Abstract

Chiral binaphthols (BINOL)-metal combinations serve as powerful catalysts in asymmetric synthesis. Their chiral induction mode, however, typically relies on multifarious non-covalent interactions between the substrate and the BINOL ligand. In this work, we demonstrate that the chiral-at-metal stereoinduction mode could serve as an alternative mechanism for BINOL-metal catalysis, based on mechanistic studies of BINOL-aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones. Theoretical calculations reveal that an octahedral stereogenic-at-metal aluminum alkoxide species is the most stable species within the reaction system, and also is the catalytic relevant intermediate, promoting the stereo-determining hydroboration reaction through a ligand-assisted hydride transfer mechanism rather than the conventional hydroalumination mechanism. These computations reproduce the experimental selectivities and also rationalize the stereoinduction mechanism, which arises from the aluminum-centered chirality induced by chiral BINOL ligands during diastereoselective assembly. The reliability of the proposed mechanism could be verified by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction characterization of the octahedral aluminum alkoxide complex. Additional NMR and Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) experiments elucidated the behavior of the hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide in the solution phase. We anticipate that these findings will extend the applicability of BINOL-metal catalysis to a broader range of reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

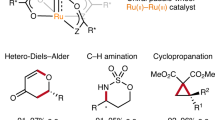

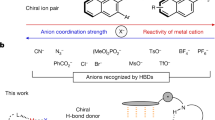

Asymmetric catalysis provides a powerful tool for the precise construction of multi-level chiral functional materials1,2,3. Understanding the chiral induction mechanism is one of the central questions in the area of asymmetric synthesis4,5,6, and it is of great significance for the rational design of catalysts producing improved stereoselectivity and even novel catalytic strategies7,8,9,10. Chiral binaphthols (BINOL)-metal complexes, with their expansive combinatorial possibilities and exceptional chiral control capabilities, have become powerful catalysts in asymmetric synthesis11,12,13,14. Over the past few decades, a wide range of asymmetric reactions have been developed utilizing BINOL-metal combinations. Despite the diverse applications of BINOL ligands, the chiral induction mechanism of these processes mainly relies on non-covalent interactions15,16 between the catalyst microenvironment and the substrates (Fig. 1a).

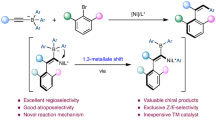

a Schematic representation of BINOL-metal catalysts, basic activation mode and chiral induction mechanism. b Asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones by BINOL-aluminum catalysis and previously proposed aluminum hydride-based mechanism. c Unlocking octahedral chiral-at-metal catalysis mechanism in BINOL-metal catalytic systems with BINOL-aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones as a case of study (This work).

Stereospecific catalytic hydroboration of ketones is one of the most efficient methods to generate chiral alcohols that are fundamental functionalities in pharmaceuticals, natural products, etc17,18. This can be achieved by either transition metal19,20,21 or rare-earth metal catalysis22,23,24. The use of main-group element catalysts for the hydroboration of carbonyl derivatives is highly attractive due to the advantages of economy and environmental sustainability25,26,27,28. In this field, aluminum29,30,31,32, calcium33,34, magnesium35,36, and boron catalysts37 have been reported. Despite these achievements, examples of enantioselective hydroboration of ketones with main-group catalysts are still rare38,39,40,41. Recently, Rueping and coworkers elegantly introduced a BINOL-aluminum catalytic system for the asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones 1 using pinacolborane (HBpin) (Fig. 1b)42. A pathway involving the hydroalumination of C=O bond was proposed for this borylation reaction. It is speculated that the hydroalumination step is the stereo-determining step, with the steric hindrance effect being the source of enantioselectivity (Fig. 1b). It should be mentioned that such a BINOL-aluminum catalytic system is not only applicable to the alkyl-(pyridine-2-yl) methanones but also suitable to aryl-(pyridine-2-yl) methanones, a type of substrate with low discrimination in terms of steric hindrance between the two substituents at the carbonyl carbon atom. This distinctive reaction outcome intrigued us to revisit the rationale of this asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones.

In this work, by employing a combination of quantum chemical calculations and experimental studies on the mechanism of BINOL-aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones, an unusual octahedral chiral-at-aluminum complex43,44,45,46,47, resulting from BINOL ligands-induced diastereoselective assembly, was discovered (Fig. 1c). This aluminum complex is predicted to be thermodynamically more favorable than the previously proposed aluminum hydride complex, being the real catalytically relevant species. The proposed octahedral aluminum alkoxide complex was isolated and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis, NMR and ECD spectra. Additionally, this isolated aluminum species has been proven to reproduce the reactivity of the in situ generated catalyst. With this hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide complex as the key intermediate, a different pathway involving a sequence of ligand-assisted hydride transfer48,49, Al-O/O-B σ-bond metathesis, was proposed. Ligand-assisted hydroboration of octahedral chiral-at-aluminum complex with HBpin is the stereo-determining step. The source of enantioselectivity is the aluminum-centered chirality rather than steric repulsion. The discovered chiral induction mode could account for the observed enantioselectivity of both alkyl-(pyridine-2-yl) methanones and aryl-(pyridine-2-yl) methanones. To the best of our knowledge, this chiral-at-aluminum catalytic mechanism represents a pioneering metal-centered stereoinduction mode in the field of BINOL-metal catalysis.

