Abstract

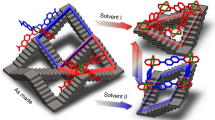

Topological transitions between considerably different phases typically require harsh conditions to collectively break chemical bonds and overcome the stress caused to the original structure by altering its correlated bond environment. In this work we present a case system that can achieve rapid rearrangement of the whole lattice of a metal–organic framework through a domino alteration of the bond connectivity under mild conditions. The system transforms from a disordered metal–organic framework with low porosity to a highly porous and crystalline isomer within 40 s following activation (solvent exchange and desolvation), resulting in a substantial increase in surface area from 725 to 2,749 m2 g–1. Spectroscopic measurements show that this counter-intuitive lattice rearrangement involves a metastable intermediate that results from solvent removal on coordinatively unsaturated metal sites. This disordered–crystalline switch between two topological distinct metal–organic frameworks is shown to be reversible over four cycles through activation and reimmersion in polar solvents.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All relevant data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request. The synthetic procedures, crystallographic, spectroscopic, computational and enzyme catalysis data are provided in the Supplementary Information. The unit-cell parameters and atomic positions were obtained by Rietveld refinement of the PXRD data, using the AlTz-53-DMF, AlTz-53-DEF and AlTz-68 crystal structural models reported in the Article. The X-ray crystallographic data for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition nos. 1892351 (AlTz-53-DEF), 1892352 (AlTz-53-DMF) and 1892353 (AlTz-68). The data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Change history

10 December 2019

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0404-9

References

Dobson, C. M. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature 426, 884–890 (2003).

Fersht, A. R. & Daggett, V. Protein folding and unfolding at atomic resolution. Cell 108, 573–582 (2002).

Auton, M. & Bolen, D. W. Predicting the energetics of osmolyte-induced protein folding/unfolding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15065–15068 (2005).

Farha, O. K. & Hupp, J. T. Rational design, synthesis, purification, and activation of metal–organic framework materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1166–1175 (2010).

Ma, J., Kalenak, A. P., Wong‐Foy, A. G. & Matzger, A. J. Rapid guest exchange and ultra-low surface tension solvents optimize metal–organic framework activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14618–14621 (2017).

Serre, C. et al. Role of solvent–host interactions that lead to very large swelling of hybrid frameworks. Science 315, 1828–1831 (2007).

Serre, C. et al. Very large breathing effect in the first nanoporous chromium(iii)-based solids: MIL-53 or CrIII(OH)·{O2C–C6H4–CO2}·{HO2C–C6H4–CO2H}x·H2Oy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13519–13526 (2002).

Mason, J. A. et al. Methane storage in flexible metal–organic frameworks with intrinsic thermal management. Nature 527, 357–361 (2015).

Schneemann, A. et al. Flexible metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6062–6096 (2014).

Yuan, S. et al. Flexible zirconium metal–organic frameworks as bioinspired switchable catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10776–10780 (2016).

Su, J. et al. Redox-switchable breathing behavior in tetrathiafulvalene-based metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 8, 2008 (2017).

Moghadam, P. Z. et al. Adsorption and molecular siting of CO2, water, and other gases in the superhydrophobic, flexible pores of FMOF-1 from experiment and simulation. Chem. Sci. 8, 3989–4000 (2017).

Fairen-Jimenez, D. et al. Opening the gate: framework flexibility in ZIF-8 explored by experiments and simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8900–8902 (2011).

Knebel, A. et al. Defibrillation of soft porous metal–organic frameworks with electric fields. Science 358, 347–351 (2017).

Morris, R. E. & Brammer, L. Coordination change, lability and hemilability in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 5444–5462 (2017).

Yuan, S. et al. Cooperative cluster metalation and ligand migration in zirconium metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14696–14700 (2015).

Choi, S. B. et al. Reversible interpenetration in a metal–organic framework triggered by ligand removal and addition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8791–8795 (2012).

Allan, P. K., Xiao, B., Teat, S. J., Knight, J. W. & Morris, R. E. In situ single-crystal diffraction studies of the structural transition of metal–organic framework copper 5-sulfoisophthalate, Cu-SIP-3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3605–3611 (2010).

Xiao, B. et al. Chemically blockable transformation and ultraselective low-pressure gas adsorption in a non-porous metal organic framework. Nat. Chem. 1, 289–294 (2009).

Ghosh, S. K., Zhang, J. P. & Kitagawa, S. Reversible topochemical transformation of a soft crystal of a coordination polymer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 7965–7968 (2007).

Smart, P. et al. Zipping and unzipping of a paddlewheel metal–organic framework to enable two‐step synthetic and structural transformation. Chem. Eur. J 19, 3552–3557 (2013).

Guillerm, V. et al. A supermolecular building approach for the design and construction of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6141–6172 (2014).

Whitfield, T. R., Wang, X. Q., Liu, L. M. & Jacobson, A. J. Metal–organic frameworks based on iron oxide octahedral chains connected by benzenedicarboxylate dianions. Solid State Sci. 7, 1096–1103 (2005).

Loiseau, T. et al. A rationale for the large breathing of the porous aluminum terephthalate (MIL-53) upon hydration. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 1373–1382 (2004).

Yang, Q. Y. et al. Probing the adsorption performance of the hybrid porous MIL-68(Al): a synergic combination of experimental and modelling tools. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 10210–10220 (2012).

Bennett, T. D. et al. Hybrid glasses from strong and fragile metal–organic framework liquids. Nat. Commun. 6, 8079 (2015).

