Scientific Reports ( IF 3.8 ) Pub Date : 2020-04-03 , DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-62552-4

Philip G Hamill 1 , Andrew Stevenson 1 , Phillip E McMullan 1 , James P Williams 1 , Abiann D R Lewis 1 , Sudharsan S 2 , Kath E Stevenson 3 , Keith D Farnsworth 1 , Galina Khroustalyova 4 , Jon Y Takemoto 5 , John P Quinn 1 , Alexander Rapoport 4 , John E Hallsworth 1

|

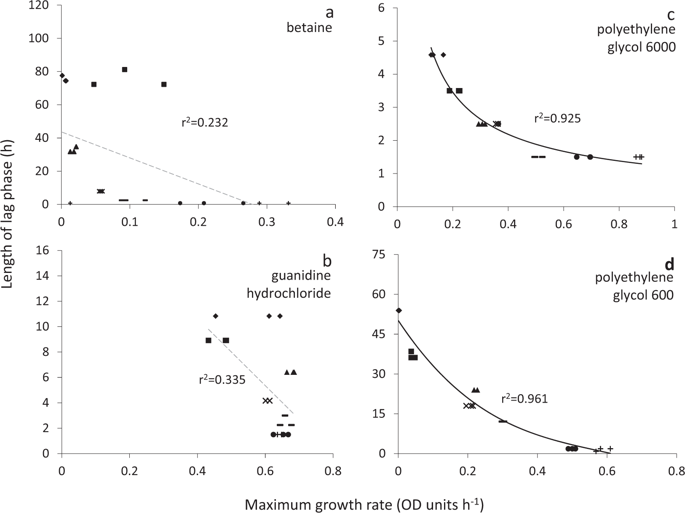

Measures of microbial growth, used as indicators of cellular stress, are sometimes quantified at a single time-point. In reality, these measurements are compound representations of length of lag, exponential growth-rate, and other factors. Here, we investigate whether length of lag phase can act as a proxy for stress, using a number of model systems (Aspergillus penicillioides; Bacillus subtilis; Escherichia coli; Eurotium amstelodami, E. echinulatum, E. halophilicum, and E. repens; Mrakia frigida; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Xerochrysium xerophilum; Xeromyces bisporus) exposed to mechanistically distinct types of cellular stress including low water activity, other solute-induced stresses, and dehydration-rehydration cycles. Lag phase was neither proportional to germination rate for X. bisporus (FRR3443) in glycerol-supplemented media (r2 = 0.012), nor to exponential growth-rates for other microbes. In some cases, growth-rates varied greatly with stressor concentration even when lag remained constant. By contrast, there were strong correlations for B. subtilis in media supplemented with polyethylene-glycol 6000 or 600 (r2 = 0.925 and 0.961), and for other microbial species. We also analysed data from independent studies of food-spoilage fungi under glycerol stress (Aspergillus aculeatinus and A. sclerotiicarbonarius); mesophilic/psychrotolerant bacteria under diverse, solute-induced stresses (Brochothrix thermosphacta, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus); and fungal enzymes under acid-stress (Terfezia claveryi lipoxygenase and Agaricus bisporus tyrosinase). These datasets also exhibited diversity, with some strong- and moderate correlations between length of lag and exponential growth-rates; and sometimes none. In conclusion, lag phase is not a reliable measure of stress because length of lag and growth-rate inhibition are sometimes highly correlated, and sometimes not at all.

中文翻译:

微生物滞后期可以指示细胞应激或独立于细胞应激。

用作细胞应激指标的微生物生长测量有时在单个时间点进行量化。实际上,这些测量结果是滞后长度、指数增长率和其他因素的复合表示。在这里,我们使用许多模型系统(青曲霉、枯草芽孢杆菌、大肠杆菌、 Eurotium amstelodami 、 E. echinulatum 、 E. halophilicum和 E. repens; Mrakia )研究滞后期的长度是否可以作为应激的代理。寒冷酵母( Saccharomyces cerevisiae) ;干燥干金菌(Xerochrysium xerophilum) ;双孢干酵母(Xeromyces bisporus )暴露于机械上不同类型的细胞应激,包括低水活性、其他溶质诱导的应激和脱水-再水合循环。滞后期既不与双孢双孢菌(FRR3443) 在添加甘油的培养基中的发芽率 (r 2 = 0.012) 成正比,也不与其他微生物的指数生长率成正比。在某些情况下,即使滞后保持不变,增长率也会随着压力源浓度的变化而发生很大变化。相比之下,补充有聚乙二醇 6000 或 600 的培养基中的枯草芽孢杆菌(r 2 = 0.925 和 0.961)以及其他微生物物种之间存在很强的相关性。我们还分析了甘油胁迫下食物腐败真菌( Aspergillus aculeatinus和A. 菌核);多种溶质诱导应激下的嗜温/耐冷细菌(热环丝菌、粪肠球菌、荧光假单胞菌、鼠伤寒沙门氏菌、金黄色葡萄球菌);和酸胁迫下的真菌酶( Terfezia claveryi脂氧合酶和双孢蘑菇酪氨酸酶)。这些数据集还表现出多样性,滞后长度和指数增长率之间存在一些强相关性和中度相关性;有时没有。总之,滞后期并不是压力的可靠衡量标准,因为滞后期的长度和生长速率抑制有时高度相关,有时根本不相关。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号