Results

Theoretical investigations on possible BINOL-Al complex within the catalytic system

Based on previous studies on aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric Meerwein-Schmidt-Ponndorf-Verley reduction of ketones15,50,51,52, we first explored two pathways leading to different catalytically active species: the aluminum hydride (Al-H) and the aluminum alkoxide (Fig. 2a) with B3LYP53,54-D355 calculations. Optimized structures were obtained at Def2-SVP basis set, and single-point calculations were conducted at a large Def2-TZVP basis set. The solvent effect was treated with Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM)56,57 (toluene). Since [(R)-CF3-BINOL-AlMe]2 4-dimer has already been experimentally characterized42, we use 4-dimer as the starting point of the free energy profile and 2-acetylpyridine 1a as the model substrate.

a Reaction pathways for the generation of the aluminum hydride and the hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide (free energies are with respect to 4-dimer in kcal/mol). b Schematic representations of all diastereomers of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides 12 (free energies are with respect to 12c in kcal/mol). Computational details are described in the text. c π-π stacking interaction in 12c identified by the independent gradient model (IGM)60,61. Color codes: H, white; C, yellowish-brown; O, red; N, blue; F, cyan; Al, dusty red.

Figure 2a displays the computed free energy profile for the formation of both the previously reported aluminum hydride species and the discovered hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide complexes. In line with earlier studies by Rueping et al., the formation of the aluminum hydride species follows a sequential process involving methyl migration and Al-O/H-B σ-bond metathesis (Fig. 2a, in gray line)42. This process is exergonic by 22.9 kcal/mol, and the methyl migration step is the rate-limiting step with an activation barrier of 21.9 kcal/mol (via TS-6-7). While this process is kinetically accessible, we unexpectedly observed that for the pentacoordinated intermediate 7, the nitrogen atom of the coordinated 2-acetylpyridine 1a can further bind with the aluminum center, leading to the formation of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides, such as 12c and 12f (Fig. 2a, in blue line). In both 12c and 12f, substrate 1a exhibits a bidentate coordination mode with the aluminum center. The formation of these two species is notably exergonic, with energy releases of 49.5 and 44.2 kcal/mol, respectively. It is worth noting that the previously mentioned aluminum hydride intermediate 10 is predicted to be thermodynamically less favorable than 12c by a substantial margin, with an energy difference of 26.6 kcal/mol. Also, hexcoordinated aluminum alkoxides are more stable than pentacoordinated aluminum alkoxides (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4). It shoud also be mentioned that we also computationally revisited the hydroboration reaction with 2-benzoylpyridine as the model substrate. We found that the aluminum hydride mechanism failed to explain the stereoselectivity when using 2-benzoylpyridine as the model substrate according to the small barrier difference (ΔΔGǂcal = 0.2 kcal/mol), which is in contradiction with the experimentally observed enantioselectivity (98% ee, ΔΔGǂexp > 2.7 kcal/mol) (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results hint that the stereoselective hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones via the aluminum hydride mechanism is unlikely.

Along with 12c and 12f, eight configurations of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides could be located through ligand rearrangement, and all of them possess metal-centered chirality (Fig. 2b)47,58. Among these configurations, 12c is the most stable species. The free energy difference of the second most stable species 12g relative to 12c is as high as 4.5 kcal/mol. To validate the reliability of B3LYP-D3 calculations, we conducted a benchmark study using highly accurate DLPNO-CCSD(T)59 method (Supplementary Table 2). The absolute errors between the B3LYP-D3 and DLPNO-CCSD(T) relative energies are always less than 1.0 kcal/mol, highlighting the reliability of B3LYP-D3 results. This means that BINOL-AlMe reacts with two equivalents of heteroaryl ketone substrates, leading to a chiral-at-metal complex with a definite stereo configuration such as 12c in this system. In this complex, the substrate with bidentate coordination at the metal center is in a well-defined chiral environment, which facilitates the following asymmetric transformation.

Previously, the generation of chiral-at-metal catalysts typically required the use of transition metals or multidentate ligands43,44,45,46,47. This BINOL-induced asymmetric self-assembly provides an alternative route to generate chiral-at-metal complexes. Two factors, π-π stacking60,61 and trans-effect62,63 might be responsible for the unique stability of 12c. Generally, Λ-configured aluminum species feature better π-π stacking interactions than Δ-configurations (Supplementary Fig. 6). As displayed in Fig. 2c, both two side arms of the BINOL ligand in Λ-12c adopt π-π stacking interactions with the coordinated substrates. Besides, the two pyridine groups in 12c adopted in trans-orientation can avoid the trans-effect of the pyridine ligands with strong σ-donors (here are the BINOLate, alkoxide, etc.), which might weaken the coordination of pyridine groups. This trans-effect is supported by the shorter Al-N bond distances in Λ-12c (2.02 Å and 2.06 Å) than the other seven configurations (dAl-N = 2.03 ~ 2.22 Å) (Supplementary Table 1). These two factors can be used to predict the configuration of other chiral-at-metal complexes.

