compartments |

|---|---|

| Ancient DNA (aDNA) | DNA isolated from ancient specimens, including bulk samples |

| Bulk sample | Samples of environmental material which may include live organisms and eDNA |

| Barcoding | Identifying species using a short, defined genomic region, such as a fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 for animals |

| Metabarcoding | Identifying taxa in samples containing DNA from more than one taxon using the sequence of a genomic region that is suitable for this purpose |

| Metagenetics | Any genetic analyses of samples containing DNA from more than one taxon, using one or few genetic markers |

| Metagenomics | Producing comprehensive genomic data (or data of numerous markers across the genome) from samples containing more than one taxon, that is on a community scale |

| Palaeogenomics | Using ancient DNA to produce genomic data |

Regarding the distributions of terrestrial mammals in the past, research must traditionally rely on organismal remains, which are analysed visually. These can be bones (van der Plicht et al. 2015) and other macroremains, such as hair (Iacumin et al. 2005) or coprolites (Chin & Kirkland 1998). Such direct evidence of mammal presence is not always readily preserved, the probability of discovering fossil remains of mammals is low, and the fossil record is never complete. This means, for example that the youngest fossil of a species never represents the true last appearance – a principle known as the Signor–Lipps effect (Signor & Lipps 1982). In addition to direct evidence, palaeoecological studies can also utilise specific proxies for the presence of mammals, in particular dung fungi (Davies 2019, Goethals & Verschuren 2019) and parasites such as oribatid mites (Chepstow-Lusty et al. 2019).

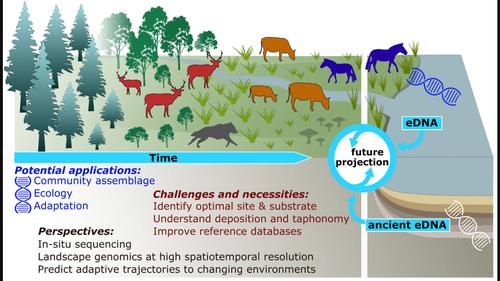

The first study identifying macroorganisms from eDNA targeted ancient DNA (aDNA) of several terrestrial mammals and plants, which was successfully isolated from Siberian permafrost samples (Willerslev et al. 2003). Since this seminal study was published almost two decades ago, considerable progress has been made regarding the use of eDNA of numerous aquatic animals and terrestrial plants, and studies have offered valuable insights into structure and changes in past and current ecosystems (e.g. Deiner et al. 2017, Parducci et al. 2019). By contrast, comparably few studies have focused on terrestrial mammals, despite the vast numbers of potential applications and research questions waiting to be answered, including on biotic interactions in ecosystems, community changes over time, migration patterns, pathogen pressure, and evolutionary adaption to changing environments.

Here, we review studies using DNA from environmental samples and focussed on terrestrial mammals as keystone taxa of many terrestrial environments. We synthesise specific, inherent challenges in adopting eDNA techniques for the study of terrestrial mammals, which explain the relative scarcity of eDNA studies of mammals. We briefly introduce current methodological approaches and elaborate on three aspects of the potential and remaining challenges for eDNA-based studies of terrestrial mammals: 1) obtaining eDNA of terrestrial mammals from different sites and substrates; 2) developing strategies for taxonomic identification of mammalian species assemblages and estimating relative abundances; and 3) deducing information on ecophysiology and behaviour of mammals, as well as on the roles of pathogens, from eDNA. Further, we outline the future of genomic approaches for mammal eDNA to study evolutionary adaptation and aid in species conservation, and we highlight specific potential future applications of (meta)genomic eDNA approaches for mammals.

中文翻译:

陆地哺乳动物的环境 DNA 和宏基因组学是近期和过去生态系统的关键类群

介绍

哺乳动物拥有大约 6000 种公认的物种,是几乎所有已知生态系统,尤其是所有陆地生物群落的重要分类群(Jones & Safi 2011)。陆地哺乳动物通常通过养分循环、能量流动、授粉、种子传播以及其他自下而上和自上而下的过程对初级生产者产生至关重要的影响(Lacher 等人, 2019 年)。这些功能对初级生产者的社区结构产生了显着影响,这再次影响了初级消费者的社区。然而,当前丰度的迅速下降以及众多哺乳动物物种的灭绝和灭绝引发了保护问题,不仅涉及相关的分类群,还涉及生态系统功能(Lacher et al. 2019)。对陆生哺乳动物的存在、丰度和生态功能进行全面评估需要进行全面监测,最好使用涵盖长时间的数据。特定的哺乳动物群落组合,即分类多样性、相对丰度和遗传多样性,可以成为生态系统功能和生态系统随时间变化的重要指标(Lundgren 等人, 2020 年)。因此,监测目前的哺乳动物种群并了解过去的种群变化是陆地生态系统评估的重要组成部分(Morellet 等人, 2007 年)。