Cairns, A. B. & Goodwin, A. L. Structural disorder in molecular framework materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 4881–4893 (2013).

Gaillac, R. et al. Liquid metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 16, 1149–1154 (2017).

Umeyama, D., Horike, S., Inukai, M., Itakura, T. & Kitagawa, S. Reversible solid-to-liquid phase transition of coordination polymer crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 864–870 (2015).

Alvarez, E. et al. The structure of the aluminum fumarate metal–organic framework A520. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3664–3668 (2015).

Jiang, Y. J. et al. Effect of dehydration on the local structure of framework aluminum atoms in mixed linker MIL-53(Al) materials studied by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2886–2890 (2010).

Samanta, S. & Biswas, P. Metal free visible light driven oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl derivatives using 3,6-di(pyridine-2-yl)-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (pytz) as catalyst. RSC Adv 5, 84328–84333 (2015).

Colthup, N., Daly, L. & Wiberley, S. Introduction to Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy 3rd edn (Elsevier, 1990).

Howarth, A. J. et al. Best practices for the synthesis, activation, and characterization of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Mater. 29, 26–39 (2017).

Cliffe, M. J. et al. Correlated defect nanoregions in a metal–organic framework. Nat. Commun. 5, 4176 (2014).

Avci, C. et al. Self-assembly of polyhedral metal–organic framework particles into three-dimensional ordered superstructures. Nat. Chem. 10, 78–84 (2018).

Fan, W. et al. Hierarchical nanofabrication of microporous crystals with ordered mesoporosity. Nat. Mater. 7, 984–991 (2008).

Kao, J. et al. Rapid fabrication of hierarchically structured supramolecular nanocomposite thin films in one minute. Nat. Commun. 5, 4053 (2014).

Carrington, E. J. et al. Solvent-switchable continuous-breathing behaviour in a diamondoid metal–organic framework and its influence on CO2 versus CH4 selectivity. Nat. Chem. 9, 882–889 (2017).

Millange, F., Serre, C., Guillou, N., Ferey, G. & Walton, R. I. Structural effects of solvents on the breathing of metal–organic frameworks: an in situ diffraction study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4100–4105 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to the memory of H.-Y. Huang (Department of Chemistry, Chung Yuan Christian University) for her enthusiasm for—and encouragement of—this work. The gas adsorption–desorption studies and enzyme immobilization of this research were supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (under MOST-106-2113-M-033-001) and Chung Yuan Christian University. Thermogravimetric analysis–mass spectrometry, transmission electron microscopy, and PXRD characterization and analysis were funded by the Robert A. Welch Foundation through a Welch Endowed Chair to H.-C.Z. (A-0030). Solid-state NMR and scanning electron microscopy were supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (under MOST-106-2113-M-007-023-MY2) and the National Tsing Hua University. The material syntheses were funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (under MOST-103-2113-M-001-005-MY3) and Academia Sinica. The spectroscopic characterization and analysis (infrared) work were supported by the US Department of Energy (under award no. DE-FG02-08ER46491, and finished under award no. DE-SC0019902). The authors acknowledge the support with a 01C2 beam line from the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Taiwan. The PDF structural analyses were supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science and Office of Basic Energy Sciences (DOE‐BES) (under contract no. DE-SC0017864), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW) (3DEM-NATUR project no. 2012.0112) and the Swedish Research Council (VR, 2017–04321). S.J.L.B. and S.T. were supported for PDF analysis by the NSF MRSEC programme through Columbia University in the Center for Precision Assembly of Superstratic and Superatomic Solids (DMR-1420634). Use of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, Brookhaven National Laboratory, was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (under contract no. DE-SC0012704). The authors also acknowledge the valuable assistance and discussion from H. Deng and J. Li.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-H.L., S.-L.W., Y.J.C and H.-C.Z. conceived the research idea and designed the experiments. Experiments and data analysis were performed by S.-H.L., L.F., S.Y., C.-C.Y. and W.-L.L. Structure characterization was performed by K.T., Z. H., B.-H.L., G.S.D., S.T., S.J.L.B. and Y.J.C. Density functional theory calculations were performed by K.-Y.W. The manuscript was drafted by L.F., K.T., Y.J.C, T.-T.L., S.-H.L., K.-L.L., Z.H., X.Z. and H.-C.Z. All authors have approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Synthetic procedures, crystallographic, spectroscopic, computational and enzyme catalysis data; Supplementary Figs. 1–47 and Refs. 1–25.

Supplementary Movie 1

Illustration of desolvation-triggered domino-like lattice rearrangement of Al-MOFs.

Crystallographic data

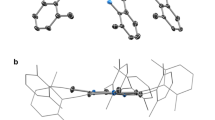

CIF for AlTz-53-DEF; CCDC number: 1892351.

Crystallographic data

CIF for AlTz-53-DMF; CCDC number: 1892352.

Crystallographic data

CIF for AlTz-68; CCDC number: 1892353.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, SH., Feng, L., Tan, K. et al. Rapid desolvation-triggered domino lattice rearrangement in a metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 12, 90–97 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0364-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0364-0

This article is cited by

-

Understanding water reaction pathways to control the hydrolytic reactivity of a Zn metal-organic framework

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Desolvation of metal complexes to construct metal–organic framework glasses

Nature Synthesis (2023)

-

Amorphous NH2-MIL-68 as an efficient electro- and photo-catalyst for CO2 conversion reactions

Nano Research (2023)

-

Defects engineering simultaneously enhances activity and recyclability of MOFs in selective hydrogenation of biomass

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Controlling dynamics in extended molecular frameworks

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2022)