Experimental investigation

Based on the comprehensive investigation of possible BINOL-Al complexes within the catalytic system, we speculated that thermodynamically stable hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides might be experimentally characterized. After extensive screening of the substrate and solvent system, we successfully isolated a hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides species (13g) from the reaction of in situ [(R)-CF3-BINOL-AlMe]2 4-dimer with 2-(4-chlorobenzoyl)pyridine 1c (Fig. 3a).

a Synthetic route and solid-state structure of a hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides species 13g. Color codes: H, white; C, gray; O, red; N, blue; Al, cyan. b Experimental and simulated ECD spectra of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides species 13 in dichloromethane. Gibbs free energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 13c. Computational details are described in the text. c Catalytic performance validation of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides species 13g. For condition B, only the hydroboration of 1h was performed with 2 mol% catalyst loading, and the other substrates were reduced with 1 mol% catalyst loading.

The solid-state structure of 13g revealed an octahedral aluminum center with the substrate 1c bound in a bidentate coordination fashion (Fig. 3a). To investigate other configurational isomers of 13g in the solvent phase, we performed B3LYP-D3 calculations using the basis sets described above. In these calculations, dichloromethane was used as the solvent within the PCM model. Our computational results showed that 13c, 13f, and 13g are more stable than other isomers, and the energy differences of these three structures are within 1.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 3b). The preference for 13g in the solid state could be attributed to the packing effects and/or solubility difference during the crystallization. Dissolving the crystals of 13g in deuterated dichloromethane resulted in a complex mixture according to NMR spectra (Supplementary Figs. 18–20). These results indicate that some configurations of the hexacoordinated aluminum species might coexist and are interconvertible in the solution phase.

To further probe the existing state of the hexacoordinated aluminum species 13g in the solution phase, ECD investigations were performed (Fig. 3b). The ECD spectrum of the isolated crystals in the dichloromethane solution shows a negative Cotton effect at 238 nm, and a positive Cotton effect at 256 nm and 277 nm (Fig. 3b, black solid line). According to our theoretical calculations, configurations 13c, 13f and 13g are the main components in dichloromethane. The simulated ECD spectrum at TD-B3LYP-D3/Def2-TZVP level (with the PCM model, DCM as the solvent) of 13c (Fig. 3b, red dashed line) shows a negative Cotton effect at 245 nm and a positive Cotton effect at 277 nm and 313 nm, which are qualitatively in accord with experimental results. However, configurations 13f and 13g (crystalized configuration) do not contribute to the negative Cotton effect observed at 238 nm but contribute to the positive Cotton effect in the spectrum. We therefore speculated that 13g in the solid state mainly converts into 13c in dichloromethane solution. The NMR and ECD experiments demonstrated the substitutional and configurational lability of the BINOL-aluminum complex, which is different from other chiral-at-metal catalysts with configurational inertness.

Subsequently, we investigated the catalytic activity of 13g using various substrates. As shown in Fig. 3c, both methyl and phenyl substituted substrates 1a and 1b reacted with HBpin in the presence of 1 mol% of 13g with excellent yields and enantioselectivities. 13g reproduced the reactivity of the in situ generated catalyst42. We further validated the catalytic performance of both the in situ generated catalyst and isolated species 13g using heteroaryl ketones bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups (Fig. 3c). Our results show that the in situ generated catalyst provided excellent enantioselectivity (97%-98% ee) for heteroaryl ketones 1d and 1f bearing electron-donating groups (OMe) and 1g bearing an electron-withdrawing group (CF3) on the pyridine ring (Condition A). For 1e, substrate bearing a trifluoromethyl group on the phenyl ring, a slightly lower enantioselectivity (3e, 87% ee) was observed when using the in situ generated catalyst. When using the isolated aluminum species 13g as the catalyst, excellent enantioselectivity can be observed for all four species (Condition B, 98%-99% ee). Notably, for species 1e, complex 13g was able to improve the enantioselectivity (ee value) to 98%, surpassing the results obtained under standard condition (Condition A, 87% ee). Subsequently, for cyclic ketone species 1h, a lower 86% ee value was reported42 using the in situ generated catalyst. Our results show that employing 2 mol% of isolated 13g as catalyst leads to a significantly enhanced ee value (96%). These results indicated that this catalytic system is insensitive to electronic effects, and the octahedral chiral-at-aluminum complex might be the actual catalyst for the asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones. The slightly worse performance observed with the in situ generated catalyst may be attributed to the formation of other unidentified aluminum species during the reaction64,65. Besides, we also found that neither the in situ generated [(R)-CF3-BINOL-AlMe]2 complex nor the isolated aluminum species 13g could effectively catalyze the asymmetric hydroboration of acetophenone (Supplementary Fig. 34). Our results demonstrated that the bidentate coordination of 2-pyridyl ketones with the Al center is essential for achieving high enantioselectivity in hydroboration.

