Until recently, the processes of litter decomposition and soil organic matter formation in forests have been studied in isolation, which has hindered the development of a comprehensive understanding of the entire process. The last decade has brought considerable progress in this scientific endeavour in response to the challenge to sequester atmospheric C in forest soils. In this paper we review key recent developments in this field and describe our current collective understanding of litter decomposition and transformation processes and pathways in forest ecosystems.

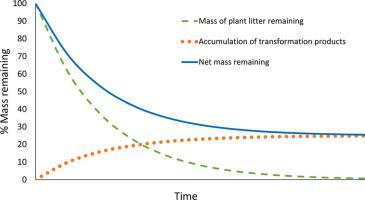

Compelling evidence that most slow-cycling SOM has been microbially transformed forces us to rethink the standard technique of measuring mass remaining in litterbags during incubation to indicate litter decomposition rates. Rather than indicating the mass of litter that remains undecomposed, these measurements reflect the net outcome of two simultaneous processes: decomposition of plant material and accumulation of microbial and faunal transformation products. Measurement of both of these pools, rather than just the total mass of material in litterbags is necessary to understand decomposition processes. For example, the apparent retarding effect of available N on mass loss during late-stage decomposition may actually result from N promoting the production of microbial biomass and necromass, thereby increasing the accumulation of transformation products during late-stage decay. We recommend referring to the mass of material in litterbags as ‘net mass remaining’ or ‘residue mass’ rather than ‘litter mass’, to acknowledge its changing composition as decomposition proceeds.

Decomposition pathways in forests with abundant detritivorous meso- and macrofauna remain poorly understood as a consequence of the inability of the litterbag technique to capture their influences (even with differing mesh sizes). Long-term studies monitoring the transformation of litter to faunal faecal material and subsequent transformations of this material are urgently needed.

Roots and mycorrhizal fungal hyphae are important sources of SOM, including stable SOM. Fine roots (orders 1 and 2) decompose particularly slowly, as do some mycorrhizal hyphae, which has been attributed to cell-wall constituents such as lignins, melanin and glycoproteins. Convergence of mass loss curves of litters that initially decompose quickly and slowly indicates that leaf litter, root litter, and fungal residues with large labile contents can generate as much SOM as recalcitrant litters.

Transformation of litter into SOM can follow many pathways, depending on characteristics of the site. Key site and soil properties influence the biotic community present and together determine the pathway that decomposition follows on that site. As such, litter transformations occur along a continuum between situations in which aboveground litter is mainly transformed into humus that accumulates on the soil surface, and situations in which partially decomposed litter is transferred to the mineral soil via bioturbation. Predicting the most likely decomposition pathway should inform decisions on how to measure and interpret the transformations that occur on a particular site.

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号