现存的物种组合和相对丰度通常通过直接观察、活体诱捕或相机诱捕来评估。然而,由于大量的后勤工作、需要长时间和空间覆盖以及劳动密集型数据处理,这些方法可能存在问题。此外,在某些情况下,在涉及密切相关(或表型相似)的物种时,通过视觉识别的分类分辨率可能是不够的。这些问题在远离人类基础设施的研究不足的生态系统中被放大。陆生哺乳动物通过粪便、粘液、唾液、气溶胶、毛发、配子、上皮细胞和组织分解等物质不断地将遗传物质释放到它们的环境中。因此,环境 DNA(eDNA;见方框 1) 包含大量无法使用传统方法捕获的信息。目前,eDNA 最常见的应用是检测给定栖息地中特定分类单元的存在(Rees et al. 2014 年,鲁珀特等人。 2019 ); 在这方面,eDNA 允许对物种水平进行准确的分类解析,包括隐秘的种内遗传多样性 (Thomsen & Willerslev 2015 ),这可能揭示未知的生物多样性,甚至可以用于个体识别 (Seeber et al. 2017 )。在某些情况下,基于 eDNA 的调查方法在确定物种存在方面的表现优于传统调查方法(Civade 等人 2016 年,Deiner 等人 2016 年))。在基因组层面,eDNA 可以提供有关野生动物种群的大量信息,这可以提供从个体遗传学到进化适应等各个方面的见解。哺乳动物作为病原体宿主或载体的功能对于人群之间的疾病传播和种间传播特别感兴趣。研究病原体的宿主基因组学和 eDNA 有助于阐明疾病传播模式(Lang & Blanchong 2012 , Dayaram 等人 2021),这对于野生哺乳动物以及野生动物和家畜交界处病原体传播的结论和管理措施可能至关重要.

| 环境 DNA (eDNA) | 从原始活生物体中脱落的环境样品(如水或沉积物)中分离的 DNA,无论是作为细胞外分子还是在细胞隔间内 |

|---|---|

| 古代 DNA (aDNA) | 从古代标本中分离出的 DNA,包括大量样本 |

| 大宗样品 | 可能包括活生物体和 eDNA 的环境材料样本 |

| 条形码 | 使用短的、确定的基因组区域识别物种,例如用于动物的细胞色素 c 氧化酶亚基 1 的片段 |

| 元条形码 | 使用适合此目的的基因组区域序列识别含有来自多个分类单元的 DNA 的样本中的分类单元 |

| 元遗传学 | 使用一种或几种遗传标记对含有来自多个分类单元的 DNA 的样本进行任何遗传分析 |

| 宏基因组学 | 从包含一个以上分类单元的样本中产生全面的基因组数据(或整个基因组中众多标记的数据),即在社区规模上 |

| 古基因组学 | 使用古代 DNA 产生基因组数据 |

关于过去陆生哺乳动物的分布,传统上的研究必须依靠有机体遗骸,通过视觉分析。这些可以是骨头 (van der Plicht et al. 2015 ) 和其他宏观遗骸,例如头发 (Iacumin et al. 2005 ) 或粪化石 (Chin & Kirkland 1998 )。这种哺乳动物存在的直接证据并不总是很容易保存,发现哺乳动物化石遗骸的可能性很低,而且化石记录也不完整。这意味着,例如,一个物种最年轻的化石永远不会代表真正的最后外观——这一原理被称为 Signor-Lipps 效应(Signor & Lipps 1982)。除了直接证据外,古生态学研究还可以利用特定的替代物来检测哺乳动物的存在,特别是粪便真菌(Davies 2019,Goethals & Verschuren 2019)和寄生虫,例如螨虫(Chepstow-Lusty 等, 2019)。

第一项从 eDNA 中鉴定出大型生物的研究针对几种陆地哺乳动物和植物的古代 DNA (aDNA),它们是从西伯利亚永久冻土样本中成功分离出来的 (Willerslev et al. 2003 )。自从这项开创性研究在近 20 年前发表以来,在使用大量水生动物和陆生植物的 eDNA 方面已经取得了相当大的进展,并且研究为过去和当前生态系统的结构和变化提供了宝贵的见解(例如 Deiner 等人。 2017 年,Parducci 等人, 2019 年)。相比之下,尽管有大量潜在的应用和研究问题有待回答,包括生态系统中的生物相互作用、群落随时间的变化、迁徙模式、病原体压力和对变化的进化适应,但很少有研究关注陆地哺乳动物。环境。

在这里,我们回顾了使用来自环境样本的 DNA 的研究,并重点关注作为许多陆地环境的基石类群的陆地哺乳动物。我们综合了采用 eDNA 技术研究陆生哺乳动物时所面临的特定的固有挑战,这解释了哺乳动物 eDNA 研究的相对稀缺性。我们简要介绍了当前的方法学方法,并详细阐述了基于 eDNA 的陆生哺乳动物研究的潜在和剩余挑战的三个方面:1)从不同地点和底物获取陆生哺乳动物的 eDNA;2) 制定哺乳动物物种组合的分类识别策略和估计相对丰度;3) 从 eDNA 中推断出有关哺乳动物的生态生理学和行为以及病原体作用的信息。更远,

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号