Computed hydroboration pathway with octahedral chiral-at-aluminum as the key intermediate

Based on the computational and experimental results, we proposed that hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides are the resting state of the catalytical species, and then explored free energy profile for the full catalytic cycle of the hydroboration reaction. The intermediates and transition states were located with the help of combined molecular dynamics and coordinate driving method (MD/CD)66,67. Hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides 12 have amphiphilic structural characteristics, in which the alkoxy anion is nucleophilic and the carbonyl group is electrophilic. Many previous studies proposed ligand-assisted hydroboration48,49 as a crucial step in hydroboration of ketones. Thus, we envisioned that when the boron atom of HBpin coordinates with the nucleophilic alkoxy anion, the nucleophilicity of hydride will be enhanced, facilitating the hydride transfer to the electrophilic carbonyl group. According to our assumption, only when the Al-alkoxy bond and carbonyl group of 12 adopted a non-planar configuration (c.f., Fig. 2b, 12a-12d), the related ligand-assisted hydroboration process could occur (Supplementary Fig. 7). Because the configuration of 12a-12d is specific, these hydride transfer events are stereospecific. More specifically, hydride transfer through 12a or 12d could only lead to (S)-enantiomers, while hydride transfer through 12b or 12c lead to (R)-enantiomers.

Due to the fact that 12c and 12d lead to the most favorable transition states for the (R) and (S) products, respectively, only the pathways starting from 12c and 12d are presented in Fig. 4a for simplicity. With the assistance of the alkoxy anion ligand, 12c undergoes a facile hydride transfer from the Bpin group to the carbonyl group, affording the R-configured 14c with an activation barrier of 12.9 kcal/mol (via TS-12c-14c). From 14c, a two-stage Al-O/O-B σ-bond metathesis yields the Al-hydroboration product complex 16c via a transfer of the Bpin group. During the first stage, a B-O bond is formed between the Bpin group and the alkoxy anion ligand in 14c (via TS-14c-15c), resulting in an Al-O-B-O four-membered ring intermediate 15c. Then, 15c undergoes the dissociation of the old B-O bond (via TS-15c-16c), forming the complex 16c. Finally, 16c releases the hydroboration product (R)-2a and regenerates aluminum complex 12c through ligand exchange. Aluminum species 12d is responsible for the formation of the S-configured product and the key hydride transfer process requires an activation barrier of 21.2 kcal/mol via TS-12d-15d. It is worth mentioning that although the absolute configurations of the chiral aluminum center in 12c and 12d are both Λ, the exposed prochiral surfaces of bidentate coordinated substrates in these two configurations are opposite, so they will yield products with opposite configurations. The barrier difference between TS-12c-14c and TS-12d-15d is predicted to be 8.4 kcal/mol using B3LYP-D3 method. We have also calculated the free energy barriers for four different transition states starting from 12a–12d using highly accurate DLPNO-CCSD(T) method. The absolute errors between the B3LYP-D3 and DLPNO-CCSD(T) free energy barriers are always less than 1.0 kcal/mol (Supplementary Table 3). For the barrier difference between TS-12c-14c and TS-12d-15d, the DLPNO-CCSD(T) method predicted a value of 8.3 kcal/mol, which is close to the B3LYP-D3 result. The calculated ∆∆Gǂ values are in qualitative consistency with the experimentally observed enantioselectivity (99% ee).

a Free energy profile for the hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides 12c/12d (with α,α-dimethyl-2-pyridyl alkoxide as one of the ligands) catalyzed hydroboration. b Free energy profile for the 17c/17d (with α-methyl-2-pyridyl alkoxide as one of the ligands) catalyzed hydroboration. Gibbs free energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 12c or 17c. Computational details are described in the text.

Besides regenerating catalytically active species through Al-O/O-B σ-bond metathesis and then ligand exchange, 14c can directly undergo ligand exchange with substrate 1a to give the hexacoordinated aluminum species with similar catalytic activity, such as 17c and 17d (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). As shown in Fig. 4b, as a species like 12c, intermediate 17c can also undergo ligand-assisted hydroboration reaction with HBpin affording (R)-configurated product, with a lower activation barrier (via TS-17c-18c, ΔGǂ = 10.9 kcal/mol). The reaction of 17d with HBpin generates (S)-configurated product just like 12d. Given the similar coordination geometry, the activation barrier difference in the stereo-determining step for the hydroboration with 17c/17d (ΔΔGǂ = 8.0 kcal/mol) is close to that of 12c and 12d (ΔΔGǂ = 8.4 kcal/mol).

The hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides-based mechanism successfully explained the enantioselectivity with 1a as the substrate in the preceding section. We then investigated whether this mechanism can also account for the asymmetric hydroboration of diaryl substrates. With 2-benzoylpyridine 1b as the substrate, similar hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides species (20a–20h, 23a–23h) and their hydride transfer transition states have also been computationally located (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 10–13). Similarly, species 20c and 23c are the most stable configurations among all the configurations considered. Starting from 20c or 23c, the formation of the major R-enantiomer is energetically more favorable with activation barriers of 13.3 kcal/mol (via TS-20c-21c) and 10.7 kcal/mol (via TS-23c-24c). The pathway to yield the S-enantiomer involves much higher barriers (23.5 kcal/mol via TS-20d-22d, or 18.7 kcal/mol via TS-23d-25d), respectively. Unlike the originally proposed Al-H mechanism, the hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides-based mechanism can account for the experimentally observed enantioselectivity (99% ee) for diaryl substrates.

Gibbs free energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 20c and 23c. Computational details are described in the text. Hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides 23c and 23d with a secondary alkoxy ligand are generated through ligand exchange (see Supplementary Fig. 13 for ligand exchange step).

Theoretical investigation on the asymmetric induction mechanism

With the favored activation mode established, we then investigated the factors affecting the enantioselectivity. We decomposed the free energy barrier difference (ΔΔGRelǂ) of the stereo-determining step into the contributions of stability difference of the related hexacoordinated aluminum intermediates (ΔΔGInt) and intrinsic energy difference of the related transition states (ΔΔGIntriǂ = ΔΔGRelǂ–ΔΔGInt, Fig. 6a). Interestingly, ΔΔGInt contributes more than a half to the free energy barrier difference. This means that the source of enantioselectivity is largely a preference for the arrangement of different coordination species at the aluminum center. In addition, ΔΔGIntriǂ also contributes to the free energy barrier difference in the stereo-determining step. For TS-12c-14c related to the formation of major R-enantiomer, this six-membered transition state adopts a chair conformation (Fig. 6b). In contrast, TS-12d-15d adopts a boat-like geometry. This conformational difference was proposed to be responsible for the calculated ΔΔGIntriǂ.

a Contributions of free energy barrier difference (ΔΔGRelǂ) in the stereo-determining step and the experimental ee values with isolated species 13g as the catalyst. Gibbs free energies are in kcal/mol with respect to 12c, 17c, 20c and 23c. Computational details are described in the text. b Structural characteristics of the key hydride transfer transition states TS-12c-14c and TS-12d-15d. Distances are in angstroms (Å). Color codes: H, white; B, pink; C, gray; O, red; N, blue; Al, dusty pink.

Previously, the steric hindrance between the side arms of BINOL ligands and the substrates was proposed to be vital for stereoinduction15,42. However, in the current favored reaction mode, the substrates are arranged in parallel with the side arms of BINOL, resulting in little steric hindrance effect. The observed enantioselectivity is determined by the aluminum-centered chirality resulting from the assembly mode of the substrates around the aluminum center. Accordingly, the chirality transfer mechanism is from chiral ligand to aluminum-centered chirality, and then to the final hydroboration product. For this reason, this reaction mode can account for the enantioselectivity observed with diaryl 2-benzoylpyridine 1b as the substrate, a case for which the Al-H based mechanism was unable to explain the results.

Based on our computational and experimental studies, we proposed an octahedral aluminum-based mechanism for the BINOL-aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones (Fig. 7). The diastereoselective assembly of in situ generated [(R)-CF3-BINOL-AlMe]2 species with two equivalents of substrates yields hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide that is the catalytically relevant species I. In the solution phase, I is in coexistence with some other hexacoordinated aluminum complexes. Subsequently, species I undergoes stereo-determining ligand-assisted hydride transfer to generate the hydroalumination intermediate II. The aluminum-centered chirality induced by the chiral BINOL ligand leads to the experimentally observed enantioselectivity. II can undergo Al-O/O-B σ-bond metathesis, leading to III. The subsequent ligand exchange regenerates the hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxide I and liberates the desired product. Besides, intermediate II can also directly undergo ligand exchange with another substrate molecule to regenerate the related hexacoordinated aluminum complex I and liberate the chiral hydroboration product. The alkoxy anionic ligand plays an important role in the catalytic cycle. First, the complexation of the anionic ligand with the Bpin group enhances the nucleophilic attack of the hydride on the carbon atom of the carbonyl group. In addition, the anionic ligand acts as a relay for the transfer of the Bpin group to the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group in the Al-O/O-B σ-bond metathesis step.

Discussion

In summary, we have identified an octahedral chiral-at-aluminum catalysis mechanism in BINOL-aluminum-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones. BINOL-induced diastereoselective assembly leads to the catalytically active hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides and determines the absolute configuration of the product. The predicted hexacoordinated aluminum complex was successfully isolated and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Further experiments identified the catalytic reactivity of this discovered aluminum complex. This work demonstrated that the combination of main-group metals and simple BINOL ligands can be assembled into chiral-at-metal complexes in the presence of bidentate substrates. In these complexes, the substrates might be activated through a LUMO activation mode3,68 and the alkoxy anionic ligand could be noninnocent, as discussed in the preceding section. We expect our present work to stimulate the future development of asymmetric catalysis using main-group aluminum catalysts, as well as the design of other asymmetric reactions based on the BINOL/metal combination.

Methods

Computational methods

All density functional calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 package (Revision A.03)69. Geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency analysis were performed at B3LYP53,54-D355/Def2-SVP level. The solvent effect was dealed with polarizable continuum model (PCM)56,57 in toluene or dichloromethane. The Def2-TZVP basis set was used to get more accurate single-point energies for all structures with the same functional and implicit solvent model. To simulate ECD spectra, TD-DFT calculations with 100 considered excited state were carried out at B3LYP-D3/Def2-TZVP level with the PCM model to deal with the solvent effect of dichloromethane. DLPNO-CCSD(T)59 calculations with Def2-TZVP basis set were performed with ORCA 5.070 software.

Procedure for the synthesis of hexacoordinated aluminum alkoxides 13g

Inside a glovebox under argon atmosphere, to a solution of (R)-CF3-BINOL (284.2 mg, 0.4 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.6 mL), AlMe3 (0.4 mmol, 200 μL, 2 M in toluene) was dropwise added. After the gas stopped releasing, the reaction solution was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The in situ generated [(R)-CF3-BINOL-AlMe]2 was dropwise added to a solution of (4-chlorophenyl)(pyridin-2-yl)methanone 1c (174.1 mg, 0.8 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.6 mL). The reaction solution was then stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Through a filter membrane, the reaction solution was equally filtered into four small test tubes (inner diameter 6 mm, length 20 cm). To each small test tube, 0.1 mL of dichloromethane was added as a buffer layer. Then each small test tube was layered with at least 1.3 mL of pentane as poor solvent. Finally, the test tubes were tightly sealed. After standing for two weeks, red block crystals of 13g grew on the test tube wall as the sole solids. The mother liquor was decanted off and the solid was washed with cold pentane, affording the product in a yield of 31% (147 mg).

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, and also available from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray crystallographic structures data generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) database under accession code 2288118, 2288119, and 2309175, and can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk. The xyz coordinates of the optimized structures in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yoon, T. P. & Jacobsen, E. N. Privileged chiral catalysts. Science 299, 1691–1693 (2003).

Zhou, Q.-L. Privileged chiral ligands and catalysts. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim; 2011).

Liu, X., Zheng, H., Xia, Y., Lin, L. & Feng, X. Asymmetric cycloaddition and cyclization reactions catalyzed by chiral N,N′-dioxide–metal complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2621–2631 (2017).

Yamakawa, M., Ito, H. & Noyori, R. The metal−ligand bifunctional catalysis: a theoretical study on the ruthenium(ii)-catalyzed hydrogen transfer between alcohols and carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 1466–1478 (2000).

Allemann, C., Gordillo, R., Clemente, F. R., Cheong, P. H.-Y. & Houk, K. N. Theory of asymmetric organocatalysis of aldol and related reactions: rationalizations and predictions. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 558–569 (2004).

Taylor, M. S. & Jacobsen, E. N. Asymmetric catalysis by chiral hydrogen-bond donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 1520–1543 (2006).

Mitsumori, S. et al. Direct asymmetric anti-mannich-type reactions catalyzed by a designed amino acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1040–1041 (2006).

Houk, K. N. & Cheong, P. H.-Y. Computational prediction of small-molecule catalysts. Nature 455, 309–313 (2008).

Wheeler, S. E., Seguin, T. J., Guan, Y. & Doney, A. C. Noncovalent interactions in organocatalysis and the prospect of computational catalyst design. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1061–1069 (2016).

Poree, C. & Schoenebeck, F. A holy grail in chemistry: computational catalyst design: feasible or fiction? Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 605–608 (2017).

Chen, Y., Yekta, S. & Yudin, A. K. Modified BINOL ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 103, 3155–3212 (2003).

Brunel, J. M. BINOL: a versatile chiral reagent. Chem. Rev. 105, 857–898 (2005).

Shibasaki, M. & Matsunaga, S. Design and application of linked-BINOL chiral ligands in bifunctional asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 269–279 (2006).

Pu, L. Asymmetric functional organozinc additions to aldehydes catalyzed by 1,1′-Bi-2-naphthols (BINOLs). Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1523–1535 (2014).

Cohen, R., Graves, C. R., Nguyen, S. T., Martin, J. M. L. & Ratner, M. A. The mechanism of aluminum-catalyzed Meerwein−Schmidt−Ponndorf−Verley reduction of carbonyls to alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 14796–14803 (2004).

Hamashima, Y., Sawada, D., Kanai, M. & Shibasaki, M. A new bifunctional asymmetric catalysis: an efficient catalytic asymmetric cyanosilylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 2641–2642 (1999).

Cho, B. T. Recent development and improvement for boron hydride-based catalytic asymmetric reduction of unsymmetrical ketones. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 443–452 (2009).

Wang, R. & Park, S. Recent advances in metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of ketones. ChemCatChem 13, 1898–1919 (2021).

Guo, J., Chen, J. & Lu, Z. Cobalt-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of aryl ketones with pinacolborane. Chem. Commun. 51, 5725–5727 (2015).

Chen, F., Zhang, Y., Yu, L. & Zhu, S. Enantioselective NiH/pmrox-catalyzed 1,2-reduction of α,β-unsaturated ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 2022–2025 (2017).

Vasilenko, V., Blasius, C. K., Wadepohl, H. & Gade, L. H. Mechanism-based enantiodivergence in manganese reduction catalysis: a chiral pincer complex for the highly enantioselective hydroboration of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8393–8397 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Tris(cyclopentadienyl)lanthanide complexes as catalysts for hydroboration reaction toward aldehydes and ketones. Org. Lett. 19, 3382–3385 (2017).

Song, P., Lu, C., Fei, Z., Zhao, B. & Yao, Y. Enantioselective reduction of ketones catalyzed by rare-earth metals complexed with phenoxy modified chiral prolinols. J. Org. Chem. 83, 6093–6100 (2018).

Sun, Y., Lu, C., Zhao, B. & Xue, M. Enantioselective hydroboration of ketones catalyzed by rare-earth metal complexes containing trost ligands. J. Org. Chem. 85, 10504–10513 (2020).

Power, P. P. Main-group elements as transition metals. Nature 463, 171–177 (2010).

Stephan, D. W. & Erker, G. Frustrated lewis pairs: metal-free hydrogen activation and more. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 46–76 (2010).

Egorova, K. S. & Ananikov, V. P. Which metals are green for catalysis? Comparison of the toxicities of Ni, Cu, Fe, Pd, Pt, Rh, and Au salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12150–12162 (2016).

Wilkins, L. C. & Melen, R. L. Enantioselective main group catalysis: modern catalysts for organic transformations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 324, 123–139 (2016).

Yang, Z. et al. An aluminum hydride that functions like a transition-metal catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10225–10229 (2015).

Jakhar, V. K., Barman, M. K. & Nembenna, S. Aluminum monohydride catalyzed selective hydroboration of carbonyl compounds. Org. Lett. 18, 4710–4713 (2016).

Pollard, V. A. et al. Lithium diamidodihydridoaluminates: bimetallic cooperativity in catalytic hydroboration and metallation applications. Chem. Commun. 54, 1233–1236 (2018).

Bismuto, A., Cowley, M. J. & Thomas, S. P. Aluminum-catalyzed hydroboration of alkenes. ACS Catal. 8, 2001–2005 (2018).

Yadav, S., Pahar, S. & Sen, S. S. Benz-amidinato calcium iodide catalyzed aldehyde and ketone hydroboration with unprecedented functional group tolerance. Chem. Commun. 53, 4562–4564 (2017).

Jin, D., Sun, X. & Roesky, P. W. Heavy alkaline–earth metal formazanate complexes and their catalytic applications. Organometallics 42, 1725–1731 (2023).

Arrowsmith, M., Hadlington, T. J., Hill, M. S. & Kociok-Köhn, G. Magnesium-catalysed hydroboration of aldehydes and ketones. Chem. Commun. 48, 4567–4569 (2012).

Jang, Y. K., Magre, M. & Rueping, M. Chemoselective luche-type reduction of α,β-unsaturated ketones by magnesium catalysis. Org. Lett. 21, 8349–8352 (2019).

Lawson, J. R., Wilkins, L. C. & Melen, R. L. Tris(2,4,6-trifluorophenyl)borane: an efficient hydroboration catalyst. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 10997–11000 (2017).

Corey, E. J. & Helal, C. J. Reduction of carbonyl compounds with chiral oxazaborolidine catalysts: a new paradigm for enantioselective catalysis and a powerful new synthetic method. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 1986–2012 (1998).

Falconnet, A., Magre, M., Maity, B., Cavallo, L. & Rueping, M. Asymmetric magnesium-catalyzed hydroboration by metal-ligand cooperative catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17567–17571 (2019).

Titze, M., Heitkämper, J., Junge, T., Kästner, J. & Peters, R. Highly active cooperative lewis acid—ammonium salt catalyst for the enantioselective hydroboration of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5544–5553 (2021).

Nicholson, K. et al. A boron–oxygen transborylation strategy for a catalytic midland reduction. ACS Catal. 11, 2034–2040 (2021).

Lebedev, Y. et al. Asymmetric hydroboration of heteroaryl ketones by aluminum catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19415–19423 (2019).

Chavarot, M. et al. Chiral-at-Metal” octahedral ruthenium(II) complexes with achiral ligands: a new type of enantioselective catalyst. Inorg. Chem. 42, 4810–4816 (2003).

Belokon, Y. N. et al. Asymmetric synthesis of cyanohydrins catalysed by a potassium Δ-bis[N-salicylidene-(R)-tryptophanato]cobaltate complex. Mendeleev Commun. 14, 249–250 (2004).

Abell, J. P. & Yamamoto, H. Development and applications of tethered bis(8-quinolinolato) metal complexes (TBOxM). Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 61–69 (2010).

Chen, L.-A. et al. Chiral-at-metal octahedral iridium catalyst for the asymmetric construction of an all-carbon quaternary stereocenter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 14021–14025 (2013).

Cruchter, T. & Larionov, V. A. Asymmetric catalysis with octahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes featuring chiral ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 376, 95–113 (2018).

Vasilenko, V., Blasius, C. K. & Gade, L. H. One-pot sequential kinetic profiling of a highly reactive manganese catalyst for ketone hydroboration: leveraging σ-bond metathesis via alkoxide exchange steps. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9244–9254 (2018).

Rothbaum, J. O., Motta, A., Kratish, Y. & Marks, T. J. Mechanistic study of homoleptic trisamidolanthanide-catalyzed aldehyde and ketone hydroboration. Chemically non-innocent ligand participation. Chem. Sci. 14, 3247–3256 (2023).

Campbell, E. J., Zhou, H. & Nguyen, S. T. The asymmetric Meerwein–Schmidt–Ponndorf–Verley reduction of prochiral ketones with iPrOH catalyzed by Al catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 1020–1022 (2002).

Graves, C. R., Zhou, H., Stern, C. L. & Nguyen, S. T. A mechanistic investigation of the asymmetric Meerwein−Schmidt−Ponndorf−Verley Reduction Catalyzed by BINOL/AlMe3 structure, kinetics, and enantioselectivity. J. Org. Chem. 72, 9121–9133 (2007).

Zheng, L. et al. Asymmetric catalytic Meerwein–Ponndorf–verley reduction of ketones with aluminum(III)-VANOL catalysts. ACS Catal 10, 7188–7194 (2020).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104–154122 (2010).

Scalmani, G. & Frisch, M. J. Continuous surface charge polarizable continuum models of solvation. I. General formalism. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 114110–114124 (2010).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Zhang, L. & Meggers, E. Steering asymmetric lewis acid catalysis exclusively with octahedral metal-centered chirality. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 320–330 (2017).

Guo, Y. et al. Communication: an improved linear scaling perturbative triples correction for the domain based local pair-natural orbital based singles and doubles coupled cluster method DLPNO-CCSD(T). J. Chem. Phys. 148, 11101–11105 (2018).

Lefebvre, C. et al. Accurately extracting the signature of intermolecular interactions present in the NCI plot of the reduced density gradient versus electron density. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 17928–17936 (2017).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Quagliano, J. V. & Schubert, L. E. O. The trans effect in complex inorganic compounds. Chem. Rev. 50, 201–260 (1952).

Hartley, F. R. The cis- and trans-effects of ligands. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2, 163–179 (1973).

Son, A. J. R., Thorn, M. G., Fanwick, P. E. & Rothwell, I. P. Isolation and chemistry of aluminum compounds containing (S)-3,3‘-Bis(triphenylsilyl)-1,1‘-bi-2,2‘-naphthoxide ligands. Organometallics 22, 2318–2324 (2003).

Ooi, T., Ichikawa, H. & Maruoka, K. Practical approach to the Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley reduction of carbonyl substrates with new aluminum catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 3610–3612 (2001).

Yang, M., Zou, J., Wang, G. & Li, S. Automatic reaction pathway search via combined molecular dynamics and coordinate driving method. J. Phys. Chem. A 121, 1351–1361 (2017).

Li, G. et al. Combined molecular dynamics and coordinate driving method for automatically searching complicated reaction pathways. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 23696–23707 (2023).

Houk, K. N. Frontier molecular orbital theory of cycloaddition reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 8, 361–369 (1975).

Frisch, M.J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. A.03. (Wallingford, CT; 2016).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system—version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22073043 from S.H.L., and 22273035 from G.Q.W.), the New Cornerstone Science Foundation (S.H.L.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 020514380295, G.Q.W.), and Graduate Student Scientific Research Innovation Projects in Jiangsu Province (No. KYCX23_0111, Z.X.L.). We thank Dr. Jia Cao and Dr. Hui Chen for their insightful discussions. We acknowledge Prof. Juli Jiang for her help on ECD experiments. We acknowledge Prof. Xu Cheng and Prof. Wenhua Zheng for their help on HPLC experiments. We thank Prof. Jianjun Feng for his help on the experiments. All theoretical calculations were performed at the High-Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of Nanjing University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X.L., G.Q.W. and S.H.L conceived the work and designed the computational and experimental investigations. Z.X.L. performed the DFT calculations. Z.G.N. analyzed the non-covalent interactions and performed the DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations. Z.X.L., P.F.C., L.Z.G. and C.Q.Z. conducted the isolation of catalytically active species. Y.Z. analyzed the single crystal structures. R.R.W performed the ECD experiments. Z.X.L. conducted catalytic performance validation of the isolated aluminum species. Z.X.L. and G.Q.W. co-wrote the manuscript with the input from all the other authors. G.Q.W. and S.H.L. directed the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaoli Ma and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Chen, P., Ni, Z. et al. An unusual chiral-at-metal mechanism for BINOL-metal asymmetric catalysis. Nat Commun 16, 735 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56000-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56000-y